Volume 12, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025, 12(4): 263-270 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sabrinatami Z, Purwandari F, Utami T, Cahyanto M. Comparison of Acid Fermentation under Vacuum and by Conventional Method in Tempeh Production: Microbial and Chemical Changes. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025; 12 (4) :263-270

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1322-en.html

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1322-en.html

Department of Food and Agricultural Product Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Flora No. 1, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia , mn_cahyanto@ugm.ac.id

Full-Text [PDF 327 kb]

(59 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (62 Views)

Full-Text: (8 Views)

Comparison of Acid Fermentation under Vacuum and by Conventional Method in Tempeh Production: Microbial and Chemical Changes

Z. Sabrinatami, F.A. Purwandari, T. Utami, M.N. Cahyanto [*]*

Department of Food and Agricultural Product Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Flora No. 1, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia

HIGHLIGHTS

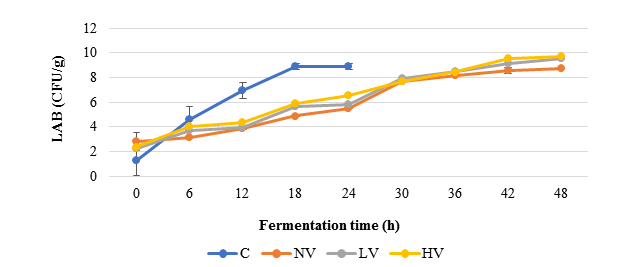

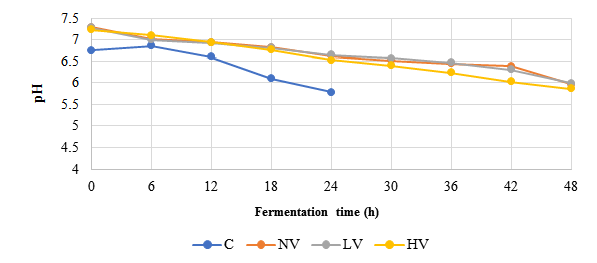

Figure 1: Changes of lactic acid bacteria during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; CFU=Colony-Forming Unit; HV=High Vacuum; LAB=Lactic Acid Bacteria; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

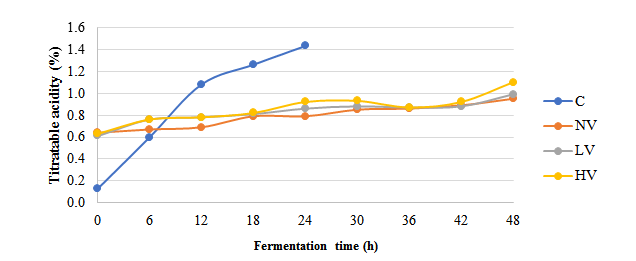

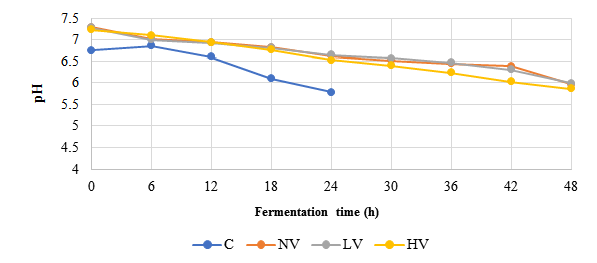

Figure 2: Changes of pH in soybeans during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; HV=High Vacuum; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

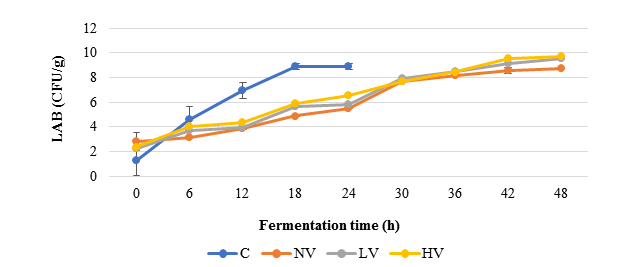

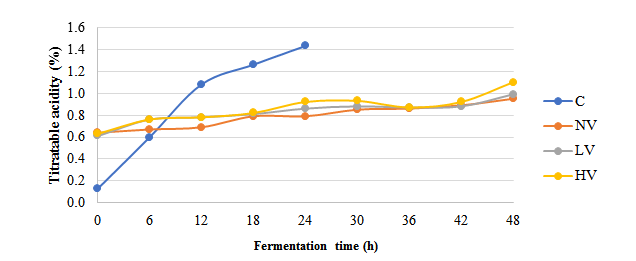

Figure 3: Changes of titratable acidity in soybeans during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; HV=High Vacuum; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

Z. Sabrinatami, F.A. Purwandari, T. Utami, M.N. Cahyanto [*]*

Department of Food and Agricultural Product Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Flora No. 1, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia

- Lactic acid bacteria growth was slower during acid fermentation under vacuum than in the conventional method.

- The pH decrease was also slower during acid fermentation under vacuum.

- The protein, phytic acid, and tannin contents of the beans significantly changed during the conventional acid fermentation method.

- The content of protein, phytic acid, and tannin did not significantly change during acid fermentation under vacuum.

- The trypsin inhibitor content did not change significantly during acid fermentation by either method.

| Article type Original article |

ABSTRACT Background: In conventional tempeh processing, water is required at most steps, including the acid fermentation by soaking. In this study, vacuum conditions during acid fermentation were employed instead of soaking soybeans to reduce the water requirement and wastewater generated. This study aimed to evaluate the microbial and chemical changes during acid fermentation under vacuum conditions. Methods: Tempeh processing started by hydrating peeled soybeans with water, followed by incubation under vacuum at pressure101.3, 60.7, and 19.2 kPa. Samples were taken every 6 h to analyse Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) growth, pH, and titratable acidity. Crude protein and anti-nutritional factors were analysed at the beginning and end of the fermentation. Results: LAB grew and reached the stationary phase after 48 h compared 18 h in the conventional methods. The pH of soybeans decreased to below 6.0 after 24 h and 48 h of acid fermentation by the conventional and vacuum methods, respectively. Titratable acidity increased during acid fermentation. Protein, phytic acid, and tannin contents changed significantly during conventional acid fermentation; however these compounds did not change significantly during acid fermentation under vacuum. Conclusion: Acid fermentation with vacuum methods showed potential for reducing anti-nutrients such as phytic acid and tannins in soybeans. Further optimization is required to improve LAB growth under vacuum conditions. © 2025, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |

|

| Keywords Tempeh Soybeans Fermentation Vacuum Bacteria, Anaerobic |

||

| Article history Received: 09 Jan 2025 Revised: 16 Nov 2025 Accepted: 20 Nov 2025 |

||

| Abbreviations CFU=Colony-Forming Unit HV=High Vacuum LAB=Lactic Acid Bacteria LV=Low Vacuum TA=Titratable Acidity TI=Trypsin Inhibitor TIA=Trypsin Inhibitor Activity |

To cite: Sabrinatami Z., Purwandari F.A., Utami T., Cahyanto M.N. (2025). Comparison of acid fermentation under vacuum and by conventional method in tempeh production: microbial and chemical changes. Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control. 12: 263-270.

