Volume 12, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025, 12(4): 271-283 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yadav K, Kumar M, Pathera A. Impact of Storage Conditions on the Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Essential Oils Extracted from Kinnow Peel. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025; 12 (4) :271-283

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1253-en.html

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1253-en.html

Department of Food Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, India , Kavitayadav492@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 1031 kb]

(55 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (93 Views)

Full-Text: (7 Views)

Impact of Storage Conditions on the Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Essential Oils Extracted from Kinnow Peel

K. Yadav 1[*]* , M. Kumar 1, A. Pathera 2

1. Department of Food Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, India

2. Amity Institute of Food Technology, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India

HIGHLIGHTS

-Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation (MAHD)

MAHD was conducted using a household microwave oven (IFB 20PG4S, IFB, India). The power source had a maximum output power of 800 W and a frequency of 2450 MHz. In a 1000 ml beaker, 700 ml of distilled water were used to dissolve 100 g of powdered dried kinnow peel. The flask was placed in the 400 W microwave (IFB 20PG4S, IFB, India) oven for 20 min. The solution was moved into the conical flask and HD was carried out after the microwave treatment (Yu et al., 2021).

-Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation (UAHD)

UAHD was carried out using an Ultrasonic Probe Sonicator (Biogene, India, BGS-185B, 750 W). A mixture of 100 g dried kinnow peel powder and 700 ml distilled water was prepared in a 1000 ml beaker. The ultrasonic probe was applied with a two-second pulse at 225 W for 20 min. After ultrasonication, the treated solution was transferred to a conical flask for HD (Yu et al., 2021).

-Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation (OHHD)

OHHD was carried out utilizing a specifically built device with platinum electrodes developed at the Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology's Food Technology Department. In the ohmic heating assembly, 100 g of dried peel powder were dissolved in 700 ml of distilled water while maintaining the ohmic heating temperature (70 °C), voltage (220 V), and salt (NaCl) concentration (2%). Following the ohmic heating treatment, the procedure's steps were quite similar to those of the HD process. Throughout the procedure, temperature, voltage, and salt content were carefully monitored (Al-Hilphy et al., 2022; Kristinawati et al., 2020).

EO storage conditions

To investigate the impact of different storage conditions on the chemical compositions of distilled oils, oil samples were kept in freezers (−10 °C) and refrigerators (4 °C) for 12 months in dark amber-colored bottles before the analysis. The oil analysis was analyzed over a one-year period for all storage treatments. Freshly extracted oil was also analyzed immediately to establish a baseline, thereby isolating the specific effects of storage conditions on the EO composition. The extracted Eos were light yellowish with a pungent odour.

Compound identification

-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopyanalysis (FTIR)

The EOs of kinnow fruit peel was analyzed using a Fourier transmission infrared spectrophotometer (Spectrum Two, PerkinElmer, USA). The KBr powder (Fisher Scientific, USA) was homogeneously pulverized in a crystal pestle and mortar. The fine powder was subsequently compressed into a homogeneous, thin particle using a hydraulic pellet press (Eagle Press and Equipment Co., Ltd., Canada). The EOs sample was directly placed on the surface of a pair of rectangular sodium chloride plates at room temperature, and measurements were taken in the IR region at 4000-400 cm-1. Two surveys were conducted at a speed of 3 cm/s for each EO, with an air spectrum serving as a reference. The FTIR study was carried out at GJUS&T Hisar Central Instrumentation Laboratory (Sandhu et al., 2021).

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis (GC-MS)

The extracted EOs were evaluated using a GC-MS equipment from Thermo Fisher Scientific in the USA. The instrument featured a GC-Trace 1300, MS-TQS Duo, and Autosampler-TriPlus RSH, connected with a DB-5MS column (length of 40 m, inner diameter of 0.15µm, and film thickness of 0.15µm). For sample preparation, 20 ul of material was dissolved in methanol and the volume was increased to 1 ml using the same solvent, as reported by Van et al. (2022) with minor modifications. Then, 1 ml of EO was injected into the GC-Trace 1300, MS-TQS Duo, and Autosampler-TriPlus RSH, all connected to a DB-5MS column. The fore line pressure temperature was set to 210 oC, the transfer line temperature was 200 oC, and the ionization mode was Electron Impact (EI) at 70 eV. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with an injection volume of 1 µl and an injector temperature of 200 oC. Temperatures varied from 50 oC (held for 5 min) to 210 oC (held for 15 min) during the GC analysis, using a 5 oC/min ramp rate. The mass range for analyte characterization was adjusted to 45–450 (m/z).

The obtained results were compiled by comparing the spectra with the inbuilt National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library, facilitating the identification of components present in the EOs.

Antibacterial activity assay

Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus as well as Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa were used as test organisms to determine antibacterial activity. The bacterial strains were obtained from the Departments of Bio Nano Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. Antibacterial activity was measured as the Zone of Inhibition (ZOI) using the well diffusion method (Anwar et al., 2023).First, 100 ul of the culture suspension was shifted to a petri dish containing Nutrient Agar medium. Then, a 7 mm diameter borer was used to form a well in the agar plate and fill it with EO solution in methanol (400µl/ml). Streptomycin (standard solution) 50 mg was dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water and placed into wells (20µl/well) and methanol (control). The dishes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The antibacterial activity was determined through determining the diameter of the bacterial ZOI in millimeters.

Antifungal activity

Two fungal strains Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans were tested to determine the antifungal activities of kinnow peel EO which was extracted by different methods. The bacterial strains were obtained from the Departments of Bio Nano Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. Active cultures were created by transferring a loopful of cells from stock cultures to flasks containing potato dextrose broth and incubated at 24 oC for 48 h.

First, 100 ul of the fungal suspension was spread on pert dish containing Potato Dextrose Agar medium. A well was then created in the agar plate with a7mm borer and filled the well with EO solution in methanol (400 ul/ml) with 20ul in each well. Fluconazole was diluted in 100 ml distilled water and placed into wells (20 ul/well) and methanol solution, which served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Plates were then incubated at 25 oC for four days. The antibacterial activity was determined by measuring the fungal ZOI diameter in millimeters (Van et al., 2022).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was arranged as a factorial experiment in a completely randomized design to evaluate the effects of extraction method, extraction temperature and storage time. Each treatment combination was replicated three times. Data were analysed using three-way ANOVA, and the model included the main effects of extraction method (A), temperature (B), and storage time (C), all two-way interactions and the three-way interaction. Specifically, after ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD test was applied for multiple mean comparisons at the significance level of p<0.05.The ZOI values are continuous variables measured in millimeters and are presented as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) from three replicates. Additionally, data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The variables used in this study (e.g., ZOI in millimeters) are continuous quantitative data, and all results are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) based on three replicates.

Results and discussion

Yield and EO composition

Extracted EO is insoluble in water due to its decreased density, pale yellow hue, distinct scent, and high volatility. Various extraction techniques were employed to extract EO from kinnow peel, yielding varying quantities of EO. The extraction yields were as follows: simple HD, 2.10 ml; MAHD, 2.50 ml; UAHD, 2.40 ml; and OHHD, 2.30 ml. The extraction yield was increased by microwave irradiation because it speeds up the breakdown of plant cells and causes intercellular components to diffuse into the liquid solution more quickly (Akbari et al., 2019). In UAHD ultrasonic radiations increased the surface area of the particles by separating them, allowing EO to escape more easily from the peel’s oil glands.

In OHHD electroporation is a non-thermal effect of ohmic heating, inducing permeability in the cell walls and membranes of samples, simplifying EO extraction compared to the HD method. Therefore, it was noticed that there was an increase in the EO yield by MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD novel extraction methods as compared to the conventional HD method. This can be attributed to the increased electric field, which results in increased ion mobility in the peel powder and collisions between molecules, as proposed by Al-Hilphy et al. (2022). The principal elements of the fresh EO extracted by HD, UAHD, OHHD, and MAHD are shown in Table 1.

A B C D

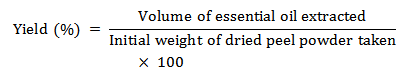

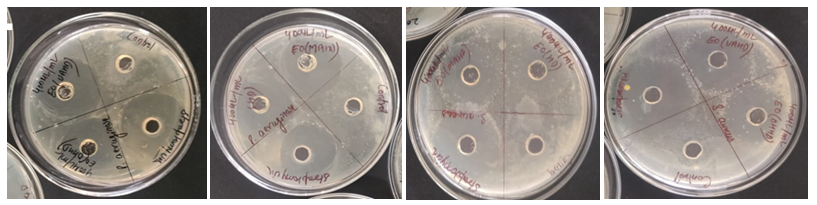

Figure 1: Antibacterial activities of Kinnow peel oil. (A) Pseudomonas aeruginosa with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (B) P. aeruginosa with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (C) Staphylococcus aureus with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (D) S. aureus with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils with methanol and positive control.

A B C D

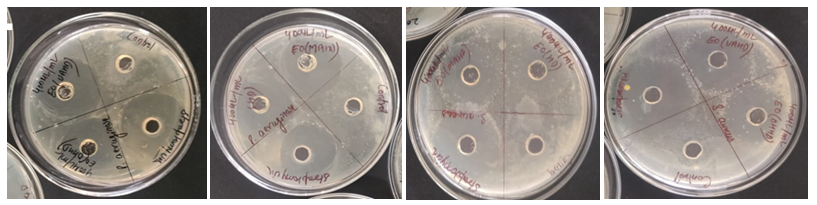

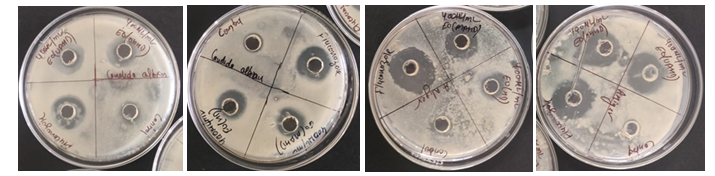

Figure 2: Antifungal activities of Kinnow peel oil. (A) Candida albicans with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (B) C. albicans with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (C) Aspergillus niger with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (D) A. niger with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils with methanol and positive control.

Table 2: Antibacterial activity of citrus reticulate peels oil against bacterial strains

Table 3: Antifungal activity of citrus reticulate peels oil against fungal strains

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 3: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of fresh essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 4: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of 12-month stored at temperature 4 oC essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 5: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of 12-month stored at -10 oC essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmicheating assisted hydrodistillation

Table 4: GC-MS analysis of 12-month stored essential oil extracted from kinnow peel (a) HD, (b) MAHD, (c) UAHD, (d) OHHD temperature 4 oC

Table 5: GC-MS analysis of 12-month stored essential oil extracted from kinnow peel (a) HD, (b) MAHD, (c) UAHD, (d) OHHD temperature -10 oC

K. Yadav 1[*]*

1. Department of Food Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, India

2. Amity Institute of Food Technology, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India

- Kinnow peel oil suppressed the proliferation of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, albeit with varying efficacy.

- The oil exhibited more antibacterial effect against gram-positive bacteria than gram-negative pathogens.

- Limonene and precursors constituted the dominant constituents of the kinnow peel essential oil.

- The composition of the EO experienced slight alterations in response to storage period and temperature.

- Prolonged storage reduced the concentration of low molecular weight compounds within the essential oil.

| Article type Original article |

ABSTRACT Background: The processing of kinnow (Citrus reticulata) juice generates 30–34% peel waste, which is loaded in bioactive compounds like phenolics, limonin, and pectin. This study examined the antibacterial efficacy and storage stability of essential oil (EO) derived from kinnow peel, emphasizing its prospective use in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic sectors. Methods: Kinnow peels were collected from juice venders of Hisar and Sirsa between December 2022 and January 2023. EO was extracted using four methods: Hydrodistillation (HD), Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation (MAHD), Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation (UAHD), and Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation (OHHD). The antimicrobial activity was assessed by the well diffusion technique against established bacterial and fungus strains. For the storage study, oils were kept in amber-colored bottles at refrigerator and freezer temperatures for 12 months. Fresh and stored oils were characterized using FTIR and GC-MS analysis. Data were evaluated utilizing ANOVA in SPSS 25.0, with statistical significance established at p<0.05. Results: The EO exhibited the strongest antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It also exhibits antifungal effects against Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans. FTIR and GC-MS analyses confirmed limonene as the dominant compound. The highest concentrations were found in freshly extracted samples: HD (92.04%), MAHD (85.19%), UAHD (86.09%), and OHHD (85.12%). After 12 months of storage, the limonene content decreased slightly but remained more stable at –10 °C: HD (88.11%), MAHD (84.23%), UAHD (85.24%), and OHHD (84.48%), compared to storage at 4°C: HD (87.06%), MAHD (85.61%), UAHD (84.90%), and OHHD (84.12%). Conclusion: The EO shown greater efficacy against gram-positive bacteria compared to gram-negative pathogens. Prolonged storage reduced low-molecular-weight compounds, though lower temperatures improved retention. These findings suggest that kinnow peel EO holds promise for applications in food preservation and natural antimicrobial formulations. © 2025, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |

|

| Keywords Oils Anti-Bacterial Agents Limonene Food Preservation |

||

| Article history Received: 22 Aug 2024 Revised: 14 Nov 2025 Accepted: 25 Nov 2025 |

||

| Abbreviations EO=Essential Oil FTIR=Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy GC-MS=Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry HD=Hydrodistillation MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation ZOI=Zone of Inhibition |

To cite: Yadav K., Kumar M., Pathera A. (2025). Impact of storage conditions on the antibacterial and antifungal properties of essential oils extracted from kinnow peel. Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control. 12: 271-283.

Introduction

Essential oils (EOs) are a group of volatile, lipophilic secondary metabolites generated by variety of plants, known for their strong and frequently pleasant aroma. They are complex combinations of numerous chemical elements, mainly hydrocarbons, such as monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, which follow the general formula (C5H8)n. These compounds hold a substantial commercial value because of their diverse applications in fragrances, food flavourings, and medicinal products (Widiaswanti et al., 2019). In addition to hydrocarbons, EOs contain oxygenated derivatives, like alcohols, aldehydes, esters, ethers, ketones, phenols, and oxides, contributing to their functional diversity (Espina et al., 2011; Prabuseenivasan et al., 2006).

Depending on the plant's origin, growing environment, and developmental stage, the content of EOs might differ dramatically (Miguel et al., 2004). These variations influence their bioactivity and potential applications. As Farag et al. (1989) noted, EOs are gaining prominence in the food and cosmetic industries because of growing consumer urge for natural alternatives to synthetic additives.

EOs are utilized extensively in the food business for preservation because of their flavor, scent, and natural antibacterial qualities. Consequently, there is an increasing need to investigate other solutions. Peels from citrus fruits are an excellent source of EOs that is high in bioactive substances. Citrus waste valorization improves economic returns and lessens environmental effects when it is included into EO production (Bora et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding how factors like storage conditions affect the stability and chemical constituents of citrus EOs is critical for optimizing practical use in various industries. The present research has primarily focused on extraction procedures and short-term bioactivity testing, with limited attention given to the stability and functionality of EOs during long-term storage and fill this gap by comprehensively assessing the antibacterial properties of kinnow peel EO extracted using various techniques. It also investigated the outcomes of storage duration and conditions on the oil’s chemical stability and antimicrobial efficacy over a 12-month period. The findings were aimed to support the development of natural preservatives and antimicrobial agents derived from citrus waste, contributing to both sustainable waste valorization and natural product research.

The citrus processing sector generates a vast quantity of peels, pulps, and seeds. These account for 45 to 60% of total fruit and are commonly abandoned in nature, having negative impacts on the environment (Hejazi et al., 2022). The breakdown of these wastes can increase soil acidity, affect the water table, and release the EOs that are harmful to fauna and flora (Gavrilescu, 2021). Citrus peels are also very valuable matrices because they are readily available and contain a significant amount of macronutrients and micronutrients (water, proteins, sugars, minerals, EOs, fibers, carotenoids, vitamin C, and phenolic compounds) with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antioxidant qualities (Gavrilescu, 2021; Majdanand and Bobrowska-Korczak, 2022). The Most common method to valorize natural compounds is to isolate EO or extract and test them as antibacterial and antifungal agents (Abdou et al., 2022; Achir et al., 2022; Maaghloud et al., 2024; Napoli and Di Vito, 2021).

One important physiologically active ingredient in citrus peel is EO. Citrus peel oil glands are rich in it (Boussaada et al., 2007). It typically makes about 1-3% of the orange peel's fresh weight (Njoroge et al., 2005). Depending on the citrus type and growth conditions, there are tens to hundreds of distinct compounds that make up citrus EO (Sharma et al., 2017). This EO is extensively utilized in chemical, culinary, and medical areas because of its appealing aroma, antioxidant qualities, and antibacterial activity. Its natural product features are particularly appealing. There is limited chemical information available on how EOs' compositions change during storage.