Introduction

Introduction

Tempeh is an authentic Indonesian fermented food primarily produced from soybeans using Rhizopus sp. Tempeh is an affordable protein source with a nice flavor, sliceable meat-like texture, and excellent nutritional qualities (Shurtleff and Aoyagi, 2001) . Tempeh has become a popular and high-demand food leading to the expansion of the tempeh industry in Indonesia. The number of tempeh industries has reached 81 thousand with an annual production of 2.4 million tons (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2024) . Tempeh production involves various processing stages, including soaking, dehulling, flotation, soaking for acid fermentation, washing, boiling, cooling, and mold/fungal fermentation for 24-36 h at 30 °C or 48-72 h at 25 °C (Nout and Kiers, 2005) . Hasbullah and Silvy (2020) reported that water usage/consumption in the conventional method of tempeh production is 52.9 L per kg of soybeans. Meanwhile, daily production in the tempeh industry can produce up to 200 kg of soybeans, requiring more than 1.000 L of water. Production of tempeh requires quite high amounts of water and consequently produces a lot of wastewaters (Hasbullah and Silvy, 2020) . Wastewater primarily results from the water used for boiling, flotation of hulls, washing, and acid fermentation by soaking.

In the conventional method of tempeh production, acid fermentation is performed by the soaking of soybeans. Acid fermentation, typically conducted by soaking, is a critical step to acidify the soybeans for mold fermentation. The anaerobic conditions created by soaking promote the dominant growth of naturally occurring Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), which produce lactic acid and consequently lower the pH of the soybeans. Additionally, several organic acids such as valeric, citric, propionic, acetic acids, lactic acid, and malic acid in soybeans dissolve into the soaking water due to microbial activity, especially Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus faecium, and Staphylococcus epidermidis which contribute to lowering the pH during soaking(Mulyowidarso et al., 1991) . A decrease pH is correlated with high microbial growth, indicating a presence of microbial activity during soaking (Nurdini et al., 2015) Microbial activity during soaking is dominated by LAB, which is Lactobacillus by 98% (Radita et al., 2017) In addition, soaking eliminates anti-nutritional compounds such as phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors. Previous research reported a decrease of tannin and phytic acid content in black soybeans during soaking and natural fermentation for 24 h (Chauhan et al., 2022) , as well as a reduction in Trypsin Inhibitor (TI) content in dehulled soybeans during 12 h of soaking (Abu-Salem et al., 2014) Soaking for 12 h has also been reported to increase the crude protein content of lima beans due to microflora fermentation in the soaking water (Adebayo, 2014) .

To reduce water usage, we performed acid fermentation under anaerobic conditions using a vacuum method in the present study. The vacuum method removes trapped and dissolved gases within a specific container. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been reported on the use of vacuum method for acid fermentation. We hypothesize that different methods of acid fermentation can lead to varying changes in the nutritional and anti-nutritional content of soybeans. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the microbial and chemical changes during acid fermentation under vacuum conditions.

Materials and methods

In the conventional method of tempeh production, acid fermentation is performed by the soaking of soybeans. Acid fermentation, typically conducted by soaking, is a critical step to acidify the soybeans for mold fermentation. The anaerobic conditions created by soaking promote the dominant growth of naturally occurring Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), which produce lactic acid and consequently lower the pH of the soybeans. Additionally, several organic acids such as valeric, citric, propionic, acetic acids, lactic acid, and malic acid in soybeans dissolve into the soaking water due to microbial activity, especially Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus faecium, and Staphylococcus epidermidis which contribute to lowering the pH during soaking

To reduce water usage, we performed acid fermentation under anaerobic conditions using a vacuum method in the present study. The vacuum method removes trapped and dissolved gases within a specific container. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been reported on the use of vacuum method for acid fermentation. We hypothesize that different methods of acid fermentation can lead to varying changes in the nutritional and anti-nutritional content of soybeans. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the microbial and chemical changes during acid fermentation under vacuum conditions.

Materials and methods

Materials

Yellow soybean (Glycine max Merr.) Grobogan variety was purchased from PT. Java Agro Prima, Bantul, Yogyakarta. Commercial mold inoculum containing Rhizopus oligosporus (Raprima, Indonesia) was purchased from the local market (Toko Hasil Indah, Yogyakarta).

Tempeh processing methods

Tempeh was produced using the conventional methods following a previous report (Nout and Kiers, 2005) . First, 500 g of soybeans were sorted and soaked in tap water (1:3 w/v) for 90 min. Then, the soybeans were boiled for 30 min, mechanically dehulled using grinder (Bengkel Rekayasa Wangdi, Indonesia), and subjected to flotation to separate soybean seeds from the husks. Spontaneous acid fermentation was carried out subsequently by soaking soybeans in fresh water (1:2 w/v) for 24 h. After that, soybeans were rinsed three times and then boiled for 30 min. Then, they were drained, cooled to room temperature, and inoculated with tempeh starter culture (R. oligosporus). Soybeans were packed using a plastic bag and incubated on the table at room temperature (27-30 °C) for 36–48 h.

In tempeh production under vacuum conditions, 1 kg of soybeans was heated using a cabinet dryer (Bengkel Rekayasa Wangdi, Indonesia) at 65 °C for 2 h, then dehulled them using a grinder (Bengkel Rekayasa Wangdi, Indonesia), followed by separating soybean husks by air flow. Dehulled soybeans were hydrated with water at a ratio of 1:1.2 (w/v) for 2 h. Hydration time and water volume were determined based on preliminary research (1 kg soybean absorbed 1.2 L water after 2 h mixing). Subsequently, spontaneous acid fermentation was carried out by incubating hydrated soybeans under vacuum conditions for 48 h. The vacuum levels used in this study were non-vacuum (101.3 kPa), Low Vacuum (LV, 60.7 kPa), and High Vacuum (HV, 19.2 kPa). After acid fermentation, the soybeans were washed three times and boiled for 60 min. Then, they were drained, cooled to room temperature, and inoculated with the tempeh starter culture. Soybeans were packed using a plastic bag and incubated at room temperature (27-30 °C) for 48 h.