The significance of the present research is that it described the chemical compositions of Eos extracted from the kinnow peel, as well as their potential for inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms, and analyzed the effect of storage parameters on the chemical makeup of kinnow peel EO. Citrus reticulate EO components were analyzed under refrigerator (4 °C) and freezer (−10 °C) storage conditions for twelve months.

Materials and methods

Materials

The kinnow peel utilized in present study was gathered from the Sirsa and Hisar markets' juice vendors. Every scrape was dried at 30–40 °C in a hot air oven (MSW-211, MAC, India). The resulting dried peel was then processed into a powder using a professional grinder (Sujata, India). The powder was kept at 4±0.2 °C after being packed into Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) pouches.

Extraction methods

-Hydrodistillation (HD)

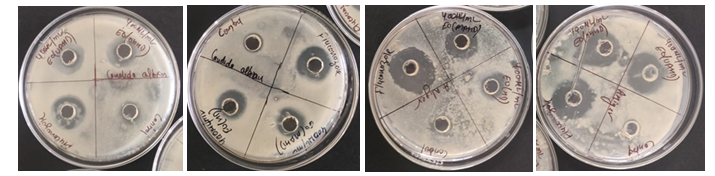

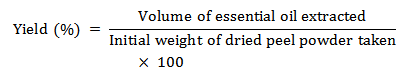

Conventional HD was performed using a Clevenger apparatus at 80 °C for five h. In a 1000 ml flask, 100 g of dried kinnow peel powder was dissolved in 700 ml of distilled water (Shaw et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2021). EO was stored at 4±0.2 °C. The yield was expressed as follows:

Depending on the plant's origin, growing environment, and developmental stage, the content of EOs might differ dramatically (Miguel et al., 2004). These variations influence their bioactivity and potential applications. As Farag et al. (1989) noted, EOs are gaining prominence in the food and cosmetic industries because of growing consumer urge for natural alternatives to synthetic additives.

EOs are utilized extensively in the food business for preservation because of their flavor, scent, and natural antibacterial qualities. Consequently, there is an increasing need to investigate other solutions. Peels from citrus fruits are an excellent source of EOs that is high in bioactive substances. Citrus waste valorization improves economic returns and lessens environmental effects when it is included into EO production (Bora et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding how factors like storage conditions affect the stability and chemical constituents of citrus EOs is critical for optimizing practical use in various industries. The present research has primarily focused on extraction procedures and short-term bioactivity testing, with limited attention given to the stability and functionality of EOs during long-term storage and fill this gap by comprehensively assessing the antibacterial properties of kinnow peel EO extracted using various techniques. It also investigated the outcomes of storage duration and conditions on the oil’s chemical stability and antimicrobial efficacy over a 12-month period. The findings were aimed to support the development of natural preservatives and antimicrobial agents derived from citrus waste, contributing to both sustainable waste valorization and natural product research.

The citrus processing sector generates a vast quantity of peels, pulps, and seeds. These account for 45 to 60% of total fruit and are commonly abandoned in nature, having negative impacts on the environment (Hejazi et al., 2022). The breakdown of these wastes can increase soil acidity, affect the water table, and release the EOs that are harmful to fauna and flora (Gavrilescu, 2021). Citrus peels are also very valuable matrices because they are readily available and contain a significant amount of macronutrients and micronutrients (water, proteins, sugars, minerals, EOs, fibers, carotenoids, vitamin C, and phenolic compounds) with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antioxidant qualities (Gavrilescu, 2021; Majdanand and Bobrowska-Korczak, 2022). The Most common method to valorize natural compounds is to isolate EO or extract and test them as antibacterial and antifungal agents (Abdou et al., 2022; Achir et al., 2022; Maaghloud et al., 2024; Napoli and Di Vito, 2021).

One important physiologically active ingredient in citrus peel is EO. Citrus peel oil glands are rich in it (Boussaada et al., 2007). It typically makes about 1-3% of the orange peel's fresh weight (Njoroge et al., 2005). Depending on the citrus type and growth conditions, there are tens to hundreds of distinct compounds that make up citrus EO (Sharma et al., 2017). This EO is extensively utilized in chemical, culinary, and medical areas because of its appealing aroma, antioxidant qualities, and antibacterial activity. Its natural product features are particularly appealing. There is limited chemical information available on how EOs' compositions change during storage.

The significance of the present research is that it described the chemical compositions of Eos extracted from the kinnow peel, as well as their potential for inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms, and analyzed the effect of storage parameters on the chemical makeup of kinnow peel EO. Citrus reticulate EO components were analyzed under refrigerator (4 °C) and freezer (−10 °C) storage conditions for twelve months.

Materials and methods

Materials

The kinnow peel utilized in present study was gathered from the Sirsa and Hisar markets' juice vendors. Every scrape was dried at 30–40 °C in a hot air oven (MSW-211, MAC, India). The resulting dried peel was then processed into a powder using a professional grinder (Sujata, India). The powder was kept at 4±0.2 °C after being packed into Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) pouches.

Extraction methods

-Hydrodistillation (HD)

Conventional HD was performed using a Clevenger apparatus at 80 °C for five h. In a 1000 ml flask, 100 g of dried kinnow peel powder was dissolved in 700 ml of distilled water (Shaw et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2021). EO was stored at 4±0.2 °C. The yield was expressed as follows:

-Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation (MAHD)

MAHD was conducted using a household microwave oven (IFB 20PG4S, IFB, India). The power source had a maximum output power of 800 W and a frequency of 2450 MHz. In a 1000 ml beaker, 700 ml of distilled water were used to dissolve 100 g of powdered dried kinnow peel. The flask was placed in the 400 W microwave (IFB 20PG4S, IFB, India) oven for 20 min. The solution was moved into the conical flask and HD was carried out after the microwave treatment (Yu et al., 2021).

-Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation (UAHD)

UAHD was carried out using an Ultrasonic Probe Sonicator (Biogene, India, BGS-185B, 750 W). A mixture of 100 g dried kinnow peel powder and 700 ml distilled water was prepared in a 1000 ml beaker. The ultrasonic probe was applied with a two-second pulse at 225 W for 20 min. After ultrasonication, the treated solution was transferred to a conical flask for HD (Yu et al., 2021).

-Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation (OHHD)

OHHD was carried out utilizing a specifically built device with platinum electrodes developed at the Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology's Food Technology Department. In the ohmic heating assembly, 100 g of dried peel powder were dissolved in 700 ml of distilled water while maintaining the ohmic heating temperature (70 °C), voltage (220 V), and salt (NaCl) concentration (2%). Following the ohmic heating treatment, the procedure's steps were quite similar to those of the HD process. Throughout the procedure, temperature, voltage, and salt content were carefully monitored (Al-Hilphy et al., 2022; Kristinawati et al., 2020).

EO storage conditions

To investigate the impact of different storage conditions on the chemical compositions of distilled oils, oil samples were kept in freezers (−10 °C) and refrigerators (4 °C) for 12 months in dark amber-colored bottles before the analysis. The oil analysis was analyzed over a one-year period for all storage treatments. Freshly extracted oil was also analyzed immediately to establish a baseline, thereby isolating the specific effects of storage conditions on the EO composition. The extracted Eos were light yellowish with a pungent odour.

Compound identification

-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopyanalysis (FTIR)

The EOs of kinnow fruit peel was analyzed using a Fourier transmission infrared spectrophotometer (Spectrum Two, PerkinElmer, USA). The KBr powder (Fisher Scientific, USA) was homogeneously pulverized in a crystal pestle and mortar. The fine powder was subsequently compressed into a homogeneous, thin particle using a hydraulic pellet press (Eagle Press and Equipment Co., Ltd., Canada). The EOs sample was directly placed on the surface of a pair of rectangular sodium chloride plates at room temperature, and measurements were taken in the IR region at 4000-400 cm-1. Two surveys were conducted at a speed of 3 cm/s for each EO, with an air spectrum serving as a reference. The FTIR study was carried out at GJUS&T Hisar Central Instrumentation Laboratory (Sandhu et al., 2021).