In tempeh production under vacuum conditions, 1 kg of soybeans was heated using a cabinet dryer (Bengkel Rekayasa Wangdi, Indonesia) at 65 °C for 2 h, then dehulled them using a grinder (Bengkel Rekayasa Wangdi, Indonesia), followed by separating soybean husks by air flow. Dehulled soybeans were hydrated with water at a ratio of 1:1.2 (w/v) for 2 h. Hydration time and water volume were determined based on preliminary research (1 kg soybean absorbed 1.2 L water after 2 h mixing). Subsequently, spontaneous acid fermentation was carried out by incubating hydrated soybeans under vacuum conditions for 48 h. The vacuum levels used in this study were non-vacuum (101.3 kPa), Low Vacuum (LV, 60.7 kPa), and High Vacuum (HV, 19.2 kPa). After acid fermentation, the soybeans were washed three times and boiled for 60 min. Then, they were drained, cooled to room temperature, and inoculated with the tempeh starter culture. Soybeans were packed using a plastic bag and incubated at room temperature (27-30 °C) for 48 h.

Sample preparation

Sampling was performed every 6 h during acid fermentation. Samples for microbial analysis were used immediately. For all other analyses, samples were first freeze-dried (Labconco, USA) at -40 °C for 32 h. The dried beans were then grinded using a blender (HR2115/00, Philips, Netherlands), sieved through a 425 μm sieve, packed in plastic pouches, and stored at 5 °C until analysis.

Analysis LAB

LAB growth was performed following a method in previous study (Yudianti et al. 2020). All fresh samples were diluted with sterile 0.85% NaCl (Supelco, Denmark) solution; then 1 ml of each sample were placed into petri dishes and poured with De Man–Rogosa–Sharpe agar (Oxoid Ltd, England). Plating was done in two replicates and incubated at 37 °C for 2 days. The number of LAB was quantified as Colony-Forming Units per gram (CFU/g) of sample.

Analysis of Titratable Acidity (TA)

TA was determined by titration with 0.1 M NaOH (Supelco, Germany) and expressed as lactic acid, while pH was measured using a pH meter (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) according to the methods of Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) 981.12 (Boland et al. 1981) .

Analysis of crude protein

Crude protein content was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method as described by Association of Official Analytical Chemists (Thiex et al., 2002).

Analysis of phytic acid

The phytic acid content was determined according to the method of Davies and Reid (1979) . Soybean powder were extracted in 0.5 M HNO3 (Supelco, Germany) for 3 h in a water bath shaker (Memmert, Germany) at 37 °C with moderate agitation.

Analysis of tannin

Tannin content was determined according to the method of Rangana (1977) . A 0.5 g sample was extracted with 40 ml of distilled water for 30 min in boiling water bath. A standard curve was prepared using tannic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, China), and the tannin content was expressed as mg of tannic acid per g of sample.

Analysis of TI

TI was measured by the method described by Kakade et al. (1974) , using benzoyl-Dl-arginine-nitroanilide hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, China) as a substrate solution.

Statistical analysis

LAB, pH, TA, crude protein, phytic acid, tannin, and TI were subjected to a one-way ANOVA with a 95% confidence level. Significantly different means at p<0.05 were identified using Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) as a post-hoc analysis.

Results and discussion

Growth of LAB

Figure 1 shows LAB changes at different acid fermentation under vacuum conditions compared to the conventional method.

Figure 1: Changes of lactic acid bacteria during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; CFU=Colony-Forming Unit; HV=High Vacuum; LAB=Lactic Acid Bacteria; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

An increase of LAB was observed in all acid fermentation methods (Figure 1). LAB populations showed a rapid increase in the first 18 h of fermentation. The conventional method showed significantly faster LAB growth compared to vacuum methods, with stationary phase achieved in 18 h compared to 48 h, respectively. The final LAB counts in the LV and HV methods were significantly higher than those in the non-vacuum method (p<0.05).

Previous research has similarly observed LAB growth during 18 h of acid fermentation from 4 log CFU/g to 6 log CFU/g(Efriwati et al., 2013) . The microbial increase during fermentation may be due to the availability of nutrients released from the cotyledons during fermentation and the utilization of some nutrients as a growth substrate by the fermenting organisms (Omodara and Aderibigbe, 2019). The acid fermentation with vacuum conditions showed lower LAB growth compared to the conventional method. LAB’s ability during acid fermentation is affected by the medium of fermentation, such as water. The environmental conditions and availability of nutrients that dissolve into the soaking water in the conventional method facilitated the rapid growth of LAB. We also observed that at the beginning of fermentation, different LAB counts were observed. The difference in LAB counts at the beginning of fermentation could be due to variations in pre-fermentation treatments, such as boiling, which eliminates species responsible for acid fermentation (Mulyowidarso et al., 1989)

Previous research has similarly observed LAB growth during 18 h of acid fermentation from 4 log CFU/g to 6 log CFU/g

.

pH and TA

The effect of different acid fermentation methods on pH and TA is presented in Figure 2. All methods demonstrated a consistent pattern of pH reduction and TA increase during acid fermentation. The conventional method exhibited a more rapid pH reduction compared to non-vacuum, LV, and HV methods, reaching 5.78±0.08 within 24 h, while vacuum methods showed slower reduction, with final pH values ranging from 5.86±0.04 to 5.99±0.03. This pH decrease was confirmed by an increase in TA, particularly in the conventional method, which achieved the highest TA value (1.43±0.04). Comparatively, TA in the non-vacuum, LV, and HV methods were increased at slower rate, with final values between 0.95±0.03 and 1.10±0.04 (Figure 3). These findings highlight the distinct acidification kinetics between conventional and vacuum fermentation methods.

pH and TA

The effect of different acid fermentation methods on pH and TA is presented in Figure 2. All methods demonstrated a consistent pattern of pH reduction and TA increase during acid fermentation. The conventional method exhibited a more rapid pH reduction compared to non-vacuum, LV, and HV methods, reaching 5.78±0.08 within 24 h, while vacuum methods showed slower reduction, with final pH values ranging from 5.86±0.04 to 5.99±0.03. This pH decrease was confirmed by an increase in TA, particularly in the conventional method, which achieved the highest TA value (1.43±0.04). Comparatively, TA in the non-vacuum, LV, and HV methods were increased at slower rate, with final values between 0.95±0.03 and 1.10±0.04 (Figure 3). These findings highlight the distinct acidification kinetics between conventional and vacuum fermentation methods.

Figure 2: Changes of pH in soybeans during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; HV=High Vacuum; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

Figure 3: Changes of titratable acidity in soybeans during acid fermentation

C=Conventional; HV=High Vacuum; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

LAB metabolism during fermentation leads to the production of a various acids, thus increasing TA and decreasing pH value. Previous studies (Chinma et al., 2020) have reported a correlation between pH reduction and increased acidity during fermentation due to the production of lactic acid, as a result of microbial degradation of carbohydrates and other nutrients, leading to the formation of organic acids that elevate acidity. The accumulation of organic acids, including acetic acid, due to the activity of fermentative organisms such as LAB and yeasts, contributes to the observed trend of decreasing pH and increasing TA (Obadina et al., 2013) . These findings are consistent with Pranoto et al., (2013)

Changes of protein and antinutritional factors during acid fermentation

The effect of acid fermentation methods on the crude protein, phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors of soybeans compounds is presented in Table 1.

, who reported a simultaneous decrease in pH and increase in TA during fermentation.

Table 1: Changes of the crude protein, phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors of soybeans during various acid fermentation methods

| Compound | Processing | Treatment | |||

| C | NV | LV | HV | ||

| Crude Protein (% Protein d.b) |

Pre AF | 40.45±0.79 a | 39.01±0.37 a | 39.40±0.93 a | 39.13±0.59 a |

| Post AF | 42.73±0.62 b | 39.44±0.27 a | 40.72±0.73 a | 39.89±0.51 a | |

| Phytic acid (mg Na Phytic/g) |

Pre AF | 1.64±0.01 a | 1.57±0.04 a | 1.66±0.04 a | 1.69±0.10 a |

| Post AF | 1.46±0.06 b | 1.52±0.12 a | 1.63±0.08 a | 1.66±0.05 a | |

| Total Tannins (mg tannic acid/g) |

Pre AF | 0.35±0.00 a | 0.49±0.08 a | 0.58±0.03 a | 0.55±0.00 a |

| Post AF | 0.16±0.03 b | 0.39±0.13 a | 0.46±0.03 b | 0.39±0.08 b | |

| Trypsin inhibitors (TIU/mg) |

Pre AF | 3.24±0.14 a | 3.34±0.03 a | 3.30±0.03 a | 3.35±0.07 a |

| Post AF | 3.12±0.02 a | 3.23±0.06 a | 3.22±0.06 a | 3.21±0.11 a | |

Different lowercase letters indicate significant difference between samples in the same columns (p<0.05)

AF=Acid Fermentation; C=Conventional; C=Conventional; HV=High Vacuum; LV=Low Vacuum; NV=Non-Vacuum

Soybeans contain several nutritional compounds such as protein and anti-nutritional compounds such as phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors. These compounds can be affected by various tempeh processing such as heat treatment (boiling or roasting), soaking, and fermentation. The conventional method showed a significant increase in crude protein compared to other methods (Table 1). The highest increase was shown in the conventional method with a final value of 42.73% protein dry basis (db). According to Cui et al. (2012) , the increase in crude protein in soybeans may result from microbial activity using carbohydrates as an energy source (substrate), leading to producing carbon dioxide as a by-product. The nitrogen in the fermented product becomes concentrated, thereby increasing the mass percentage of protein. Similarly, Adebayo, (2014) reported a rise in protein content in lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) after 12 h of soaking fermentation, attributing it to the activity of microflora in the soaking water. This increase in protein may be due to the biosynthesis of proteins in the form of amino acids by endogenous or exogenous enzymes or due to the growth of microorganisms during fermentation (Kohli and Singha, 2024) .

Furthermore, acid fermentation can reduce the content of phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors in soybeans (Table 1). The phytic acid content in the conventional method demonstrated a significantly greater reduction compared to the other methods, with a final value of 1.46 mg Na phytate/g after 24 h of fermentation. Previous studies have shown that soaking soybeans for 48 h leads to a reduction in phytic acid, likely due to its leaching into the soaking water(Adebayo, 2014) . This reduction is also influenced by the activation of endogenous phytase enzymes during soaking (Hendek Ertop and Bektaş, 2018) . In another study, LAB produced phytase that further hydrolyzed phytic acid under low pH conditions, reducing its content in the fermented product (Reale et al., 2007) . In a study by Adeyemo and Onilude (2013), over 5 days of fermentation with Lactobacillus plantarum significantly lowered phytic acid levels from 1.16 mg/g to 0.047 mg/g. In this study, vacuum conditions for acid fermentation method did not reduce the phytic acid content because the absence of water prevented the compounds from leaching out.

Acid fermentation reduced the tannin content of soybeans in all methods except for non-vacuum, which showed no significant change. The starting material of soybean before the acid fermentation of the conventional method had a significantly lower content compared to the pre-acid fermentation from other treatments. A decrease in tannins was observed in the conventional, LV, and HV methods (Table 1). Several studies reported a reduction in tannin content during fermentation due to leaching into the soaking water(Adebayo, 2014) and the presence of microbial activity (Adeyemo and Onilude, 2013). This reduction may result from enzymes produced by microbes, such as L. plantarum, which can break down and degrade anti-nutritional compounds into smaller units (Adeyemo and Onilude, 2013). L. plantarum has been reported to produce tannase enzyme after 24 h of growth under optimal conditions of 37 °C and pH 6 (Ayed and Hamdi, 2002) . The breakdown of polyphenols by microorganisms could further contribute to tannin reduction during fermentation (Worku and Sahu, 2017). It can be concluded that due to the absence of soaking water, microbial activity was playing a major role in the decrease of tannins in acid fermentation with vacuum conditions.

None of the acid fermentation methods caused a significant decrease of Trypsin Inhibitor Activity (TIA). The TIA was similar in both pre-acid fermentation and post-acid fermentation in all treatments. This study did not show a significant reduction in TIA in soybeans. TIA can decrease due to soaking and bacterial activity(Avilés-Gaxiola et al., 2018) , and heat treatments such as boiling, roasting, or microwaving can significantly reduce TIA (Yang et al., 2014) . However, the absence of a TIA reduction in this study suggests that the soaking during acid fermentation in conventional method or microbial activity under the tested conditions were insufficient to lower TIA. Since the compound responsible for TIA is a protein (Voss et al., 1996), the data suggested that the protein might not be easily dissolved during soaking and the LAB involved in the acid fermentation did not produce enough proteases to degrade the protein.