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis (GC-MS)

The extracted EOs were evaluated using a GC-MS equipment from Thermo Fisher Scientific in the USA. The instrument featured a GC-Trace 1300, MS-TQS Duo, and Autosampler-TriPlus RSH, connected with a DB-5MS column (length of 40 m, inner diameter of 0.15µm, and film thickness of 0.15µm). For sample preparation, 20 ul of material was dissolved in methanol and the volume was increased to 1 ml using the same solvent, as reported by Van et al. (2022) with minor modifications. Then, 1 ml of EO was injected into the GC-Trace 1300, MS-TQS Duo, and Autosampler-TriPlus RSH, all connected to a DB-5MS column. The fore line pressure temperature was set to 210 oC, the transfer line temperature was 200 oC, and the ionization mode was Electron Impact (EI) at 70 eV. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with an injection volume of 1 µl and an injector temperature of 200 oC. Temperatures varied from 50 oC (held for 5 min) to 210 oC (held for 15 min) during the GC analysis, using a 5 oC/min ramp rate. The mass range for analyte characterization was adjusted to 45–450 (m/z).

The obtained results were compiled by comparing the spectra with the inbuilt National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library, facilitating the identification of components present in the EOs.

Antibacterial activity assay

Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus as well as Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa were used as test organisms to determine antibacterial activity. The bacterial strains were obtained from the Departments of Bio Nano Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. Antibacterial activity was measured as the Zone of Inhibition (ZOI) using the well diffusion method (Anwar et al., 2023).First, 100 ul of the culture suspension was shifted to a petri dish containing Nutrient Agar medium. Then, a 7 mm diameter borer was used to form a well in the agar plate and fill it with EO solution in methanol (400µl/ml). Streptomycin (standard solution) 50 mg was dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water and placed into wells (20µl/well) and methanol (control). The dishes were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The antibacterial activity was determined through determining the diameter of the bacterial ZOI in millimeters.

Antifungal activity

Two fungal strains Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans were tested to determine the antifungal activities of kinnow peel EO which was extracted by different methods. The bacterial strains were obtained from the Departments of Bio Nano Technology, Guru Jambheshwar University of Science and Technology, Hisar, Haryana, India. Active cultures were created by transferring a loopful of cells from stock cultures to flasks containing potato dextrose broth and incubated at 24 oC for 48 h.

First, 100 ul of the fungal suspension was spread on pert dish containing Potato Dextrose Agar medium. A well was then created in the agar plate with a7mm borer and filled the well with EO solution in methanol (400 ul/ml) with 20ul in each well. Fluconazole was diluted in 100 ml distilled water and placed into wells (20 ul/well) and methanol solution, which served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Plates were then incubated at 25 oC for four days. The antibacterial activity was determined by measuring the fungal ZOI diameter in millimeters (Van et al., 2022).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was arranged as a factorial experiment in a completely randomized design to evaluate the effects of extraction method, extraction temperature and storage time. Each treatment combination was replicated three times. Data were analysed using three-way ANOVA, and the model included the main effects of extraction method (A), temperature (B), and storage time (C), all two-way interactions and the three-way interaction. Specifically, after ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD test was applied for multiple mean comparisons at the significance level of p<0.05.The ZOI values are continuous variables measured in millimeters and are presented as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) from three replicates. Additionally, data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The variables used in this study (e.g., ZOI in millimeters) are continuous quantitative data, and all results are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) based on three replicates.

Results and discussion

Yield and EO composition

Extracted EO is insoluble in water due to its decreased density, pale yellow hue, distinct scent, and high volatility. Various extraction techniques were employed to extract EO from kinnow peel, yielding varying quantities of EO. The extraction yields were as follows: simple HD, 2.10 ml; MAHD, 2.50 ml; UAHD, 2.40 ml; and OHHD, 2.30 ml. The extraction yield was increased by microwave irradiation because it speeds up the breakdown of plant cells and causes intercellular components to diffuse into the liquid solution more quickly (Akbari et al., 2019). In UAHD ultrasonic radiations increased the surface area of the particles by separating them, allowing EO to escape more easily from the peel’s oil glands.

In OHHD electroporation is a non-thermal effect of ohmic heating, inducing permeability in the cell walls and membranes of samples, simplifying EO extraction compared to the HD method. Therefore, it was noticed that there was an increase in the EO yield by MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD novel extraction methods as compared to the conventional HD method. This can be attributed to the increased electric field, which results in increased ion mobility in the peel powder and collisions between molecules, as proposed by Al-Hilphy et al. (2022). The principal elements of the fresh EO extracted by HD, UAHD, OHHD, and MAHD are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: GC-MS analysis of fresh essential oil extracted from kinnow peel (a) HD, (b) MAHD, (c) UAHD, (d) OHHD

| RT | Compound name | Fresh essential oil (Peak area) | |||

| HD | UAHD | MAHD | OHHD | ||

| 6.28 | à-Pinene | 1.33 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.20 |

| 6.39 | (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1. 1]hept-2-ene | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.48 |

| 7.13 | á-Myrcene | 1.43 | 1.83 | 1.78 | 1.53 |

| 7.36 | Octanal | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.23 |

| 7.42 | D-limonene | 92.04 | 86.09 | 85.19 | 85.12 |

| 9.11 | Linalool | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| 10.78 | 3-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, Terpinen-4-ol | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.44 |

| 11.02 | à-Terpineol | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.81 |

| 11.56 | 2-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl), Carveol | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.80 |

| 20.08 | 2,6,11-Dodecatrienal, 2,6-dimethyl-10-methylene | 0.55 | 0.90 | 0.58 | 0.92 |

| 22.20 | Carvacrol, TBDMS derivative | ND | 6.17 | 5.62 | 5.59 |

GC-MS=Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; ND=Not Detected; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; RT=Retention Time; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation

Antibacterial and antifungal assay

Citrus reticulate EO's antibacterial activity towards S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was measured using the ZOI method, as shown in Table 2. The well diffusion method revealed that EO has strong antibacterial action on several tested bacterial strains. Figure 1 show that the greatest antibacterial activity of kinnow peel EO was detected against S. aureus with a ZOI ranging from 17.03mm to 16.94 mm, whereas the ZOI for P. aeruginosa was 12.67 mm to 10.13 mm. The maximum ZOI for EO extracted using UAHD may be attributed to its antimicrobial properties, primarily due to its major chemical component. However, the antagonistic or synergistic effects of other ingredients in the combination must also be addressed.

Therefore, S. aureus has the highest ZOI and the slowest growth, whereas P. aeruginosa has the lowest ZOI and the fastest growth. The current investigation found that the extracted EO was more efficient against gram-positive than gram-negative bacteria.

Citrus reticulate EO's antibacterial activity towards S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was measured using the ZOI method, as shown in Table 2. The well diffusion method revealed that EO has strong antibacterial action on several tested bacterial strains. Figure 1 show that the greatest antibacterial activity of kinnow peel EO was detected against S. aureus with a ZOI ranging from 17.03mm to 16.94 mm, whereas the ZOI for P. aeruginosa was 12.67 mm to 10.13 mm. The maximum ZOI for EO extracted using UAHD may be attributed to its antimicrobial properties, primarily due to its major chemical component. However, the antagonistic or synergistic effects of other ingredients in the combination must also be addressed.

Therefore, S. aureus has the highest ZOI and the slowest growth, whereas P. aeruginosa has the lowest ZOI and the fastest growth. The current investigation found that the extracted EO was more efficient against gram-positive than gram-negative bacteria.

A B C D

Figure 1: Antibacterial activities of Kinnow peel oil. (A) Pseudomonas aeruginosa with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (B) P. aeruginosa with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (C) Staphylococcus aureus with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (D) S. aureus with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils with methanol and positive control.

The antifungal efficacy of extracted EO against A. niger and C. albicans was evaluated by comparing ZOI measurements. The data obtained (Table 3) showed that EO has substantial antifungal action. Kinnow peel EO had the strongest antifungal activity against A. niger, with ZOI ranging from 7.68 mm to 10.12 mm (Figure 2). The ZOI for C. albicans ranged from 8.76 mm to 9.32 mm.

A B C D

Figure 2: Antifungal activities of Kinnow peel oil. (A) Candida albicans with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (B) C. albicans with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (C) Aspergillus niger with hydrodistillation and microwave assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils, (D) A. niger with ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation and ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation extracted oils with methanol and positive control.