It would be interesting to investigate the organoleptic properties of tempeh produced by these different methods to determine if a specific production method imparts unique organoleptic properties of the tempeh produced. However, the organoleptic properties of tempeh produced with different methods were not analysed in this study.

Furthermore, acid fermentation can reduce the content of phytic acid, tannins, and trypsin inhibitors in soybeans (Table 1). The phytic acid content in the conventional method demonstrated a significantly greater reduction compared to the other methods, with a final value of 1.46 mg Na phytate/g after 24 h of fermentation. Previous studies have shown that soaking soybeans for 48 h leads to a reduction in phytic acid, likely due to its leaching into the soaking water

Acid fermentation reduced the tannin content of soybeans in all methods except for non-vacuum, which showed no significant change. The starting material of soybean before the acid fermentation of the conventional method had a significantly lower content compared to the pre-acid fermentation from other treatments. A decrease in tannins was observed in the conventional, LV, and HV methods (Table 1). Several studies reported a reduction in tannin content during fermentation due to leaching into the soaking water

None of the acid fermentation methods caused a significant decrease of Trypsin Inhibitor Activity (TIA). The TIA was similar in both pre-acid fermentation and post-acid fermentation in all treatments. This study did not show a significant reduction in TIA in soybeans. TIA can decrease due to soaking and bacterial activity

It would be interesting to investigate the organoleptic properties of tempeh produced by these different methods to determine if a specific production method imparts unique organoleptic properties of the tempeh produced. However, the organoleptic properties of tempeh produced with different methods were not analysed in this study.

Conclusion

Acid fermentation, across all methods, successfully increased LAB growth while concurrently lowering pH and increasing TA. However, the conventional method yielded a greater increase in crude protein and a smaller reduction in anti-nutritional factors than the vacuum or non-vacuum methods. This suggests that acid fermentation under vacuum conditions holds significant potential for reducing anti-nutrients, such as phytic acid and tannins, in soybeans. The observed significant differences between the conventional and vacuum-based methods highlight a distinct effect of the fermentation environment. To utilize this potential, further optimization is required to enhance LAB growth especially under vacuum conditions, such as the use of wastewater from washing acidified soybeans as LAB inoculant or from boiling acidified soybeans as nutrient sources for LAB growth.

Author contributions

Z.S. conducted the experimental work, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript; F.A.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript; T.U. supervised the research and reviewed the manuscript; M.N.C. contributed in designing the research and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the laboratory staff members of the Department of Food and Agricultural Product Technology for the technical assistance provided during this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

References

Abu-Salem F.M., Mohamed R.K., Gibriel A.Y., Rasmy N.M.H. (2014). Levels of some antinutritional factors in tempeh produced from some legumes and jojobas seeds. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Engineering. 8: 296-301. [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1093040]

Adebayo S.F. (2014). Effect of soaking time on the proximate, mineral compositions and anti-nutritional factors of lima bean. Food Science and Quality Management. 27: 1-3.

Adeyemo S.M., Onilude A.A. (2013). Enzymatic reduction of anti-nutritional factors in fermenting soybeans by Lactobacillus plantarum isolates from fermenting cereals. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 84-90. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30080-1]

Avilés-Gaxiola S., Chuck-Hernández C., Serna Saldívar S.O. (2018). Inactivation methods of trypsin inhibitor in legumes: a review. Journal of Food Science. 83: 17-29. [DOI: 10.1111/ 1750-3841.13985]

Ayed L., Hamdi M. (2002). Culture conditions of tannase production by Lactobacillus plantarum. Biotechnology Letters. 24: 1763–1765. [DOI: 10.1023/A:1020696801584]

Boland F.E., Lin R.C., Mulvaney T.R., Mcclure F.D., Johnston M.R. (1981). pH determination in acidified foods: collaborative study. Journal of the AOAC International. 64: 332-336. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/64.2.332]

BPS-Statistics Indonesia (2024). Statistical yearbook of Indonesia 2024. Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, Indonesia. 52. URL: https://pst.bps.go.id.

Chauhan D., Kumar K., Ahmed N., Thakur P., Rizvi Q.U.E.H., Jan S., Yadav A.N. (2022). Impact of soaking, germination, fermentation, and roasting treatments on nutritional, anti-nutritional, and bioactive composition of black soybean (Glycine max L.). Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology. 10: 186-192. [DOI: 10.7324/JABB.2022.100523]

Chinma C.E., Azeez S.O., Sulayman H.T., Alhassan K., Alozie S.N., Gbadamosi H.D., Danbaba N., Oboh H.A., Anuonye J.C., Adebo O.A. (2020). Evaluation of fermented African yam bean flour composition and influence of substitution levels on properties of wheat bread. Journal of Food Science. 85: 4281-4289. [DOI: 10.1111/1750-3841.15527]

Cui L., Li D.J., Liu C.Q. (2012). Effect of fermentation on the nutritive value of maize. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 47: 755-760. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621. 2011.02904.x]

Davies N.T., Reid H. (1979). An evaluation of the phytate, zinc, copper, iron and manganese contents of, and Zn availability from soya based textured-vegetable-protein meat-substitutes or meat-extenders. British Journal of Nutrition. 41: 579-589. [DOI: 10.1079/bjn19790073]

Efriwati, Suwanto A., Rahayu G., Nuraida L. (2013). Population dynamics of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) during tempeh production. Hayati Journal of Biosciences. 20: 57-64. [DOI: 10.4308/hjb.20.2.57]

Hasbullah, Silvy D. (2020). Study of tempe production from dried peeled soybeans. IOP conference series: earth and environmental science. 515: 012059. [DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/515/1/012059]

Hendek Ertop M., Bektaş M. (2018). Enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients and reduction of antinutrients in foods with some processes. Food and Health. 4: 159-165. [DOI: 10.3153/ fh18016]

Kakade M.L., Rackis J.J., McGhee J.E., Puski G. (1974). Determination of trypsin inhibitor activity of soy products: a collaborative analysis of an improved procedure. Cereal Chemistry. 51: 376-382.

Kohli V., Singha S. (2024). Protein digestibility of soybean: how processing affects seed structure, protein and non-protein components. Discover Food. 4. [DOI: 10.1007/s44187-024-00076-w]

Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1989). The microbial ecology of soybean soaking for tempe production. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 8: 35-46. [DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(89)90078-0]

Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1991). Changes in the concentration of organic acids during the soaking of soybeans for tempe production. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 26: 595-606. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb02005.x]

Nout M.J.R., Kiers J.L. (2005). Tempe fermentation, innovation and functionality: update into the third millenium. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 98: 789-805. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2672. 2004.02471.x]

Nurdini A.L., Nuraida L., Suwanto A., Suliantari (2015). Microbial growth dynamics during tempe fermentation in two different home industries. International Food Research Journal. 22: 1668-1674.

Obadina A.O., Akinola O.J., Shittu T.A., Bakare H.A. (2013). Effect of natural fermentation on the chemical and nutritional composition of fermented soymilk nono. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 91-97. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30081-3]

Omodara T.R., Aderibigbe E.Y. (2019). Comparative studies on the effect of fermentation on the nutritional compositions and anti-nutritional levels of Glycine max fermented products: tempeh and soy-iru. Annual Research and Review in Biology. 32: 1-9. [DOI: 10.9734/arrb/2019/v32i430094]

Pranoto Y., Anggrahini S., Efendi Z. (2013). Effect of natural and Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation on in-vitro protein and starch digestibilities of sorghum flour. Food Bioscience. 2: 46-52. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fbio.2013.04.001]

Radita R., Suwanto A., Kurosawa N., Wahyudi A.T., Rusmana I. (2017). Metagenome analysis of tempeh production: where did the bacterial community in tempeh come from? Malaysian Journal of Microbiology. 13: 280-288. [DOI: 10.21161/ mjm.101417]

Ranganna S. (1977). Manual of analysis of fruit and vegetable products. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New Delhi, India. pp: 69.

Reale A., Konietzny U., Coppola R., Sorrentino E., Greiner R. (2007). The importance of lactic acid bacteria for phytate degradation during cereal dough fermentation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55: 2993-2997. [DOI: 10.1021/jf063507n]

Shurtleff W., Aoyagi A. (2001). The book of tempeh. 2nd edition. Ten Speed Press, California, The United States of America. pp: 8.

Thiex N.J., Manson H., Anderson S., Persson J. (2002). Determination of crude protein in animal feed, forage, grain, and oilseeds by using block digestion with a copper catalyst and steam distillation into boric acid: collaborative study. Journal of AOAC International. 85: 309–317. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/85.2.309]

Voss R.H., Ermler U., Essen L.O., Wenzl G., Kim Y.M., Flecker P. (1996). Crystal structure of the bifunctional soybean Bowman-Birk inhibitor at 0.28-nm resolution. European Journal of Biochemistry. 242: 122-131. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1432-1033. 1996.0122r.x]

Worku A., Sahu O. (2017). Significance of fermentation process on biochemical properties of Phaseolus vulgaris (red beans). Biotechnology Reports. 16: 5-11. [DOI: 10.1016/ j.btre.2017.09.001]

Yang H.W., Hsu C.K., Yang Y.F. (2014). Effect of thermal treatments on anti-nutritional factors and antioxidant capabilities in yellow soybeans and green-cotyledon small black soybeans. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 94: 1794-1801. [DOI: 10.1002/jsfa.6494]

Yudianti N.F., Yanti R., Cahyanto M.N., Rahayu E.S., Utami T. (2020). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from legume soaking water of tempeh productions. Digital Press Life Sciences. 2: 00003. [DOI: 10.29037/digitalpress.22328]

Adebayo S.F. (2014). Effect of soaking time on the proximate, mineral compositions and anti-nutritional factors of lima bean. Food Science and Quality Management. 27: 1-3.

Adeyemo S.M., Onilude A.A. (2013). Enzymatic reduction of anti-nutritional factors in fermenting soybeans by Lactobacillus plantarum isolates from fermenting cereals. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 84-90. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30080-1]

Avilés-Gaxiola S., Chuck-Hernández C., Serna Saldívar S.O. (2018). Inactivation methods of trypsin inhibitor in legumes: a review. Journal of Food Science. 83: 17-29. [DOI: 10.1111/ 1750-3841.13985]

Ayed L., Hamdi M. (2002). Culture conditions of tannase production by Lactobacillus plantarum. Biotechnology Letters. 24: 1763–1765. [DOI: 10.1023/A:1020696801584]

Boland F.E., Lin R.C., Mulvaney T.R., Mcclure F.D., Johnston M.R. (1981). pH determination in acidified foods: collaborative study. Journal of the AOAC International. 64: 332-336. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/64.2.332]

BPS-Statistics Indonesia (2024). Statistical yearbook of Indonesia 2024. Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, Indonesia. 52. URL: https://pst.bps.go.id.

Chauhan D., Kumar K., Ahmed N., Thakur P., Rizvi Q.U.E.H., Jan S., Yadav A.N. (2022). Impact of soaking, germination, fermentation, and roasting treatments on nutritional, anti-nutritional, and bioactive composition of black soybean (Glycine max L.). Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology. 10: 186-192. [DOI: 10.7324/JABB.2022.100523]

Chinma C.E., Azeez S.O., Sulayman H.T., Alhassan K., Alozie S.N., Gbadamosi H.D., Danbaba N., Oboh H.A., Anuonye J.C., Adebo O.A. (2020). Evaluation of fermented African yam bean flour composition and influence of substitution levels on properties of wheat bread. Journal of Food Science. 85: 4281-4289. [DOI: 10.1111/1750-3841.15527]

Cui L., Li D.J., Liu C.Q. (2012). Effect of fermentation on the nutritive value of maize. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 47: 755-760. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621. 2011.02904.x]

Davies N.T., Reid H. (1979). An evaluation of the phytate, zinc, copper, iron and manganese contents of, and Zn availability from soya based textured-vegetable-protein meat-substitutes or meat-extenders. British Journal of Nutrition. 41: 579-589. [DOI: 10.1079/bjn19790073]

Efriwati, Suwanto A., Rahayu G., Nuraida L. (2013). Population dynamics of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) during tempeh production. Hayati Journal of Biosciences. 20: 57-64. [DOI: 10.4308/hjb.20.2.57]

Hasbullah, Silvy D. (2020). Study of tempe production from dried peeled soybeans. IOP conference series: earth and environmental science. 515: 012059. [DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/515/1/012059]

Hendek Ertop M., Bektaş M. (2018). Enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients and reduction of antinutrients in foods with some processes. Food and Health. 4: 159-165. [DOI: 10.3153/ fh18016]

Kakade M.L., Rackis J.J., McGhee J.E., Puski G. (1974). Determination of trypsin inhibitor activity of soy products: a collaborative analysis of an improved procedure. Cereal Chemistry. 51: 376-382.