Table 2: Antibacterial activity of citrus reticulate peels oil against bacterial strains

| Essential oil | Staphylococcus aureus (ZOI, mm) | Positive control | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ZOI, mm) |

Positive control |

| EO extracted by HD | 17.03±0.07 | 22.3±0.10 | 10.13±0.15 | 15.06±0.07 |

| EO extracted by UAHD | 17.62±1.01 | 24.5±0.08 | 12.67±0.23 | 17.4±0.11 |

| EO extracted by MAHD | 17.11±0.19 | 22.3±0.10 | 11.86±0.16 | 15.06±0.07 |

| EO extracted by OHHD | 16.94±0.11 | 24.5±0.08 | 11.12±1.17 | 17.4±0.11 |

Values are means ± Standard Deviation (SD). Significant differences among treatments is p<0.05.

EO=Essential Oil; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation; ZOI=Zone Of Inhibition

EO=Essential Oil; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation; ZOI=Zone Of Inhibition

The current investigation found that the extracted EO was more efficient against gram-positive bacteria than gram-negative bacteria, which is consistent with prior findings. This difference is likely because of the more complicated wall structure of gram-negative bacteria, due to the lipopolysaccharide layer, and there may be relative impermeability of Gram-negative bacteria's outer membranes when compared to gram-positive bacteria (Geraci et al., 2017). Result of the current study agreed with previous studies, like as Ben Hsouna et al. (2017) who reported that citrus lemon EO are more active against gram-positive than gram-negative; however, it was contrary to many others researchers, such as Anwar et al., (2023), who invesgated that citrus sinensis peel oil was more effective in case of gram negative bacteria.

The variation in observation might be attributed to harvesting the sample at a different ripening stage, which considerably alters the antibacterial properties (Bhandari et al., 2021; Değirmenci et al., 2020). Several authors have attributed the antibacterial activities of citrus EOs to the presence of components such as D-limonene, linalool, or citral, which are found in variable concentrations (Bezić et al., 2005, Tepe et al., 2006).

The variation in observation might be attributed to harvesting the sample at a different ripening stage, which considerably alters the antibacterial properties (Bhandari et al., 2021; Değirmenci et al., 2020). Several authors have attributed the antibacterial activities of citrus EOs to the presence of components such as D-limonene, linalool, or citral, which are found in variable concentrations (Bezić et al., 2005, Tepe et al., 2006).

Table 3: Antifungal activity of citrus reticulate peels oil against fungal strains

| Essential oil | Aspergillus niger (ZOI, mm) |

Positive control | Candida albicans (ZOI, mm) |

Positive control |

| EO extracted by HD | 7.68±0.06 | 15.65±0.12 | 8.76±0.04 | 13.11±0.09 |

| EO extracted by UAHD | 10.12±0.20 | 15.28±0.15 | 9.32±0.13 | 13.02±0.10 |

| EO extracted by MAHD | 10.11±1.10 | 15.65±0.12 | 9.18±0.08 | 13.11±0.11 |

| EO extracted by OHHD | 9.93±0.61 | 15.28±0.15 | 9.23±1.01 | 13.02±0.10 |

Values are means ± Standard Deviation (SD). Significant differences among treatments is p<0.05.

EO=Essential Oil; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation; ZOI=Zone Of Inhibition

EO=Essential Oil; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation; ZOI=Zone Of Inhibition

Another reason for slightly less active antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria may be the less susceptibility to the action of antibacterial. This is most likely owing to their outer membrane, which covers the cell wall and limits the transport of hydrophobic substances via its lipopolysaccharide coating (Ben Hsouna et al., 2017).

Previous research has shown that citrus oil has biological activities like antioxidants, anti-cancer, and antibacterial activities (Kamel et al., 2022). This could be because these compounds can damage bacterial cell membranes, rendering them permeable and eventually resulting to death through ion and molecule leakage (Anwar et al., 2023). A study found that C. reticulate EO has a wide range of effects on microorganisms. The oil was shown to be the most potent at regulate microbial growth and sporulation (Abbasi et al., 2021). The antibacterial properties of EOs are most likely owing to the existence of a single component, synergism, or antagonism among different components (Anwar et al., 2023).

The outcomes revealed that gram-positive bacteria were the most effective at inhibiting or killing visible bacterial growth; these results were accordant with previous research (Sreepian et al., 2019). Previous study on citrus EO discovered greater ZOI against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria than in the current investigation. This could be attributed to harvest of samples in varying ripening stages affecting the antibacterial activity (Bourgou et al., 2012; Degirmenci and Erkurt, 2020). Furthermore, Han et al. (2019) reported that limonene greatly inhibited antibacterial action, ruptured the cell covering of bacteria, and caused alter in morphology.

According to Long et al. (2023), EOs operates on microbial cells through a variety of mechanisms. For example, EOs has the ability to penetrate cells, enhance the permeability of the cell membrane, and denature proteins. Moreover, they can harm the cell covering and prevent the creation of peptidoglycans through the cell wall, as well as prevent Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) synthesis through energy metabolism. Terpenoids and phenolic chemicals in EOs have been demonstrated in earlier studies to impede bacterial DNA replication and restore (Ni et al., 2021). EO's antibacterial activities are thought to be linked to phytochemical elements such as monoterpenes, which permeate into and harm cell membrane composition (Matasyoh et al., 2007). Citral serves as a fungicidal agent by forming a charge transfer complex with an electron donor in fungal cells, resulting in fungal death, as demonstrated by Kurita et al. (1981). The present study uniquely characterizes the antibacterial activity of Kinnow peel EO by comparing extracts obtained from several different techniques.

Storage study of extracted EO

The chemical makeup of EOs can be influenced by various storage conditions. There has been little investigation into the preservation of plant secondary metabolites, notably, EOs because these molecules are volatile and can undergo a variety of modifications depending on the storage conditions. In this study, the components of HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD distilled EOs of kinnow peel were examined at various storage temperatures (4 °C and -10 °C) and times.

-FTIR spectroscopic analysis of kinnow peel EO samples

The FTIR spectra of the specified EO samples revealed relatively intense bands associated with specific vibrations of the necessary functional groups found in components usually employed for this type of sample. EOs is concentrated solutions of volatile molecules formed of complex homogeneous mixtures of diverse chemicals, with over 100 ingredients in each species (taxon) (Agatonovic-Kustrin et al., 2020). Their FTIR spectra get intricate when the spectra of different elements overlap and different vibrational modes merge.

The FTIR spectra of fresh EO, stored at 4 °C were compared with those of EO stored at -10 °C in dark amber-colored bottles in the 4000-400 cm-1 range. The infrared spectra showed a broad spectrum at 3435 cm-1, showing an O-H stretch of alcohol, as well as vibrations in the 3000-2856 cm-1range, indicating a substantial asymmetric stretching of -CH3, which conformed to the compound's alkyl-saturated aliphatic group. However, the peak at 3084 cm-1 defined the existence of an aromatic stretch. Bending vibrations were observed for the-CH3 group at 1375 cm-1, while the -CH2 group was at 1452 cm-1. The stretching of -C-O appeared between 1267 and 1016 cm-1, and a peak at around 1634 cm-1 indicatedthe existence of an aromatic functional group. Saturated hydrocarbon C-H stretching absorption was also detected at 2966 cm-1.

Limonene accounts for over 90% of the EO obtained from orange peel, while lemon contributes slightly less than 70% (Wei and Shibamoto, 2010). Notably, the absorption at 887 cm-1 indicated the existence of limonene. The FTIR analysis of numerous EOs indicated similar absorption bands with very modest variations in strength. The outcomes were established by the FTIR, which recognized vibrational patterns of limonene at 887 cm-1 (out-of-plane bending of terminal methylene group), 1436-1436 cm-1 (C-H asymmetric and symmetric bend), and 1644 cm-1 (C=O stretching vibration), which were also observed by GC-MS analysis.

Given the presence of two double bonds in limonene's molecular structure, it is anticipated that there will be two bands for C=C stretching. The strong and broadband at around 1433 cm-1 was caused by the CH3 / CH2 bending mode. The powerful signals at 763 and 757 cm-1 were a result of a ring deformation mode of limonene (Schulz and Baranska, 2007). The presence of a prominent methylene/methyl band at 1435-1436 cm-1, a less intense methyl band at 13175-1376 cm-1, and a methylene rocking vibration band at 758-759 cm-1 indicatedthe existence of a linear aliphatic structure with a long carbon chain (Madivoli et al., 2012). Pollard et al. (2016) discovered that the FTIR spectra of undiluted Rosemary EO displayed the anticipated stretching of C-H bonds at approximately 2900 cm-1, C=O bonds at around 1700

cm-1, a broad stretching of O-H bonds at around 3400

cm-1, and stretching (~1100 cm-1) of terpenoid constituents.

The constituents and compositions of EOs can vary greatly depending on the geochemistry of the soil where the plant grows. EOs commonly contains terpenes like terpineol, cineole, and citronellal. Oliveira et al. (2016) found that concentrated EOs have predicted terpenoid components in their Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) absorption spectrum, such as C-H stretch (~2900 cm-1), C=O stretch (~1700 cm−1), broad O-H stretch (~3400 cm-1), and C-O stretch (~1100 cm-1). These oils' FTIR spectra mostly displayed monoterpene vibrational modes at 886, 1436, and 1644 cm-1. While lemon myrtle, oregano (terpineol type), and peppermint oil had lower wave numbers, the C=O stretching band at 1740 cm-1 in lavender, rosemary, and sage oil was effective for differential identification (Oliveira et al., 2016; Rummens, 1963).

-GC-MS analysis of kinnow peel EO Samples (fresh and stored)

The GC-MS analysis revealed the existence of a diverse varities of chemicals in EOs extracted using various procedures. The GC-MS outcomes showed that the EOs contained a broad range of chemical compounds lies on the extraction method applied. Chromatograms of the freshly extracted oils (Figure 3), as well as those stored at 4 °C (Figure 4) and –10°C (Figure 5) for 12 months, displayed numerous peaks. These peaks pointed to the presence of many different phytochemicals. Clear differences in the number and height of the peaks appeared between the methods and storage temperatures, highlighting how both processing and preservation impact the oils' chemical makeup. These chemicals are used to compare extracted EOs qualitatively, while yield value is utilized to evaluate them quantitatively. Similar active compounds were found in HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD extracted EO. D-limonene was the most common constituent in Kinnow Peel EO.

Ferhat et al. (2006) reported that limonene was the most frequent component in the EO obtained from orange peel. The GC-MS data showed the EOs recovered by HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD had remarkably alike compositions. The compounds of EOs extracted from kinnow peel via these methods, were studied at various temperatures (fresh extracted, 4 °C, and -10 °C) and storage times (12 months). The current study found that monoterpene known as limonene and their precursors were the predominant components in kinnow peel EO samples immediately following distillation via HD (92.04%), MAHD (85.19%), UAHD (86.09%), and OHHD (85.12%), and/or under various storage settings over the experiment period. Following the storage of EO in dark amber colored bottles at temperature 4 oC and -10 oC for 12 months, limonene content levels were: HD (87.06%), MAHD (85.61%), UAHD (84.90%), and OHHD (84.12%) at 4 oC and HD (88.11%), MAHD (84.23%), UAHD (85.24%), and OHHD (84.48 %)

at -10 oC.

Previous research has shown that citrus oil has biological activities like antioxidants, anti-cancer, and antibacterial activities (Kamel et al., 2022). This could be because these compounds can damage bacterial cell membranes, rendering them permeable and eventually resulting to death through ion and molecule leakage (Anwar et al., 2023). A study found that C. reticulate EO has a wide range of effects on microorganisms. The oil was shown to be the most potent at regulate microbial growth and sporulation (Abbasi et al., 2021). The antibacterial properties of EOs are most likely owing to the existence of a single component, synergism, or antagonism among different components (Anwar et al., 2023).

The outcomes revealed that gram-positive bacteria were the most effective at inhibiting or killing visible bacterial growth; these results were accordant with previous research (Sreepian et al., 2019). Previous study on citrus EO discovered greater ZOI against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria than in the current investigation. This could be attributed to harvest of samples in varying ripening stages affecting the antibacterial activity (Bourgou et al., 2012; Degirmenci and Erkurt, 2020). Furthermore, Han et al. (2019) reported that limonene greatly inhibited antibacterial action, ruptured the cell covering of bacteria, and caused alter in morphology.

According to Long et al. (2023), EOs operates on microbial cells through a variety of mechanisms. For example, EOs has the ability to penetrate cells, enhance the permeability of the cell membrane, and denature proteins. Moreover, they can harm the cell covering and prevent the creation of peptidoglycans through the cell wall, as well as prevent Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) synthesis through energy metabolism. Terpenoids and phenolic chemicals in EOs have been demonstrated in earlier studies to impede bacterial DNA replication and restore (Ni et al., 2021). EO's antibacterial activities are thought to be linked to phytochemical elements such as monoterpenes, which permeate into and harm cell membrane composition (Matasyoh et al., 2007). Citral serves as a fungicidal agent by forming a charge transfer complex with an electron donor in fungal cells, resulting in fungal death, as demonstrated by Kurita et al. (1981). The present study uniquely characterizes the antibacterial activity of Kinnow peel EO by comparing extracts obtained from several different techniques.

Storage study of extracted EO

The chemical makeup of EOs can be influenced by various storage conditions. There has been little investigation into the preservation of plant secondary metabolites, notably, EOs because these molecules are volatile and can undergo a variety of modifications depending on the storage conditions. In this study, the components of HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD distilled EOs of kinnow peel were examined at various storage temperatures (4 °C and -10 °C) and times.

-FTIR spectroscopic analysis of kinnow peel EO samples

The FTIR spectra of the specified EO samples revealed relatively intense bands associated with specific vibrations of the necessary functional groups found in components usually employed for this type of sample. EOs is concentrated solutions of volatile molecules formed of complex homogeneous mixtures of diverse chemicals, with over 100 ingredients in each species (taxon) (Agatonovic-Kustrin et al., 2020). Their FTIR spectra get intricate when the spectra of different elements overlap and different vibrational modes merge.

The FTIR spectra of fresh EO, stored at 4 °C were compared with those of EO stored at -10 °C in dark amber-colored bottles in the 4000-400 cm-1 range. The infrared spectra showed a broad spectrum at 3435 cm-1, showing an O-H stretch of alcohol, as well as vibrations in the 3000-2856 cm-1range, indicating a substantial asymmetric stretching of -CH3, which conformed to the compound's alkyl-saturated aliphatic group. However, the peak at 3084 cm-1 defined the existence of an aromatic stretch. Bending vibrations were observed for the-CH3 group at 1375 cm-1, while the -CH2 group was at 1452 cm-1. The stretching of -C-O appeared between 1267 and 1016 cm-1, and a peak at around 1634 cm-1 indicatedthe existence of an aromatic functional group. Saturated hydrocarbon C-H stretching absorption was also detected at 2966 cm-1.

Limonene accounts for over 90% of the EO obtained from orange peel, while lemon contributes slightly less than 70% (Wei and Shibamoto, 2010). Notably, the absorption at 887 cm-1 indicated the existence of limonene. The FTIR analysis of numerous EOs indicated similar absorption bands with very modest variations in strength. The outcomes were established by the FTIR, which recognized vibrational patterns of limonene at 887 cm-1 (out-of-plane bending of terminal methylene group), 1436-1436 cm-1 (C-H asymmetric and symmetric bend), and 1644 cm-1 (C=O stretching vibration), which were also observed by GC-MS analysis.

Given the presence of two double bonds in limonene's molecular structure, it is anticipated that there will be two bands for C=C stretching. The strong and broadband at around 1433 cm-1 was caused by the CH3 / CH2 bending mode. The powerful signals at 763 and 757 cm-1 were a result of a ring deformation mode of limonene (Schulz and Baranska, 2007). The presence of a prominent methylene/methyl band at 1435-1436 cm-1, a less intense methyl band at 13175-1376 cm-1, and a methylene rocking vibration band at 758-759 cm-1 indicatedthe existence of a linear aliphatic structure with a long carbon chain (Madivoli et al., 2012). Pollard et al. (2016) discovered that the FTIR spectra of undiluted Rosemary EO displayed the anticipated stretching of C-H bonds at approximately 2900 cm-1, C=O bonds at around 1700

cm-1, a broad stretching of O-H bonds at around 3400

cm-1, and stretching (~1100 cm-1) of terpenoid constituents.