Kohli V., Singha S. (2024). Protein digestibility of soybean: how processing affects seed structure, protein and non-protein components. Discover Food. 4. [DOI: 10.1007/s44187-024-00076-w]

Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1989). The microbial ecology of soybean soaking for tempe production. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 8: 35-46. [DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(89)90078-0]

Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1991). Changes in the concentration of organic acids during the soaking of soybeans for tempe production. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 26: 595-606. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb02005.x]

Nout M.J.R., Kiers J.L. (2005). Tempe fermentation, innovation and functionality: update into the third millenium. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 98: 789-805. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2672. 2004.02471.x]

Nurdini A.L., Nuraida L., Suwanto A., Suliantari (2015). Microbial growth dynamics during tempe fermentation in two different home industries. International Food Research Journal. 22: 1668-1674.

Obadina A.O., Akinola O.J., Shittu T.A., Bakare H.A. (2013). Effect of natural fermentation on the chemical and nutritional composition of fermented soymilk nono. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 91-97. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30081-3]

Omodara T.R., Aderibigbe E.Y. (2019). Comparative studies on the effect of fermentation on the nutritional compositions and anti-nutritional levels of Glycine max fermented products: tempeh and soy-iru. Annual Research and Review in Biology. 32: 1-9. [DOI: 10.9734/arrb/2019/v32i430094]

Pranoto Y., Anggrahini S., Efendi Z. (2013). Effect of natural and Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation on in-vitro protein and starch digestibilities of sorghum flour. Food Bioscience. 2: 46-52. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fbio.2013.04.001]

Radita R., Suwanto A., Kurosawa N., Wahyudi A.T., Rusmana I. (2017). Metagenome analysis of tempeh production: where did the bacterial community in tempeh come from? Malaysian Journal of Microbiology. 13: 280-288. [DOI: 10.21161/ mjm.101417]

Ranganna S. (1977). Manual of analysis of fruit and vegetable products. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New Delhi, India. pp: 69.

Reale A., Konietzny U., Coppola R., Sorrentino E., Greiner R. (2007). The importance of lactic acid bacteria for phytate degradation during cereal dough fermentation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55: 2993-2997. [DOI: 10.1021/jf063507n]

Shurtleff W., Aoyagi A. (2001). The book of tempeh. 2nd edition. Ten Speed Press, California, The United States of America. pp: 8.

Thiex N.J., Manson H., Anderson S., Persson J. (2002). Determination of crude protein in animal feed, forage, grain, and oilseeds by using block digestion with a copper catalyst and steam distillation into boric acid: collaborative study. Journal of AOAC International. 85: 309–317. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/85.2.309]

Voss R.H., Ermler U., Essen L.O., Wenzl G., Kim Y.M., Flecker P. (1996). Crystal structure of the bifunctional soybean Bowman-Birk inhibitor at 0.28-nm resolution. European Journal of Biochemistry. 242: 122-131. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1432-1033. 1996.0122r.x]

Worku A., Sahu O. (2017). Significance of fermentation process on biochemical properties of Phaseolus vulgaris (red beans). Biotechnology Reports. 16: 5-11. [DOI: 10.1016/ j.btre.2017.09.001]

Yang H.W., Hsu C.K., Yang Y.F. (2014). Effect of thermal treatments on anti-nutritional factors and antioxidant capabilities in yellow soybeans and green-cotyledon small black soybeans. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 94: 1794-1801. [DOI: 10.1002/jsfa.6494]

Yudianti N.F., Yanti R., Cahyanto M.N., Rahayu E.S., Utami T. (2020). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from legume soaking water of tempeh productions. Digital Press Life Sciences. 2: 00003. [DOI: 10.29037/digitalpress.22328]

[*] Corresponding author (M.N. Cahyanto)

Email: mn_cahyanto@ugm.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1448-876X

Email: mn_cahyanto@ugm.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1448-876X

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Special

Received: 25/01/09 | Accepted: 25/11/20 | Published: 25/12/21

Received: 25/01/09 | Accepted: 25/11/20 | Published: 25/12/21

References

1. Abu-Salem F.M., Mohamed R.K., Gibriel A.Y., Rasmy N.M.H. (2014). Levels of some antinutritional factors in tempeh produced from some legumes and jojobas seeds. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Engineering. 8: 296-301. [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1093040] [[DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1093040]]

2. Adebayo S.F. (2014). Effect of soaking time on the proximate, mineral compositions and anti-nutritional factors of lima bean. Food Science and Quality Management. 27: 1-3.

3. Adeyemo S.M., Onilude A.A. (2013). Enzymatic reduction of anti-nutritional factors in fermenting soybeans by Lactobacillus plantarum isolates from fermenting cereals. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 84-90. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30080-1] [DOI:10.1016/S0189-7241(15)30080-1]

4. Avilés-Gaxiola S., Chuck-Hernández C., Serna Saldívar S.O. (2018). Inactivation methods of trypsin inhibitor in legumes: a review. Journal of Food Science. 83: 17-29. [DOI: 10.1111/ 1750-3841.13985] [DOI:10.1111/1750-3841.13985] [PMID]

5. Ayed L., Hamdi M. (2002). Culture conditions of tannase production by Lactobacillus plantarum. Biotechnology Letters. 24: 1763-1765. [DOI: 10.1023/A:1020696801584] [DOI:10.1023/A:1020696801584]

6. Boland F.E., Lin R.C., Mulvaney T.R., Mcclure F.D., Johnston M.R. (1981). pH determination in acidified foods: collaborative study. Journal of the AOAC International. 64: 332-336. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/64.2.332] [DOI:10.1093/jaoac/64.2.332]

7. BPS-Statistics Indonesia (2024). Statistical yearbook of Indonesia 2024. Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, Indonesia. 52. URL: https://pst.bps.go.id.