The constituents and compositions of EOs can vary greatly depending on the geochemistry of the soil where the plant grows. EOs commonly contains terpenes like terpineol, cineole, and citronellal. Oliveira et al. (2016) found that concentrated EOs have predicted terpenoid components in their Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) absorption spectrum, such as C-H stretch (~2900 cm-1), C=O stretch (~1700 cm−1), broad O-H stretch (~3400 cm-1), and C-O stretch (~1100 cm-1). These oils' FTIR spectra mostly displayed monoterpene vibrational modes at 886, 1436, and 1644 cm-1. While lemon myrtle, oregano (terpineol type), and peppermint oil had lower wave numbers, the C=O stretching band at 1740 cm-1 in lavender, rosemary, and sage oil was effective for differential identification (Oliveira et al., 2016; Rummens, 1963).

-GC-MS analysis of kinnow peel EO Samples (fresh and stored)

The GC-MS analysis revealed the existence of a diverse varities of chemicals in EOs extracted using various procedures. The GC-MS outcomes showed that the EOs contained a broad range of chemical compounds lies on the extraction method applied. Chromatograms of the freshly extracted oils (Figure 3), as well as those stored at 4 °C (Figure 4) and –10°C (Figure 5) for 12 months, displayed numerous peaks. These peaks pointed to the presence of many different phytochemicals. Clear differences in the number and height of the peaks appeared between the methods and storage temperatures, highlighting how both processing and preservation impact the oils' chemical makeup. These chemicals are used to compare extracted EOs qualitatively, while yield value is utilized to evaluate them quantitatively. Similar active compounds were found in HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD extracted EO. D-limonene was the most common constituent in Kinnow Peel EO.

Ferhat et al. (2006) reported that limonene was the most frequent component in the EO obtained from orange peel. The GC-MS data showed the EOs recovered by HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD had remarkably alike compositions. The compounds of EOs extracted from kinnow peel via these methods, were studied at various temperatures (fresh extracted, 4 °C, and -10 °C) and storage times (12 months). The current study found that monoterpene known as limonene and their precursors were the predominant components in kinnow peel EO samples immediately following distillation via HD (92.04%), MAHD (85.19%), UAHD (86.09%), and OHHD (85.12%), and/or under various storage settings over the experiment period. Following the storage of EO in dark amber colored bottles at temperature 4 oC and -10 oC for 12 months, limonene content levels were: HD (87.06%), MAHD (85.61%), UAHD (84.90%), and OHHD (84.12%) at 4 oC and HD (88.11%), MAHD (84.23%), UAHD (85.24%), and OHHD (84.48 %)

at -10 oC.

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 3: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of fresh essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 4: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of 12-month stored at temperature 4 oC essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmic heating assisted hydrodistillation

.PNG)

.PNG)

(A) (B)

.PNG)

.PNG)

(C) (D)

Figure 5: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry analysis of 12-month stored at -10 oC essential oil extracted from kinnow peel; (A) Hydrodistillation, (B) Microwave assisted hydrodistillation, (C) Ultrasonic assisted hydrodistillation, (D) Ohmicheating assisted hydrodistillation

The analysis of EO contents at different storage temperatures and times indicated the concentrations of key chemicals varied only slightly during refrigerator and freezer storage (Figures 3, 4, and 5), as stated in Table 4 and 5.

All extraction processes yielded EOs with myrceneand α-pinene. Its organoleptic qualities remained almost intact after a year of being kept in a dark glass bottle. Current research findings indicated that increased storage period decreased the concentration of compounds with lower molecular weight (II). This effect could be induced by evaporation, oxidation, or other undesirable swap in EO components over the storage period (Baritaux et al., 1992; Mockute et al., 2005). The concentration of the more volatile chemicals decreased noticeably in the refrigerator over time, while the freezing point was only marginally lowered. The same results were seen at freezer and refrigerator temperatures, with myrcene and pinene showing a declining trend over time. Monoterpenoids were the most often found constituent in kinnow peel EO. Mehdizadeh et al. (2017) investigated how cumin EO quality was influenced by storage temperature. Cumin aldehyde (45.45-64.31%) increased during cumin oil storage, but lower boiling temperature components like β-pinene (1.57-10.03%) and p-cymene (14.93-24.9%) decreased at ambient temperatures.

All extraction processes yielded EOs with myrceneand α-pinene. Its organoleptic qualities remained almost intact after a year of being kept in a dark glass bottle. Current research findings indicated that increased storage period decreased the concentration of compounds with lower molecular weight (II). This effect could be induced by evaporation, oxidation, or other undesirable swap in EO components over the storage period (Baritaux et al., 1992; Mockute et al., 2005). The concentration of the more volatile chemicals decreased noticeably in the refrigerator over time, while the freezing point was only marginally lowered. The same results were seen at freezer and refrigerator temperatures, with myrcene and pinene showing a declining trend over time. Monoterpenoids were the most often found constituent in kinnow peel EO. Mehdizadeh et al. (2017) investigated how cumin EO quality was influenced by storage temperature. Cumin aldehyde (45.45-64.31%) increased during cumin oil storage, but lower boiling temperature components like β-pinene (1.57-10.03%) and p-cymene (14.93-24.9%) decreased at ambient temperatures.

Table 4: GC-MS analysis of 12-month stored essential oil extracted from kinnow peel (a) HD, (b) MAHD, (c) UAHD, (d) OHHD temperature 4 oC

| RT | Compound name | 12 months stored EO at temp 4 oC (Peak area) |

|||

| HD | UAHD | MAHD | OHHD | ||

| 6.28 | à-Pinene | 1.12 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| 6.39 | (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1. 1]hept-2-ene | 0.38 | 0.63 | ND | 0.48 |

| 7.13 | á-Myrcene | 1.03 | 1.21 | 1.47 | 1.12 |

| 7.36 | Octanal | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.22 |

| 7.87-7.91 | D-limonene | 87.06 | 84.90 | 85.61 | 84.12 |

| 9.11 | Linalool | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| 10.78 | 3-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, Terpinen-4-ol | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.45 |

| 11.02 | à-Terpineol | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.85 |

| 11.16 | Decanal | 1.50 | 1.61 | 1.46 | 1.86 |

| 11.56 | 2-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl), Carveol | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.80 |

| 15.03 | Dodecanal | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| 16.62 | Germacrene D | ND | 0.30 | ND | |

| 16.83 | à-Farnesene | 0.70 | 1.07 | 0.86 | 0.98 |

| 17.28 | 1-Isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,5, 6,8a-hexahydronaphthalene | 1.20 | 1.72 | 1.33 | 1.73 |

| 17.73 | Cyclohexanemethanol, 4-ethenyl-à,à,4-trimethyl-3-(1-methylethenyl)-, [1R-(1à,3à,4á)] | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| 19.19 | 2-Naphthalenemethanol, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydro-à,à,4a, 8-tetramethyl- | ND | ND | ND | 0.37 |

| 19.54 | 2-Naphthalenemethanol, decahydro-à,à,4a-trimethyl-8-met hylene | ND | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| 20.08 | 2,6,11-Dodecatrienal, 2,6-dimethyl-10-methylene | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.59 | 0.84 |

| 20.94 | 2,6,9,11-Dodecatetraenal, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, | 0.89 | 1.67 | 1.77 | 1.76 |

EO=Essential Oil; GC-MS=Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; ND=Not Detected; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; RT=Retention Time; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation

Additionally, the oil compositions altered the least, with Cuminum cyminum maintaining its fundamental value even at low temperatures. Compounds preserved in the dark exhibited modest content variations, which may be attributable to structural and reactivity changes. The major step involved oxidizing the oil's most labile components. Similar results regarding the chemical makeup of citrus EOs were examined by Michaelakis et al. (2009). The most prevalent component in the EOs extracted using HD from orange fruit peel (96.2%), lemon (74.3%), and bitter orange (96.7%) was limonene. Moreover, Ferhat et al. (2006) discovered that limonene was the most prominent component of EOs obtained from orange peels, with comparable relative quantities in both extraction methods of HD and Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction (SFME). Similarly, in the present study, limonene was identified as the major constituent of kinnow peel EO across different extraction methods, confirming its dominance in citrus-derived EOs by all extraction methods of HD, MAHD, UAHD, and OHHD. But its concentration varied significantly across extraction techniques. This variation can be attributed not only to the extraction method but also to factors such as the botanical variety, maturity stage of the fruit, geographical origin, storage conditions of the peel, and operational parameters like temperature and time during extraction. These variables can influence the degradation or volatilization of limonene, ultimately affecting its concentration in the final extract.

Table 5: GC-MS analysis of 12-month stored essential oil extracted from kinnow peel (a) HD, (b) MAHD, (c) UAHD, (d) OHHD temperature -10 oC

| RT | Compound name | 12 months stored EO at temp -10 oC (Peak area) |

|||

| HD | UAHD | MAHD | OHHD | ||

| 6.28 | à-Pinene | 1.35 | 1.31 | 0.63 | 0.49 |

| 6.39 | (1R)-2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo[3.1. 1]hept-2-ene | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.48 |

| 7.13 | á-Myrcene | 1.13 | 1.28 | 1.51 | 1.15 |

| 7.36 | Octanal | 0.69 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.23 |

| 7.42 | D-limonene | ||||

| 7.87-7.91 | D-limonene | 88.11 | 85.24 | 84.23 | 84.48 |

| 9.11 | Linalool | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.49 |

| 10.78 | 3-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, Terpinen-4-ol | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.32 |

| 11.02 | à-Terpineol | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.79 |

| 11.16 | Decanal | 1.53 | 1.39 | 1.80 | 1.43 |

| 11.56 | 2-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl), Carveol | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.64 | 1.04 |

| 15.03 | Dodecanal | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| 16.62 | Germacrene D | ND | ND | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| 16.83 | à-Farnesene |

| 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.41 | |||

| 17.28 | 1-Isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,5, 6,8a-hexahydronaphthalene | 1.44 | 2.61 | 1.82 | 1.89 |

| 17.73 | Cyclohexanemethanol, 4-ethenyl-à,à,4-trimethyl-3-(1-methylethenyl)-, [1R-(1à,3à,4á)] | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.62 |

| 19.19 | 2-Naphthalenemethanol, 1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydro-à,à,4a, 8-tetramethyl- | ND | 0.42 | ND | 0.57 |

| 19.54 | 2-Naphthalenemethanol, decahydro-à,à,4a-trimethyl-8-met hylene | ND | ND | 0.56 | 0.24 |

| 20.08 | 2,6,11-Dodecatrienal, 2,6-dimethyl-10-methylene | 0.6 | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.94 |

| 20.94 | 2,6,9,11-Dodecatetraenal, 2,6,10-trimethyl-, | 1.21 | 1.69 | 1.96 | 1.53 |

EO=Essential Oil; GC-MS=Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; HD=Hydrodistillation; MAHD=Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation; ND=Not Detected; OHHD=Ohmic Heating Assisted Hydrodistillation; RT=Retention Time; UAHD=Ultrasonic Assisted Hydrodistillation

A further investigation by Turek and Stintzing (2012) on four prominent EOs found that varied storage conditions can impact the quality of specific EOs. Rowshan et al. (2013) investigated the EO compositions of Thymus daenensis aerial parts throughout a variety of storage temperatures and durations. Low temperatures (-20 ◦C) resulted in minimal alterations to oil compositions, preserving their primary quality. In addition to terpinene (10.1-4.7%) and p-cymene (8.3-4.7%) as thymol and carvacrol precursors, the quantities of compounds with lower boiling temperatures, such as α pinene (4.3-0.5%), γ terpinene (1.8-0.5%), and myrcene (1-0.4%), were reduced at ambient temperatures.

The current study revealed a similar trend, where storage at sub-zero temperatures better preserved the chemical profile of kinnow peel EO, particularly maintaining higher concentrations of key volatile components compared to storage at 4 °C as shown in Table 4.

Conclusion

D–limonene was the predominant components in all extraction methods of citrus peel oils, with concentrations ranging from 85.12% to 92.04% depending on the extraction method. The antimicrobial study showed strong effects against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans, and A. niger, indicating that this EO could be a promising natural antimicrobial agent. Additionally, storing it at -10 °C helped maintain its chemical composition and biological activity better than storing it at 4 °C, as shown by the GC-MS analysis. These findings highlight its potential as a sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives, particularly for food storage applications. Further study is needed to assess the oil's constituent components and their efficiency against infections for possible use as natural preservatives.

Using EOs in their natural state can be tricky—they tend to evaporate easily, don’t mix well with water, and break down over time. To overcome these challenges and enhance their efficacy, turning them into nano-formulations is highly recommended. By encapsulating EOs in nano-sized carriers, we can make them more stable, easier to mix, and capable of releasing their active components more gradually. This not only strengthens their antimicrobial properties but also extend their functional longevity. Consequently, nano-encapsulated EOs represents a more practical and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic additives for applications in food preservation, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.

Author contributions

K.Y., M.K., and A.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, and analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Guru Jambheshwer University of Science and Technology, Hisar for providing the facilities and support required to conduct this research.

Conflict of interests

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

References

The current study revealed a similar trend, where storage at sub-zero temperatures better preserved the chemical profile of kinnow peel EO, particularly maintaining higher concentrations of key volatile components compared to storage at 4 °C as shown in Table 4.

Conclusion

D–limonene was the predominant components in all extraction methods of citrus peel oils, with concentrations ranging from 85.12% to 92.04% depending on the extraction method. The antimicrobial study showed strong effects against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans, and A. niger, indicating that this EO could be a promising natural antimicrobial agent. Additionally, storing it at -10 °C helped maintain its chemical composition and biological activity better than storing it at 4 °C, as shown by the GC-MS analysis. These findings highlight its potential as a sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives, particularly for food storage applications. Further study is needed to assess the oil's constituent components and their efficiency against infections for possible use as natural preservatives.

Using EOs in their natural state can be tricky—they tend to evaporate easily, don’t mix well with water, and break down over time. To overcome these challenges and enhance their efficacy, turning them into nano-formulations is highly recommended. By encapsulating EOs in nano-sized carriers, we can make them more stable, easier to mix, and capable of releasing their active components more gradually. This not only strengthens their antimicrobial properties but also extend their functional longevity. Consequently, nano-encapsulated EOs represents a more practical and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic additives for applications in food preservation, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.

Author contributions

K.Y., M.K., and A.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, and analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Guru Jambheshwer University of Science and Technology, Hisar for providing the facilities and support required to conduct this research.

Conflict of interests

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

References

Abbasi N., Ghaneialvar H., Moradi R., Zangeneh M.M., Zangeneh A. (2021). Formulation and characterization of a novel cutaneous wound healing ointment by silver nanoparticles containing Citrus lemon leaf: achemobiological study. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 14: 103246. [DOI: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103246]

Abdou A., Idouaarame S., Salah M., Nor N., Zahm S., El Makssoudi A., Mazoir N., Benharref A., Dari A., Eddine J.J., Blaghen M., Dakir M. (2022). Phytochemical study: molecular docking of eugenol derivatives as antioxidant and antimicrobial agents. Letters in Organic Chemistry. 19: 774–783. [DOI: 10.2174/1570178619666220111112125]

Achir M., Dakir M., El Makssoudi A., Belbachir A., Adly F., Blaghen M., El Amrani A., JamalEddine J. and Bettach N. (2022). Isolation, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of communic acid from Juniperusphoenicea. Journal of Complementary Integrative MedIcine. 19: 467-470. [DOI: 10.1515/jcim-2019-0319]

Agatonovic-Kustrin S., Ristivojevic P., Gegechkori V., Litvinova T.M., Morton D.W. (2020). Essential oil quality and purity evaluation via FT-IR spectroscopy and pattern recognition techniques. Applied Sciences. 10: 7294. [DOI: 10.3390 /app10207294]

Akbari S., Abdurahman N.H., Yunus R.M., Fayaz F. (2019). Microwave-assisted extraction of saponin, phenolic and flavonoid compounds from Trigonellafoenum-graecum seed based on two level factorial design. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. 14: 100212. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jarmap. 2019.100212]

Al-Hilphy A.R., Al-Mtury A.A.A., Al-Shatty S.M., Hussain Q.N., Gavahian M. (2022). Ohmic heating as a by-product valorization platform to extract oil from carp (Cyprinuscarpio) viscera. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 15: 2515-2530. [DOI: 10.1007/ s11947-022-02897-y]

Anwar T., Qureshi H., Fatima A., Sattar K., Albasher G., Kamal A., Ayaz A., Zaman W. (2023). Citrus sinensis peel oil extraction and evaluation as an antibacterial and antifungal agent. Microorganisms. 11: 1662. [DOI: 10.3390/ microorganisms 11071662]

Baritaux O., Richard H., Touche J., Derbesy M. (1992). Effects of drying and storage of herbs and spices on the essential oil. part I. basil: Ocimumbasilicum L. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 7: 267-271. [DOI: 10.1002/ffj.2730070507]