8. Chauhan D., Kumar K., Ahmed N., Thakur P., Rizvi Q.U.E.H., Jan S., Yadav A.N. (2022). Impact of soaking, germination, fermentation, and roasting treatments on nutritional, anti-nutritional, and bioactive composition of black soybean (Glycine max L.). Journal of Applied Biology and Biotechnology. 10: 186-192. [DOI: 10.7324/JABB.2022.100523] [DOI:10.7324/JABB.2022.100523]

9. Chinma C.E., Azeez S.O., Sulayman H.T., Alhassan K., Alozie S.N., Gbadamosi H.D., Danbaba N., Oboh H.A., Anuonye J.C., Adebo O.A. (2020). Evaluation of fermented African yam bean flour composition and influence of substitution levels on properties of wheat bread. Journal of Food Science. 85: 4281-4289. [DOI: 10.1111/1750-3841.15527] [DOI:10.1111/1750-3841.15527] [PMID]

10. Cui L., Li D.J., Liu C.Q. (2012). Effect of fermentation on the nutritive value of maize. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 47: 755-760. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621. 2011.02904.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02904.x]

11. Davies N.T., Reid H. (1979). An evaluation of the phytate, zinc, copper, iron and manganese contents of, and Zn availability from soya based textured-vegetable-protein meat-substitutes or meat-extenders. British Journal of Nutrition. 41: 579-589. [DOI: 10.1079/bjn19790073] [DOI:10.1079/BJN19790073] [PMID]

12. Efriwati, Suwanto A., Rahayu G., Nuraida L. (2013). Population dynamics of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) during tempeh production. Hayati Journal of Biosciences. 20: 57-64. [DOI: 10.4308/hjb.20.2.57] [DOI:10.4308/hjb.20.2.57]

13. Hasbullah, Silvy D. (2020). Study of tempe production from dried peeled soybeans. IOP conference series: earth and environmental science. 515: 012059. [DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/515/1/012059] [DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/515/1/012059]

14. Hendek Ertop M., Bektaş M. (2018). Enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients and reduction of antinutrients in foods with some processes. Food and Health. 4: 159-165. [DOI: 10.3153/ fh18016] [DOI:10.3153/FH18016]

15. Kakade M.L., Rackis J.J., McGhee J.E., Puski G. (1974). Determination of trypsin inhibitor activity of soy products: a collaborative analysis of an improved procedure. Cereal Chemistry. 51: 376-382.

16. Kohli V., Singha S. (2024). Protein digestibility of soybean: how processing affects seed structure, protein and non-protein components. Discover Food. 4. [DOI: 10.1007/s44187-024-00076-w] [DOI:10.1007/s44187-024-00076-w]

17. Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1989). The microbial ecology of soybean soaking for tempe production. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 8: 35-46. [DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(89)90078-0] [DOI:10.1016/0168-1605(89)90078-0] [PMID]

18. Mulyowidarso R.K., Fleet G.H., Buckle K.A. (1991). Changes in the concentration of organic acids during the soaking of soybeans for tempe production. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 26: 595-606. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb02005.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb02005.x]

19. Nout M.J.R., Kiers J.L. (2005). Tempe fermentation, innovation and functionality: update into the third millenium. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 98: 789-805. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2672. 2004.02471.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02471.x] [PMID]

20. Nurdini A.L., Nuraida L., Suwanto A., Suliantari (2015). Microbial growth dynamics during tempe fermentation in two different home industries. International Food Research Journal. 22: 1668-1674.

21. Obadina A.O., Akinola O.J., Shittu T.A., Bakare H.A. (2013). Effect of natural fermentation on the chemical and nutritional composition of fermented soymilk nono. Nigerian Food Journal. 31: 91-97. [DOI: 10.1016/s0189-7241(15)30081-3] [DOI:10.1016/S0189-7241(15)30081-3]

22. Omodara T.R., Aderibigbe E.Y. (2019). Comparative studies on the effect of fermentation on the nutritional compositions and anti-nutritional levels of Glycine max fermented products: tempeh and soy-iru. Annual Research and Review in Biology. 32: 1-9. [DOI: 10.9734/arrb/2019/v32i430094] [DOI:10.9734/arrb/2019/v32i430094]

23. Pranoto Y., Anggrahini S., Efendi Z. (2013). Effect of natural and Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation on in-vitro protein and starch digestibilities of sorghum flour. Food Bioscience. 2: 46-52. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fbio.2013.04.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.fbio.2013.04.001]

24. Radita R., Suwanto A., Kurosawa N., Wahyudi A.T., Rusmana I. (2017). Metagenome analysis of tempeh production: where did the bacterial community in tempeh come from? Malaysian Journal of Microbiology. 13: 280-288. [DOI: 10.21161/ mjm.101417] [DOI:10.21161/mjm.101417]

25. Ranganna S. (1977). Manual of analysis of fruit and vegetable products. Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New Delhi, India. pp: 69.

26. Reale A., Konietzny U., Coppola R., Sorrentino E., Greiner R. (2007). The importance of lactic acid bacteria for phytate degradation during cereal dough fermentation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55: 2993-2997. [DOI: 10.1021/jf063507n] [DOI:10.1021/jf063507n] [PMID]

27. Shurtleff W., Aoyagi A. (2001). The book of tempeh. 2nd edition. Ten Speed Press, California, The United States of America. pp: 8.

28. Thiex N.J., Manson H., Anderson S., Persson J. (2002). Determination of crude protein in animal feed, forage, grain, and oilseeds by using block digestion with a copper catalyst and steam distillation into boric acid: collaborative study. Journal of AOAC International. 85: 309-317. [DOI: 10.1093/jaoac/85.2.309] [DOI:10.1093/jaoac/85.2.309] [PMID]

29. Voss R.H., Ermler U., Essen L.O., Wenzl G., Kim Y.M., Flecker P. (1996). Crystal structure of the bifunctional soybean Bowman-Birk inhibitor at 0.28-nm resolution. European Journal of Biochemistry. 242: 122-131. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1432-1033. 1996.0122r.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0122r.x] [PMID]

30. Worku A., Sahu O. (2017). Significance of fermentation process on biochemical properties of Phaseolus vulgaris (red beans). Biotechnology Reports. 16: 5-11. [DOI: 10.1016/ j.btre.2017.09.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.btre.2017.09.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

31. Yang H.W., Hsu C.K., Yang Y.F. (2014). Effect of thermal treatments on anti-nutritional factors and antioxidant capabilities in yellow soybeans and green-cotyledon small black soybeans. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 94: 1794-1801. [DOI: 10.1002/jsfa.6494] [DOI:10.1002/jsfa.6494] [PMID]

32. Yudianti N.F., Yanti R., Cahyanto M.N., Rahayu E.S., Utami T. (2020). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from legume soaking water of tempeh productions. Digital Press Life Sciences. 2: 00003. [DOI: 10.29037/digitalpress.22328] [DOI:10.29037/digitalpress.22328]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |