Volume 12, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025, 12(4): 284-292 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amanto B, Samanhudi S, Ariviani S, Prabawa S. Effect of Drying Method on Physical and Chemical Properties of Butternut Squash Flour (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poiret). J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025; 12 (4) :284-292

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1337-en.html

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1337-en.html

Lectures in Program of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agricultural, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta, Indonesia

Full-Text [PDF 778 kb]

(61 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (79 Views)

Full-Text: (7 Views)

Effect of Drying Method on Physical and Chemical Properties of Butternut Squash Flour (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poiret)

B.S. Amanto 1, S. Samanhudi 2[*]* , S. Ariviani 2, S. Prabawa 2

1. Doctoral Program of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agricultural, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta, Indonesia

2. Lectures in Program of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agricultural, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta, Indonesia

HIGHLIGHTS

(1)

(1)

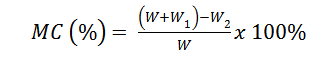

Where:

MC = material MC (%)

W = initial sample weight of material (%)

W1 = weight of cup (g)

W2 = weight of cup and material after drying

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

Where:

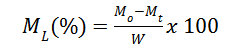

ML = loss of MC (% w/w db)

SG = added solids (% w/w)

Mo, Mt = initial sample weight, sample weight at time t (kg)

So, St = Initial solid weight, solid weight at t (kg/kg db)

Determination of beta-carotene levels

Two g of a fine sample and 2.5 ml of ethanol were added and homogenized with a vortex mixer (Gemmy-Taiwan) for one min; then another 10 ml of petroleum ether was added and homogenized for 10 min. Two ml of the solution was pipetted, then three ml of petroleum ether was added to dilute it. The radiation was carried out on a spectrophotometer (UV min specification of 1240, Shimadzu, Japan) at a wavelength of 450 nm with a petroleum ether blank. A standard solution of artificial beta-carotene was prepared by dissolving 32.2 mg of potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) in distilled water to a volume of 50 ml. The wavelength used was 450 nm with a distilled water blank. Notably, the absorbance of a 20 mg potassium dichromate solution in 100 ml of distilled water is equivalent to 5.6 μg of it in 5 ml of petroleum ether.

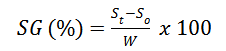

Antioxidant activity

A hundred mg of butternut squash flour was weighed and put into a test tube, then 10 ml of methanol was added and homogenized using a vortex for approximately 5 min. The test tube containing the sample was incubated for 24 h in dark conditions, and the test tube was closed using an aluminum foil.

The control solution was made from 1 ml of 0.3 mm DPPH solution dissolved in 5 ml of methanol in a reaction tube wrapped in an aluminum foil. Then, the control solution was vortexed for 1 min and incubated in dark conditions for 30 min. The sample solution incubated for 24 h was then taken as much as 0.1 ml into another test tube. Following this, 4.9 methanol and 1 ml of 0.3 mm DPPH solution were added. The sample solution was then homogenized using a vortex for 1 min and incubated in dark conditions for 30 min. The absorbance of the sample and control solutions was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 517 nm. The antioxidant activity of samples using the DPPH method is calculated using the following formula:

(4)

(4)

Color (L, a, b, and chroma)

Color measurements in butternut squash flour were carried out using a chromameter to measure color quantitatively (L, a, and b values). The Chroma parameter is also used to measure color, which is the coordinate between the values a as redness and b as yellowness. The chroma value calculated via C = √ (a2 + b2) (Silva et al., 2014).

Microstructure

analysis was performed using a Hitachi SU 3500 SEM (Japan) to observe the extent of solid penetration into the fruit and to estimate the fruit shrinkage factor during OD (Rodrigues and Fernandes, 2007). The SEM provided high-resolution images of the sample morphology, which were then analyzed using image processing technology to assess microstructural density, as described by Rahman et al. (2018).

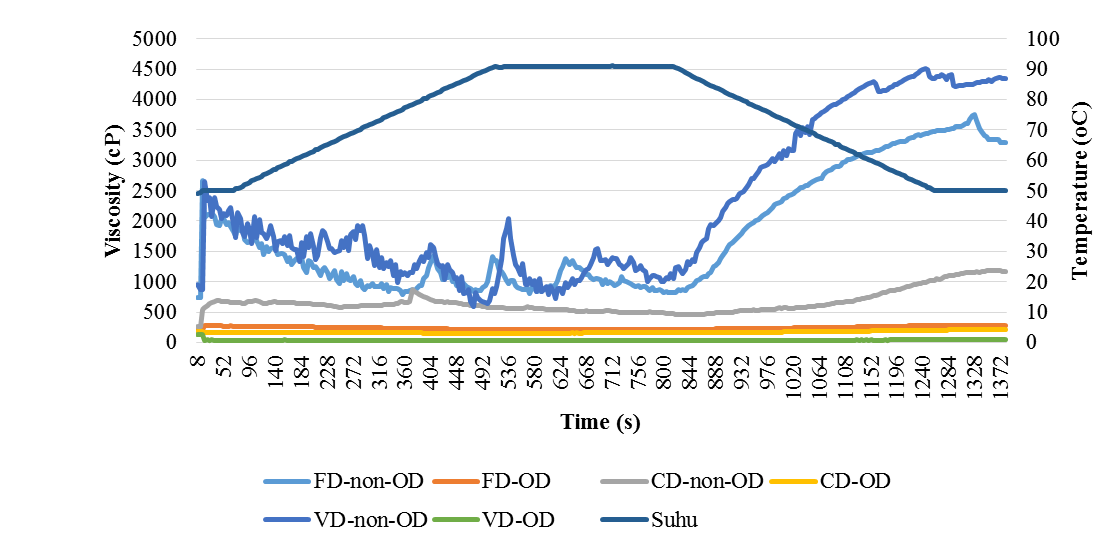

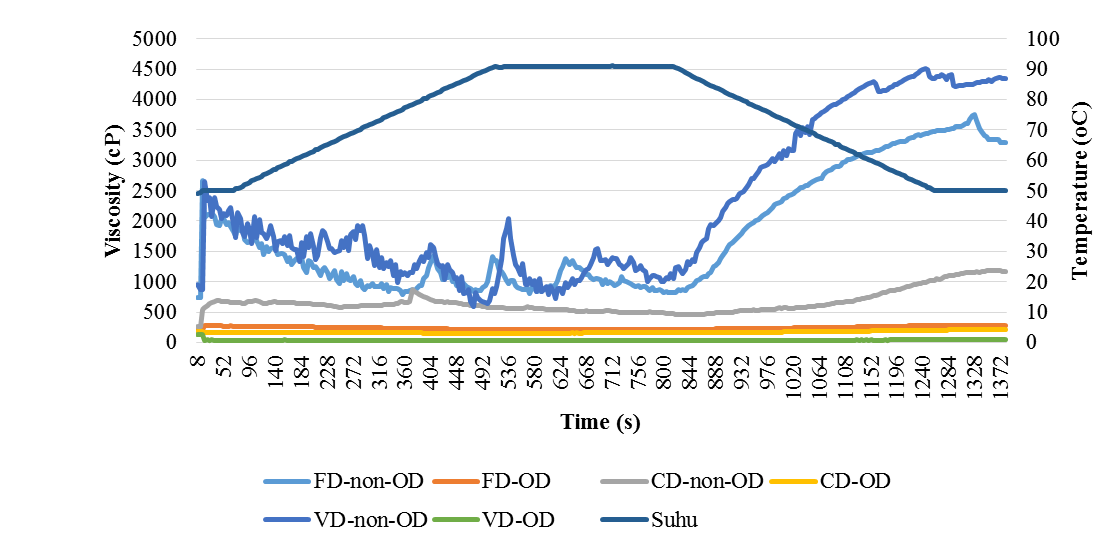

Pasting properties analysis

The amylographic properties of flour can be analyzed using a RVA, which is a viscometer equipped with a heating and cooling system to measure sample resistance under controlled stirring (Singh and Singh, 2003). A sample of dried butternut squash flour was weighed (3.5 g, db), distilled water was added, then adjusted to a total weight of 25 g. The starch sample was equilibrated at 50°C for 2 min, heated to 90 °C for 5 min at a rate of 6°C/min, maintained at 90°C for 5 min, and then cooled to 50°C for 6 min at a rate of 6°C/min. (Chinnasamy et al., 2022). Pasting Temperature (PT), Peak Viscosity (PV), peak time, Trough Viscosity (TV), Breakdown Viscosity (BV), Final Viscosity (FV), and Setback Viscosity (SBV) are determined last by the curve.

Results and discussion

Chemical characteristics of butternut squash flour

The chemical properties examined in this research were MC, beta-carotene, and antioxidant activity. MC is an important parameter and an indicator of quality in flour. Specifically for pumpkin flour, butternut squash, beta-carotene content, and antioxidant activity are important parameters because these components are the advantages of butternut squash commodities (Aydin and Gocmen, 2015). The results of the chemical characteristics of butternut squash flour with three different drying methods can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Chemical Characteristics of butternut squash flour in various drying methods

Different letter notations indicate a significant difference at α=0.05

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

Table 2: Color (L*, a*, b* and chroma) of butternut squash flour in various drying methods

Figure 2: Pasting characteristic of butternut squash flour (amylograph chart)

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

Table 3: Amylograph test results for the viscosity of butternut squash flour

B.S. Amanto 1, S. Samanhudi 2[*]*

1. Doctoral Program of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agricultural, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta, Indonesia

2. Lectures in Program of Agricultural Science, Faculty of Agricultural, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta, Indonesia

- Using the same drying method and duration, butternut squash flour that underwent osmotic dehydration exhibited lower moisture content.

- The flour prepared without osmotic dehydration retained relatively higher levels of beta-carotene and antioxidant activity.

- The samples that underwent osmotic dehydration before drying produced flour with the brightest color.

- Treatment with a salt solution during osmotic dehydration increased the heat resistance of the butternut squash flour.

| Article type Original article |

ABSTRACT Background: Butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poiret) is a type of Cucurbita moschata that is potentially a source of beta-carotene and has high antioxidant activity. The Osmotic Dehydration (OD) pretreatment has been used to retain the colour of dried butternut squash cubes. This study investigated the effects of the drying method, i.e., freeze drying, cabinet drying, And vacuum drying of butternut squash cubes with and without OD pretreatment on the flour characteristics. Methods: The study was conducted at the Faculty of Agriculture, UNS Surakarta, January 2024. Butternut squash was peeled and cut into 1×1×1 cm cubes. The OD pretreatment was carried out in 15% (w/v) salt solution. The cubes treated with or without OD were then dried, further ground into powder, and sieved to produce flour. The flour’s characteristics tested included moisture, beta-carotene, antioxidant activity, colour, and pasting properties. The data was statistically analyzed with analysis of variance, followed by the Duncan multiple range test at p<0.05 using IBM Statistics 25. Results: The drying method significantly impacted the characteristics of the butternut squash flour. The moisture, beta-carotene, and antioxidant activity of flour pretreated with OD were lower than those without OD in all drying techniques. The highest L, b, and chroma values were observed in freeze dried and OD samples, and the lowest were in the cabinet dried and non-OD samples. OD pretreatment generated a denser microstructure with fewer cavities; protein and fiber on the starch granule surface were replaced by salt, causing greater starch aggregation, resulting in flour with higher thermal stability than that from non-OD pretreatment. Conclusions: The drying methods impacted the chemical, physical, and pasting properties of butternut squash flour. Although OD pretreatment reduced the beta-carotene content and antioxidant activity of flour, the treatment improved thermal stability, making it suitable for a wide range of food applications. © 2025, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |

|

| Keywords Food Flour Dehydration Antioxidant |

||

| Article history Received: 18 Feb 2025 Revised: 25 Oct 2025 Accepted: 25 Nov 2025 |

||

| Abbreviations BV=Breakdown Viscosity CD=Cabinet Drying DPPH=2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl FD=Freeze Drying FV=Final Viscosity MC=Moisture Content OD=Osmotic Dehydration PT= Pasting Temperature PV=Peak Viscosity RVA=Rapid Visco Analyzer SEM=Scanning Electron Microscope TV=Trough Viscosity VD=Vacuum Drying |

To cite: Amanto B. S., Samanhudi S., Ariviani S., Prabawa S. (2025). Effect of drying method on physical and chemical properties of butternut squash flour (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poiret). Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control. 12: 284-292.

Introduction

Introduction

Cucurbita moschata is a vegetable with a significant source of beta-carotene levels. Most vegetables have a high Moisture Content (MC) and are easily damaged (Chong and Law, 2011). Therefore, a processing method is required to extend their shelf life. Flouring process is one of these methods. Flour-based products offer distinct advantages, including high functionality, enhanced shelf-stability, and logistical efficiencies in distribution. There are many types of pumpkins; butternut squash, is a type of pumpkin with relatively high economic value. The fiber content of butternut squash is around 2.20–2.97%, protein at 0.76–1.45%, sugar at 2.15–2.90%, fat at 0.12–0.17%, carbohydrates at 6.47–8.18%, and carotenoids at 34.54–39.53 µg/g (Armesto et al., 2020). Therefore, it is an excellent complementary food for breastfed babies.

The flouring process involves several stages that most determine its quality, namely the drying process; therefore an appropriate drying method is essential. The quality of the drying results is influenced by several factors, one of which is the drying method (Kudra and Mujumdar, 2009). Several drying methods include sunlight, Cabinet Drying (CD), Freeze Drying (FD), Vacuum Drying (VD), microwave drying, and spray drying (Chong and Law, 2011). Pretreatment of the dried material can also influence the drying results (Yadav and Singh, 2014). Preliminary treatment of materials includes size reduction, blanching, and Osmotic Dehydration (OD). The treatment of the air media used, such as vacuum, temperature, humidity reduction, modulation addition, and others, also plays a crucial role. (Kudra and Mujumdar, 2009). OD is a preliminary treatment which is carried out by soaking the material in a high concentration solution (for example salt, sugar, or something else). OD in pumpkin affects the chemical composition and structure of the material, which can reduce the MC of the material before the drying process (Ciurzyńska et al., 2013). The pretreatment of OD on butternut squash can also prevent color damage (Ramya and Jain, 2017), improve the quality of food products (Aras et al., 2019), minimize stress due to heat, and reduce energy input (Almena et al., 2019). OD, conducted with progressively higher salt concentrations, led to a reduction in flour moisture and beta-carotene content, while concurrently increasing its protein, fat, ash, fiber, and carbohydrate content (Dwivedi et al., 2023).

For materials containing thermally labile components, temperature is a critical parameter in the selection of an appropriate drying method. Drying methods yield varying quality outcomes (Beaudry et al., 2004). This study aimed to determine the effect of drying methods (CD, VD, and FD) on the main parameters of butternut squash flour, namely color, MC, beta carotene content, and antioxidant activity. Additionally, it is essential to evaluate the properties of the resulting flour paste.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Butternut squash was attained from the Karanganyar region, Central Java; distilled water and table salt (NaCl) were purchased from a local chemical shop. Other ingredients included methanol (Supelco, German), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) reagent (Sigma Aldrich, German), petroleum ether (Smartlab, German), ethanol (Supelco, German), and K2Cr2O7 (MERCK, German). Sampling ensured that pumpkins were ripe and ready to be harvested, that they had normal growth, were not deformed, and had orange skin and flesh. The harvest age was guaranteed to be around three months, weighing 1–2 kg.

Equipment and instrumentation

A set of tools were used for OD treatment including a stirrer (Heidolph, Germany), a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV min specification of 1240, Shimadzu, Japan), used for analysis of beta-carotene and antioxidant activity; and chromameter (Minolta, Japan) to measure color quantitatively (L, a, and b values), Cabinet dryer (Local, Indonesian), vacuum dryer (BK-FD10P-BIOBASE, BIOBASE, China) dan freeze dryer (BK-FD10P-BIOBASE, China); with vacuum pressure ≤10 Pa, no-load temperature <-50 oC), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Hitachi SU 3500, Japan) and Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA, RVA AACC76 22 61, China).

Preparation of research materials

The research was conducted at the Faculty of Agriculture, Sebelas Maret University in January 2024. Butternut squash that were met with the requirements were selected, cleaned, peeled, seeded, and cut into 1×1×1 cm cubes. Specifically for the initial OD treatment, the process was carried out with a ratio of ingredients and salt solution of 1:5 (w/v) (Manzoor et al., 2017) at room temperature (25 oC). Based on previous research, the optimal conditions included a salt solution concentration of 15% w/v, a stirring speed of 25 rpm and a soaking time of 155 min (Amanto et al, 2024). After completing OD, the pumpkin pieces were rinsed with clean water to remove excess salt and were dried using absorbent tissues. The drying process was carried out using three methods, namely, CD, VD, and FD. CD was conducted at 60 °C for 18 h. Samples, either pretreated with OD or untreated, were placed in the drying cabinet and removed after 18 h. Then, they were cooled to room temperature and milled to a size of 60-80 mesh. The exact process was applied to FD and VD methods. FD was carried out at a temperature of -20 °C with a pressure below 600 Pa for 20-24 h. VD was conducted at approximately 20-25 °C for 30-36 h, with a pressure below 600 Pa. The treatments used in this study were FD and non-OD (FD-non-OD) and with OD (FD-OD), CD and non-OD (CD-non-OD) and with OD (CD-OD), and VD and non-OD (VD-non-OD) and with OD (VD-OD).

The flouring process involves several stages that most determine its quality, namely the drying process; therefore an appropriate drying method is essential. The quality of the drying results is influenced by several factors, one of which is the drying method (Kudra and Mujumdar, 2009). Several drying methods include sunlight, Cabinet Drying (CD), Freeze Drying (FD), Vacuum Drying (VD), microwave drying, and spray drying (Chong and Law, 2011). Pretreatment of the dried material can also influence the drying results (Yadav and Singh, 2014). Preliminary treatment of materials includes size reduction, blanching, and Osmotic Dehydration (OD). The treatment of the air media used, such as vacuum, temperature, humidity reduction, modulation addition, and others, also plays a crucial role. (Kudra and Mujumdar, 2009). OD is a preliminary treatment which is carried out by soaking the material in a high concentration solution (for example salt, sugar, or something else). OD in pumpkin affects the chemical composition and structure of the material, which can reduce the MC of the material before the drying process (Ciurzyńska et al., 2013). The pretreatment of OD on butternut squash can also prevent color damage (Ramya and Jain, 2017), improve the quality of food products (Aras et al., 2019), minimize stress due to heat, and reduce energy input (Almena et al., 2019). OD, conducted with progressively higher salt concentrations, led to a reduction in flour moisture and beta-carotene content, while concurrently increasing its protein, fat, ash, fiber, and carbohydrate content (Dwivedi et al., 2023).

For materials containing thermally labile components, temperature is a critical parameter in the selection of an appropriate drying method. Drying methods yield varying quality outcomes (Beaudry et al., 2004). This study aimed to determine the effect of drying methods (CD, VD, and FD) on the main parameters of butternut squash flour, namely color, MC, beta carotene content, and antioxidant activity. Additionally, it is essential to evaluate the properties of the resulting flour paste.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Butternut squash was attained from the Karanganyar region, Central Java; distilled water and table salt (NaCl) were purchased from a local chemical shop. Other ingredients included methanol (Supelco, German), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) reagent (Sigma Aldrich, German), petroleum ether (Smartlab, German), ethanol (Supelco, German), and K2Cr2O7 (MERCK, German). Sampling ensured that pumpkins were ripe and ready to be harvested, that they had normal growth, were not deformed, and had orange skin and flesh. The harvest age was guaranteed to be around three months, weighing 1–2 kg.

Equipment and instrumentation

A set of tools were used for OD treatment including a stirrer (Heidolph, Germany), a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV min specification of 1240, Shimadzu, Japan), used for analysis of beta-carotene and antioxidant activity; and chromameter (Minolta, Japan) to measure color quantitatively (L, a, and b values), Cabinet dryer (Local, Indonesian), vacuum dryer (BK-FD10P-BIOBASE, BIOBASE, China) dan freeze dryer (BK-FD10P-BIOBASE, China); with vacuum pressure ≤10 Pa, no-load temperature <-50 oC), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Hitachi SU 3500, Japan) and Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA, RVA AACC76 22 61, China).

Preparation of research materials

The research was conducted at the Faculty of Agriculture, Sebelas Maret University in January 2024. Butternut squash that were met with the requirements were selected, cleaned, peeled, seeded, and cut into 1×1×1 cm cubes. Specifically for the initial OD treatment, the process was carried out with a ratio of ingredients and salt solution of 1:5 (w/v) (Manzoor et al., 2017) at room temperature (25 oC). Based on previous research, the optimal conditions included a salt solution concentration of 15% w/v, a stirring speed of 25 rpm and a soaking time of 155 min (Amanto et al, 2024). After completing OD, the pumpkin pieces were rinsed with clean water to remove excess salt and were dried using absorbent tissues. The drying process was carried out using three methods, namely, CD, VD, and FD. CD was conducted at 60 °C for 18 h. Samples, either pretreated with OD or untreated, were placed in the drying cabinet and removed after 18 h. Then, they were cooled to room temperature and milled to a size of 60-80 mesh. The exact process was applied to FD and VD methods. FD was carried out at a temperature of -20 °C with a pressure below 600 Pa for 20-24 h. VD was conducted at approximately 20-25 °C for 30-36 h, with a pressure below 600 Pa. The treatments used in this study were FD and non-OD (FD-non-OD) and with OD (FD-OD), CD and non-OD (CD-non-OD) and with OD (CD-OD), and VD and non-OD (VD-non-OD) and with OD (VD-OD).

Experimental design

The experimental design used in this research was a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with drying and OD treatment methods, namely FD, CD, and VD, each drying using materials treated with and without OD. The research was carried out using triplicate samples and two replicate analyses. The research data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with IBM SPSS version 25 software. When significant differences were found between treatments, Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was performed at a significance level of α=0.05.

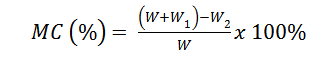

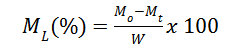

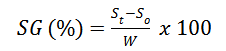

Determination of MC

The gravimetric method used for fruit and vegetables for determining water content in flour products is calculated in equation 1 (Manzoor et al., 2017). Calculation of moisture loss content and addition of solids (solid gain) are via equations 2 and 3.

The experimental design used in this research was a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with drying and OD treatment methods, namely FD, CD, and VD, each drying using materials treated with and without OD. The research was carried out using triplicate samples and two replicate analyses. The research data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA with IBM SPSS version 25 software. When significant differences were found between treatments, Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was performed at a significance level of α=0.05.

Determination of MC

The gravimetric method used for fruit and vegetables for determining water content in flour products is calculated in equation 1 (Manzoor et al., 2017). Calculation of moisture loss content and addition of solids (solid gain) are via equations 2 and 3.

(1)

(1)Where:

MC = material MC (%)

W = initial sample weight of material (%)

W1 = weight of cup (g)

W2 = weight of cup and material after drying

(2)

(2) (3)

(3) Where:

ML = loss of MC (% w/w db)

SG = added solids (% w/w)

Mo, Mt = initial sample weight, sample weight at time t (kg)

So, St = Initial solid weight, solid weight at t (kg/kg db)

Determination of beta-carotene levels

Two g of a fine sample and 2.5 ml of ethanol were added and homogenized with a vortex mixer (Gemmy-Taiwan) for one min; then another 10 ml of petroleum ether was added and homogenized for 10 min. Two ml of the solution was pipetted, then three ml of petroleum ether was added to dilute it. The radiation was carried out on a spectrophotometer (UV min specification of 1240, Shimadzu, Japan) at a wavelength of 450 nm with a petroleum ether blank. A standard solution of artificial beta-carotene was prepared by dissolving 32.2 mg of potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) in distilled water to a volume of 50 ml. The wavelength used was 450 nm with a distilled water blank. Notably, the absorbance of a 20 mg potassium dichromate solution in 100 ml of distilled water is equivalent to 5.6 μg of it in 5 ml of petroleum ether.

Antioxidant activity

A hundred mg of butternut squash flour was weighed and put into a test tube, then 10 ml of methanol was added and homogenized using a vortex for approximately 5 min. The test tube containing the sample was incubated for 24 h in dark conditions, and the test tube was closed using an aluminum foil.

The control solution was made from 1 ml of 0.3 mm DPPH solution dissolved in 5 ml of methanol in a reaction tube wrapped in an aluminum foil. Then, the control solution was vortexed for 1 min and incubated in dark conditions for 30 min. The sample solution incubated for 24 h was then taken as much as 0.1 ml into another test tube. Following this, 4.9 methanol and 1 ml of 0.3 mm DPPH solution were added. The sample solution was then homogenized using a vortex for 1 min and incubated in dark conditions for 30 min. The absorbance of the sample and control solutions was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 517 nm. The antioxidant activity of samples using the DPPH method is calculated using the following formula:

(4)

(4)Color (L, a, b, and chroma)

Color measurements in butternut squash flour were carried out using a chromameter to measure color quantitatively (L, a, and b values). The Chroma parameter is also used to measure color, which is the coordinate between the values a as redness and b as yellowness. The chroma value calculated via C = √ (a2 + b2) (Silva et al., 2014).

Microstructure

analysis was performed using a Hitachi SU 3500 SEM (Japan) to observe the extent of solid penetration into the fruit and to estimate the fruit shrinkage factor during OD (Rodrigues and Fernandes, 2007). The SEM provided high-resolution images of the sample morphology, which were then analyzed using image processing technology to assess microstructural density, as described by Rahman et al. (2018).

Pasting properties analysis

The amylographic properties of flour can be analyzed using a RVA, which is a viscometer equipped with a heating and cooling system to measure sample resistance under controlled stirring (Singh and Singh, 2003). A sample of dried butternut squash flour was weighed (3.5 g, db), distilled water was added, then adjusted to a total weight of 25 g. The starch sample was equilibrated at 50°C for 2 min, heated to 90 °C for 5 min at a rate of 6°C/min, maintained at 90°C for 5 min, and then cooled to 50°C for 6 min at a rate of 6°C/min. (Chinnasamy et al., 2022). Pasting Temperature (PT), Peak Viscosity (PV), peak time, Trough Viscosity (TV), Breakdown Viscosity (BV), Final Viscosity (FV), and Setback Viscosity (SBV) are determined last by the curve.

Results and discussion

Chemical characteristics of butternut squash flour

The chemical properties examined in this research were MC, beta-carotene, and antioxidant activity. MC is an important parameter and an indicator of quality in flour. Specifically for pumpkin flour, butternut squash, beta-carotene content, and antioxidant activity are important parameters because these components are the advantages of butternut squash commodities (Aydin and Gocmen, 2015). The results of the chemical characteristics of butternut squash flour with three different drying methods can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Chemical Characteristics of butternut squash flour in various drying methods

| Treatment | Moisture content (% wb) | Beta-carotene (µg/g wb) | Antioxidant Activity (% inhibition/g wb) |

| FD-non-OD | 12.57±0.02 e | 24.48±0.07 d | 4953.94±39.57 f |

| FD-OD | 10.45±0.06 b | 21.54±0.73 c | 3113.81±24.35 d |

| CD-non-OD | 12.34±0.01 d | 23.49±0.04 d | 1089.70±55.52 b |

| CD-OD | 9.34±0.12 a | 11.94±0.19 a | 332.21±23.98 a |

| VD-non-OD | 12.73±0.02 f | 23.89±0.21 d | 4467.55±27.39 e |

| VD-OD | 11.29±0.01c | 20.44±0.55 b | 2864.15±30.44 c |

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

Based on Table 1, it the MC of butternut squash flour ranged from 9.34%-12.72% wb. The final MC was measured after the same drying time for each method; the MC of flour treated with OD was lower than that without OD. This is because OD pretreatment reduces the initial moisture of the material compared to non-OD treatments (Paradkar and Sahu, 2018). Within this range, the MC of flour was met with the requirements of Indonesian National Standard (INS) 3751:2009 (14.5% maximum), as the MC of pumpkin flour ranged between 11.47%-13.26%. Consequently, if the target MC is the same for all methods, the drying time for OD-treated materials can be shorter. Table 1 shows that the beta-carotene in OD treated samples was lower than in non-OD samples for each drying method. This is likely because salt can reduce beta-carotene levels and antioxidant activity. The highest level of beta-carotene was found in the FD samples without any OD pretreatment (24.48±0.07 µg/g wb). Similar to the study conducted in 2023 which reported that soaking in a salt solution can decrease beta-carotene levels (Dwivedi et al, 2023). For instance, a 15% salt solution with a 30 min soak can reduce beta-carotene levels from 2.35±0.005 mg/100 g to 2.08±0.002 mg/100 g. The antioxidant activity was higher in samples treated with OD with the highest antioxidant activity obtained by FD. However, beta-carotene levels and the antioxidant activity were lower in samples treated with OD, consistent with findings that sodium chloride can reduce antioxidant activity (Zhang et al, 2021; Zhang et al., 2023).

Color

Color is represented by a 3-dimensional color scale, namely L*, a*, b*, and chroma. The table below shows the color of butternut squash flour with various drying methods and pretreatment.

Color

Color is represented by a 3-dimensional color scale, namely L*, a*, b*, and chroma. The table below shows the color of butternut squash flour with various drying methods and pretreatment.

Table 2: Color (L*, a*, b* and chroma) of butternut squash flour in various drying methods

| Treatment | L* | a* | b* | Chroma |

| FD-non-OD | 74.53±0.26 b | 4.48±0.67 d | 53.05±0.59 d | 53.24±0.62 d |

| FD-OD | 79.61±0.33 e | 3.62±0.27 c | 54.52±0.15 e | 54.64±0.15 e |

| CD-non-OD | 69.93±0.02 a | 6.33±0.26 f | 40.48±0.33 a | 40.98±0.27 a |

| CD-OD | 78.41±0.47 d | 1.51±0.04 a | 48.50±0.09 b | 48.28±0.29 b |

| VD-non-OD | 75.38±0.57 c | 5.80±0.10 e | 51.26±0.22 c | 51.59±0.18 c |

| VD-OD | 79.56±0.05 e | 2.45±0.24 b | 53.61±0.35 d | 53.67±0.30 d |

Different letter notations indicate a significant difference at α=0.05

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

.PNG) FD-non-OD |

.PNG) CD-non-OD CD-non-OD |

.PNG) PVD-non-OD PVD-non-OD |

.PNG) FD-OD FD-OD |

.PNG) CD-OD CD-OD |

.PNG) VD-OD VD-OD |

Figure 1: Color of butternut squash flour with different drying methods and preliminary treatments

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

The results depicted in Table 2 indicated that the color of the flour is relatively bright (average L* value above 70) and tends to be yellow (b* positive). The FD method obtained a relatively brightand yellowish color (Chroma value +54) because FD is able to reduce the degradation of color and other functional compounds (Roongruangsri and Bronlund, 2015). The OD treatment was also able to provide a brighter color compared to the NON-OD treatment. Figure 1 shows the appearance of the color of the butternut squash flour obtained.

Based on these results, the FD-OD treatment was chosen as the best treatment in making butternut squash flour. In FD-OD, the results obtained for each parameter were MC (10.45%), beta carotene (21.54 µg/g db), antioxidant activity (3113.81% inhibition/g), L* value (79.61), a* value (3.62), and b* value (54.53). Similar to the study conducted by Que et al. (2008), the brightness of pumpkin flour was brighter when dried with a freeze dryer compared to a hot air dryer. In comparison, the study conducted by Dwivedi et al. (2023) produced pumpkin flour (Cucurbita maxima) using a 30-min OD treatment in a 15% salt solution at 1:4 ingredients to solution ratioThe resulting color values were: L = 60.2±1.3, a = 1.7±2.5, and b = 32.2±2.13.

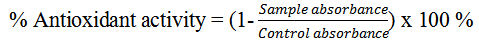

Pasting properties of the butternut squash flour

The pasting properties of flour determine its use in food products and their quality. To obtain appropriate flour characteristics, several modifications are made to the manufacturing process. Modifications can be done physically, chemically, or biologically. One such method involves the preliminary processing of the raw material prior to milling it into flour.. The purpose of a modification is to obtain flour properties suitable for further processing.

The pasting properties of flour are critical for it application in food processing, which is associated with viscosity, shelf life, retrogradation, and syneresis (Kartikasari et al., 2016).

Based on these results, the FD-OD treatment was chosen as the best treatment in making butternut squash flour. In FD-OD, the results obtained for each parameter were MC (10.45%), beta carotene (21.54 µg/g db), antioxidant activity (3113.81% inhibition/g), L* value (79.61), a* value (3.62), and b* value (54.53). Similar to the study conducted by Que et al. (2008), the brightness of pumpkin flour was brighter when dried with a freeze dryer compared to a hot air dryer. In comparison, the study conducted by Dwivedi et al. (2023) produced pumpkin flour (Cucurbita maxima) using a 30-min OD treatment in a 15% salt solution at 1:4 ingredients to solution ratioThe resulting color values were: L = 60.2±1.3, a = 1.7±2.5, and b = 32.2±2.13.

Pasting properties of the butternut squash flour

The pasting properties of flour determine its use in food products and their quality. To obtain appropriate flour characteristics, several modifications are made to the manufacturing process. Modifications can be done physically, chemically, or biologically. One such method involves the preliminary processing of the raw material prior to milling it into flour.. The purpose of a modification is to obtain flour properties suitable for further processing.

The pasting properties of flour are critical for it application in food processing, which is associated with viscosity, shelf life, retrogradation, and syneresis (Kartikasari et al., 2016).

Figure 2: Pasting characteristic of butternut squash flour (amylograph chart)

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

Figure 2 shows a graph of the pasting properties of butternut squash flour. Pasting properties, including PV, TV, BV, Setback Viscosity (SV), FV, and PT of butternut squash flour prepared with various drying methods, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Amylograph test results for the viscosity of butternut squash flour

| Sam-pel | Peak Viscosity (cP) |

Trough Viscosity (cP) |

Breakdown Viscosity (cP) |

Setback Viscosity (cP) | Final Viscosity (cP) |

Pasting Temperatur (OC) |

Peak Time (mnt) |

| FD-non-OD | 1433.00±6.50 | 814.00±3.90 | 619.00±2.01 | 2479.00±4.17 | 3293.00±2.00 | 50.55±0.01 | 6.80±0.01 |

| FD-OD | 256.00±1.09 | 212.00±0.75 | 44.00±0.00 | 71.00±0.01 | 283.00±0.45 | - | 3.07±0.00 |

| CD-non-OD | 868.00±2.07 | 459.00±0.98 | 409.00±0.20 | 716.00±0.30 | 1175.00±0.89 | 52.05±0.01 | 6.20±0.02 |

| CD-OD | 165.00±0.56 | 157.00±0.01 | 8.00±0.00 | 49.00±0.00 | 206.00±0.34 | - | 3.07±0.00 |

| VD-non-OD | 2048.00±8.30 | 1003.00±0.88 | 1045.00±2.01 | 3346.00±7.30 | 4349.00±5.37 | 50.45±0.00 | 8.93±0.02 |

| VD-OD | 38.00±0.02 | 35.00±0.01 | 3.00±0.00 | 6.00±0.00 | 41.00±0.00 | - | 3.20±0.00 |

CD=Cabinet Drying; FD=Freeze Drying; OD=Osmotic Dehydration; VD=Vacuum Drying

All parameters of the paste properties showed greater values in the treatment without OD than in those with OD. It can be concluded that OD pretreatment with a salt solution provided lower paste viscosity values (PV, TV, BV, SV, and FV). Similar to the study conducted by Kose et al. (2019), which reported that salt solution can reduce pasting characteristics. The same result was achieved by Kim et al. (2023), who examined the effect of NaCl on the properties of a mixture of corn flour and methyl cellulose paste. It was also found that NaCl can reduce pasting characteristics. The BV value showed how easily the starch was gelatinized (broke down) (Varavinit at al., 2003). In flour samples without pretreatment, the highest BV value was found in flour dried with a vacuum dryer, followed by the freeze dryer, and then the cabinet dryer. Regarding the drying temperatures, the cabinet dryer used the highest temperature (60 °C), while the vacuum and freeze dryers operated at much lower temperatures (approximately -20 °C). According to Aviara et al. (2010), high temperatures negatively impact BV by inhibiting the flour's ability to gelatinize.

A high SV value indicates that the flour undergoes rapid retrogradation after cooling. For bakery products like cakes, cookies, and bread, a high SV is undesirable as it leads to hardness upon cooling. Instead, flour with a high SV is more suitable for use as a filler agent.

The values in Table 3 show that all samples not treated with OD had a higher viscosity than those treated with OD. Among the three treatments without OD, the highest viscosity value was from the sample dried using VD, and the lowest was from CD. It is suspected that temperature differences during the drying process can affect viscosity. The salt content in the material can also affect viscosity (Muhandri, 2007). The viscosity of flours with OD treatment was decreased even upon heating. Among the drying methods, the VD produced flour with the lowest viscosity.

The initial PT is the temperature at which starch granules begin to absorb water and swell, marked by an initial increase in viscosity. For butternut squash flour treated with OD, this initial gelatinization temperature was undetectable. In contrast, untreated flour had an average initial gelatinization temperature of approximately 50 °C. Only the OD-treated flour dried with CD exhibited a slightly higher temperature of 52 °C. Moreover, the effect of NaCl was very significant on the viscosity of the flour (Muhandri, 2007).

BV, calculated as the difference between PV and TV, indicates a paste's stability under heat. The lower the BV, the more stable the pasta is against heating. (Fiqtinovri, 2020; Muhandri, 2007). Accordingly, some butternut squash flours treated with OD demonstrated considerable heat resistance.

Microstructure of butternut squash slices

Food microstructure is defined as the arrangement of cell and intercellular space in food (Aguilera, 2005). Since structural changes during food processing can reduce food quality, the main concern is to maintain the original microstructure of food ingredients (Chen and Mujumdar, 2008). A material's capacity to integrate with other materials is determined by its structure.

A high SV value indicates that the flour undergoes rapid retrogradation after cooling. For bakery products like cakes, cookies, and bread, a high SV is undesirable as it leads to hardness upon cooling. Instead, flour with a high SV is more suitable for use as a filler agent.

The values in Table 3 show that all samples not treated with OD had a higher viscosity than those treated with OD. Among the three treatments without OD, the highest viscosity value was from the sample dried using VD, and the lowest was from CD. It is suspected that temperature differences during the drying process can affect viscosity. The salt content in the material can also affect viscosity (Muhandri, 2007). The viscosity of flours with OD treatment was decreased even upon heating. Among the drying methods, the VD produced flour with the lowest viscosity.

The initial PT is the temperature at which starch granules begin to absorb water and swell, marked by an initial increase in viscosity. For butternut squash flour treated with OD, this initial gelatinization temperature was undetectable. In contrast, untreated flour had an average initial gelatinization temperature of approximately 50 °C. Only the OD-treated flour dried with CD exhibited a slightly higher temperature of 52 °C. Moreover, the effect of NaCl was very significant on the viscosity of the flour (Muhandri, 2007).

BV, calculated as the difference between PV and TV, indicates a paste's stability under heat. The lower the BV, the more stable the pasta is against heating. (Fiqtinovri, 2020; Muhandri, 2007). Accordingly, some butternut squash flours treated with OD demonstrated considerable heat resistance.

Microstructure of butternut squash slices

Food microstructure is defined as the arrangement of cell and intercellular space in food (Aguilera, 2005). Since structural changes during food processing can reduce food quality, the main concern is to maintain the original microstructure of food ingredients (Chen and Mujumdar, 2008). A material's capacity to integrate with other materials is determined by its structure.

.PNG) |

.PNG) |

|

.PNG) |

.PNG) |

Figure 3: Scanning electron microscope of butternut squash slices without (1 and 2) and with osmotic dehydration pretreatment (3 and 4). The magnification was 500× for 1 and 3, and 1000× for 2 and 4.

The difference in the shape of the microstructure before and after the OD process was that before the OD process, the fibers appeared to be elongated, and after the OD, they appeared shorter with substantial material filling the inter-fiber spaces. This condition is as shown in Figure 3. This observation is consistent with the findings of Tan et al. (2020), who reported that the microstructure which contained NaCl resulted in a more compact network structure (Tan et al., 2020). Therefore, changes in microstructure due to the addition of salt are thought to contribute to the rheological differences. The OD process reduced the initial MC of the material, which could subsequently extend the required drying time. These structural changes function to control mass transport, including the movement of water and solutes (Tortoe, 2010). A visible effect of OD was that the final MC of treated materials was consistently lower. Blanching and OD could induce changes to the macro-, micro-, and ultrastructure of tissues, and water distribution, with some modifications greatly influencing the mechanical behavior and, therefore, the perceived texture (Alzamora et al., 2008). However, due to the complex relationships and interdependence of fruit tissue material properties, including mechanical properties, it is difficult to predict and explain (Kunzek et al., 1999). Nonetheless, it is established that such treatments significantly influence compression, viscoelastic properties, and texture (Garcia Loredo et al., 2013). For instance, Monteiro et al. (2018) demonstrated that applying FD to pumpkin cubes yields a spongier microstructure compared to CD.

Conclusion

The final MC, beta-carotene content, and antioxidant activity of butternut squash flour pretreated with OD were lower than that in flour without OD treatment. Among the drying methods, the FD best preserved these qualities, followed by the VD and the CD. The highest L, b and Chroma values were found in FD-OD treated flour, while the lowest values were in CD-non-OD flour. OD treatment with a salt solution resulted in a denser microstructure with fewer voids. OD-treated flour demonstrated greater heat resistance compared to non-OD flour. Furthermore, OD pretreatment enhanced the thermal stability of butternut squash flour, suggesting its suitability for a wider range of food applications.

Author contributions

B.S.A., S.S., and S.A. designed the study; B.S.A., S.A., and S.P. conducted the experimental work; B.S.A., S.S., S.A., and S.P. analyzed the data; B.S.A. and S.P. wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; B.S.A. supervised the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Faculty of Agriculture, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) for the support.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received grant from Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta.

Ethical consideration

Not Applicable.

References

Aguilera J.M. (2005). Why food microstructure? Journal of Food Engineering. 67: 3-11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.050]

Almena A., Goode K.R., Bakalis S., Fryer P.J., Lopez-Quiroga E. (2019). Optimising food dehydration processes: energy-efficient drum-dryer operation. Energy Procedia. 161: 174–181. [DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.078]

Conclusion

The final MC, beta-carotene content, and antioxidant activity of butternut squash flour pretreated with OD were lower than that in flour without OD treatment. Among the drying methods, the FD best preserved these qualities, followed by the VD and the CD. The highest L, b and Chroma values were found in FD-OD treated flour, while the lowest values were in CD-non-OD flour. OD treatment with a salt solution resulted in a denser microstructure with fewer voids. OD-treated flour demonstrated greater heat resistance compared to non-OD flour. Furthermore, OD pretreatment enhanced the thermal stability of butternut squash flour, suggesting its suitability for a wider range of food applications.

Author contributions

B.S.A., S.S., and S.A. designed the study; B.S.A., S.A., and S.P. conducted the experimental work; B.S.A., S.S., S.A., and S.P. analyzed the data; B.S.A. and S.P. wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; B.S.A. supervised the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Faculty of Agriculture, Sebelas Maret University (UNS) for the support.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received grant from Sebelas Maret University (UNS) Surakarta.

Ethical consideration

Not Applicable.

References

Aguilera J.M. (2005). Why food microstructure? Journal of Food Engineering. 67: 3-11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.050]

Almena A., Goode K.R., Bakalis S., Fryer P.J., Lopez-Quiroga E. (2019). Optimising food dehydration processes: energy-efficient drum-dryer operation. Energy Procedia. 161: 174–181. [DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.078]

Alzamora S.M., Viollaz P.E., Martínez V.Y., Nieto A.B., Salvatori D. (2008). Exploring the linear viscoelastic properties structure relationship in processed fruit tissues. In: Gutiérrez-López, G.F., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Welti-Chanes, J., Parada-Arias, E. (Editors). Food engineering: integrated approaches. Springer, New York, NY, United States. pp: 155-181. [DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-75430-7_9]

Amanto B.S., Samanhudi S., Ariviani S., Prabawa S. (2024). Osmotic dehydration optimization of butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata Duch) using response surface methodology. Food Research. 8: 201-209. [DOI: 10.26656/fr.2017.8(S2).152]

Aras L., Supratomo S., Salengke S. (2019). Effect of temperature and concentration of sugar solution in the process of osmotic dehydration of papaya (Carica papaya L .). Jurnal AgriTechno. 12: 110–120. [DOI: 10.20956/at.v0i0.219]

Armesto J., Rocchetti,G., Senizza B., Pateiro M., Barba F.J., Domínguez R., Lucini L., Lorenzo J.M. (2020). Nutritional characterization of butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata D.): effect of variety (Ariel vs. Pluto) and farming type (conventional vs. organic). Food Research International. 132: 109052. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109052]

Aviara N.A., Igbeka J.C., Nwokocha L.M. (2010). Effect of drying temperature on physicochemical properties of cassava starch. International Agrophysics. 24: 219-225.

Aydin E., Gocmen D. (2015). The influences of drying method and metabisulfite pre-treatment on the color, functional properties and phenolic acids contents and bioaccessibility of pumpkin flour. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 60:385–392. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.08.025]

Beaudry C, Raghavan G.S.V., Ratti C., Rennie T.J. (2004). Effect of four drying methods on the quality of osmotically dehydrated cranberries. Drying Technology. 22: 521-539. [DOI: 10.1081/DRT-120029999]

Chen X.D., Mujumdar A.S. (2008). Drying technologies in food processing. 1st edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken, New Jersey, United States. pp: 137-139.

Chinnasamy G., Dekeba K., Sundramurthy V.B., Dereje B. (2022). Physicochemical properties of tef starch: morphological, thermal, thermogravimetric, and pasting properties. International Journal of Food Properties. 25: 1668-1682. [DOI: 10.1080/ 10942912.2022.2098973].

Chong C.H., Law C.L. (2011). Drying of exotic fruits. In: Jangam S.V., Law C.L., Mujumdar A.S. (Editors). Vegetables and fruits volume 2. Singapore. pp: 3-4.

Ciurzyńska A., Lenart A., Kawka P. (2013). Influence of chemical composition and structure on sorption properties of freeze-dried pumpkin. Drying Technology. 31: 655–665. [DOI: 10.1080/07373937.2012.753609]

Dwivedi S., Kumar V., Singh R., Srivastava A. (2023). Effect of Osmotic dehydration on quality of pumpkin flour. Journal of Agricultural Engineering and Food Technology. 10: 1-5.

Fiqtinovri S.M. (2020). Chemical characteristics and amilography of modified cassava flour of singkong gajah (Manihot utilissima). Jurnal Agroindustri Halal. 6: 49–56. [DOI: 10.30997/jah.v6i1.2162]

Garcia Loredo A.B., Guerrero S.N., Gomez P.L., Alzamora S.M. (2013). Relationships between rheological properties, texture and structure of apple (Granny Smith var.) affected by blanching and/or osmotic dehydration. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 6: 475–488. [DOI: 10.1007/s11947-011-0701-9]

Kartikasari S.N., Sari P., Subagio A. (2016). Characterization of chemical properties, amylograpic profiles (RVA) and granular morphology (SEM) of biologically modified cassava starch. Jurnal Agroteknologi. 10: 12–24.

Kim J., Chang Y.H., and Lee Y. (2023). Effects of NaCl on the physical properties of Cornstarch–Methyl Cellulose blend and on its gel prepared with rice flour in a model system. Foods. 12: 4390. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12244390]

Kose S., Kose Y.E., Ceylan M.M. (2019). Impact of sodium chloride and ascorbic acid on pasting and textural parameters of corn starch-water and milk systems. International Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences. 9-16.

Kudra T., Mujumdar A.S. (2009). Advanced drying technologies. 2nd edition. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, United States. pp: 11-16.

Kunzek H., Kabbert R.,Gloyna D. (1999). Aspects of material science in food processing: changes in plant cell walls of fruits and vegetables. European Food Research and Technology. 208: 233-250. [DOI: 10.1007/s002170050410]

Manzoor M., Shukla R.N., Mishra A.A., Fatima A., Nayik G.A. (2017). Osmotic dehydration characteristics of pumpkin slices using ternary osmotic solution of sucrose and sodium chloride. Journal of Food Processing and Technology. 8: 669. [DOI: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000669]

Monteiro R.L., Link J.V., Tribuzi G., Carciofi B.A.M. Laurindo J.B. (2018). Effect of multi-flash drying and microwave vacuum drying on the microstructure and texture of pumpkin slices. LWT-Foods Science Technology. 96: 612–619. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.023]

Muhandri T. (2007). The effects of particle size, solid content, NaCl and Na2CO3 on the amilographic characteristics of corn flour and corn starch. Jurnal Teknologi dan Industri Pangan. 18: 109–117.

Paradkar V., Sahu G. (2018). Studies on drying of osmotically dehydrated apple slices. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 7: 633–642. [DOI: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.711.077]

Que F., Mao L., Fang X., Wu T. (2008). Comparison of hot air-drying and freeze-drying on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) flours. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 43: 1195–1201. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01590.x]

Rahman M.M., Gu Y.T., Karim M.A. (2018). Development of realistic food microstructure considering the structural heterogeneity of cells and intercellular space. Food Structure. 15: 9–16. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2018.01.002]

Ramya V., Jain N.K. (2017). A review on osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: an integrated approach. Journal of Food Process Engineering. 40: 1–22. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpe.12440].

Rodrigues S., Fernandes F.A.N. (2007). Image analysis of osmotically dehydrated fruits: melons dehydration in a ternary system. European Food Research and Technology. 225: 685–691. [DOI: 10.1007/s00217-006-0466-y]

Roongruangsri W., Bronlund J.E. (2015). A review of drying processes in the production of pumpkin powder. International Journal of Food Engineering. 11: 789–799. [DOI: 10.1515/ijfe-2015-0168]

Silva K.S., Fernandes M.A., Mauro M.A. (2014). Effect of calcium on the osmotic dehydration kinetics and quality of pineapple. Journal of Food Engineering. 134: 37–44. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.02.020]

Singh J., Singh N. (2003). Studies on the morphological and rheological properties of granular cold water soluble corn and potato starches. Food Hydrocolloids. 17: 63–72. [DOI: 10.1016/S0268-005X(02)00036-X]

Tan H.L., Tan T.C., Easa A.M. (2020). Effects of sodium chloride or salt substitutes on rheological properties and water-holding capacity of flour and hardness of noodles. Food Structure. 26: 100154. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2020.100154]

Tortoe C. (2010). A review of osmodehydration for food industry. African Journal of Food Science. 4: 303–324.

Varavinit S., Shobsngob S., Varanyanond W., Chinachoti P., Naivikul O. (2003). Effect of amylose content on gelatinization, retrogradation and pasting properties of flours from different cultivars of thai rice. Starch. 55: 410–415. [DOI: 10.1002/star.200300185]

Yadav A.K., Singh S.V. (2014). Osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 51: 1654-1673. [DOI: 10.1007/s13197-012-0659-2]

Zhang M., Ma J., Li J., Bian H.,Yan Z., Wang D., Xu W., Zhao Y., Shu L. (2023). Influence of NaCl on lipid oxidation and endogenous pro-oxidants/antioxidants in chicken meat. Food Science of Animal Products. 1: 9240010. [DOI: 10.26599/FSAP.2023.9240010].

Zhang Z., Lyu J., Lou H., Tang C., Zheng H., Chen S., Yu M., Hu W., Jin L., Wang C., Lv H., Lu H. (2021). Effects of elevated sodium chloride on shelf-life and antioxidant ability of grape juice sports drink. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 45: e15049. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.15049]

Armesto J., Rocchetti,G., Senizza B., Pateiro M., Barba F.J., Domínguez R., Lucini L., Lorenzo J.M. (2020). Nutritional characterization of butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata D.): effect of variety (Ariel vs. Pluto) and farming type (conventional vs. organic). Food Research International. 132: 109052. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109052]

Aviara N.A., Igbeka J.C., Nwokocha L.M. (2010). Effect of drying temperature on physicochemical properties of cassava starch. International Agrophysics. 24: 219-225.

Aydin E., Gocmen D. (2015). The influences of drying method and metabisulfite pre-treatment on the color, functional properties and phenolic acids contents and bioaccessibility of pumpkin flour. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 60:385–392. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.08.025]

Beaudry C, Raghavan G.S.V., Ratti C., Rennie T.J. (2004). Effect of four drying methods on the quality of osmotically dehydrated cranberries. Drying Technology. 22: 521-539. [DOI: 10.1081/DRT-120029999]

Chen X.D., Mujumdar A.S. (2008). Drying technologies in food processing. 1st edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken, New Jersey, United States. pp: 137-139.

Chinnasamy G., Dekeba K., Sundramurthy V.B., Dereje B. (2022). Physicochemical properties of tef starch: morphological, thermal, thermogravimetric, and pasting properties. International Journal of Food Properties. 25: 1668-1682. [DOI: 10.1080/ 10942912.2022.2098973].

Chong C.H., Law C.L. (2011). Drying of exotic fruits. In: Jangam S.V., Law C.L., Mujumdar A.S. (Editors). Vegetables and fruits volume 2. Singapore. pp: 3-4.

Ciurzyńska A., Lenart A., Kawka P. (2013). Influence of chemical composition and structure on sorption properties of freeze-dried pumpkin. Drying Technology. 31: 655–665. [DOI: 10.1080/07373937.2012.753609]

Dwivedi S., Kumar V., Singh R., Srivastava A. (2023). Effect of Osmotic dehydration on quality of pumpkin flour. Journal of Agricultural Engineering and Food Technology. 10: 1-5.

Fiqtinovri S.M. (2020). Chemical characteristics and amilography of modified cassava flour of singkong gajah (Manihot utilissima). Jurnal Agroindustri Halal. 6: 49–56. [DOI: 10.30997/jah.v6i1.2162]

Garcia Loredo A.B., Guerrero S.N., Gomez P.L., Alzamora S.M. (2013). Relationships between rheological properties, texture and structure of apple (Granny Smith var.) affected by blanching and/or osmotic dehydration. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 6: 475–488. [DOI: 10.1007/s11947-011-0701-9]

Kartikasari S.N., Sari P., Subagio A. (2016). Characterization of chemical properties, amylograpic profiles (RVA) and granular morphology (SEM) of biologically modified cassava starch. Jurnal Agroteknologi. 10: 12–24.

Kim J., Chang Y.H., and Lee Y. (2023). Effects of NaCl on the physical properties of Cornstarch–Methyl Cellulose blend and on its gel prepared with rice flour in a model system. Foods. 12: 4390. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12244390]

Kose S., Kose Y.E., Ceylan M.M. (2019). Impact of sodium chloride and ascorbic acid on pasting and textural parameters of corn starch-water and milk systems. International Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences. 9-16.

Kudra T., Mujumdar A.S. (2009). Advanced drying technologies. 2nd edition. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, United States. pp: 11-16.

Kunzek H., Kabbert R.,Gloyna D. (1999). Aspects of material science in food processing: changes in plant cell walls of fruits and vegetables. European Food Research and Technology. 208: 233-250. [DOI: 10.1007/s002170050410]

Manzoor M., Shukla R.N., Mishra A.A., Fatima A., Nayik G.A. (2017). Osmotic dehydration characteristics of pumpkin slices using ternary osmotic solution of sucrose and sodium chloride. Journal of Food Processing and Technology. 8: 669. [DOI: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000669]

Monteiro R.L., Link J.V., Tribuzi G., Carciofi B.A.M. Laurindo J.B. (2018). Effect of multi-flash drying and microwave vacuum drying on the microstructure and texture of pumpkin slices. LWT-Foods Science Technology. 96: 612–619. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.023]

Muhandri T. (2007). The effects of particle size, solid content, NaCl and Na2CO3 on the amilographic characteristics of corn flour and corn starch. Jurnal Teknologi dan Industri Pangan. 18: 109–117.

Paradkar V., Sahu G. (2018). Studies on drying of osmotically dehydrated apple slices. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 7: 633–642. [DOI: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.711.077]

Que F., Mao L., Fang X., Wu T. (2008). Comparison of hot air-drying and freeze-drying on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) flours. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 43: 1195–1201. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01590.x]

Rahman M.M., Gu Y.T., Karim M.A. (2018). Development of realistic food microstructure considering the structural heterogeneity of cells and intercellular space. Food Structure. 15: 9–16. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2018.01.002]

Ramya V., Jain N.K. (2017). A review on osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: an integrated approach. Journal of Food Process Engineering. 40: 1–22. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpe.12440].

Rodrigues S., Fernandes F.A.N. (2007). Image analysis of osmotically dehydrated fruits: melons dehydration in a ternary system. European Food Research and Technology. 225: 685–691. [DOI: 10.1007/s00217-006-0466-y]

Roongruangsri W., Bronlund J.E. (2015). A review of drying processes in the production of pumpkin powder. International Journal of Food Engineering. 11: 789–799. [DOI: 10.1515/ijfe-2015-0168]

Silva K.S., Fernandes M.A., Mauro M.A. (2014). Effect of calcium on the osmotic dehydration kinetics and quality of pineapple. Journal of Food Engineering. 134: 37–44. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.02.020]

Singh J., Singh N. (2003). Studies on the morphological and rheological properties of granular cold water soluble corn and potato starches. Food Hydrocolloids. 17: 63–72. [DOI: 10.1016/S0268-005X(02)00036-X]

Tan H.L., Tan T.C., Easa A.M. (2020). Effects of sodium chloride or salt substitutes on rheological properties and water-holding capacity of flour and hardness of noodles. Food Structure. 26: 100154. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2020.100154]

Tortoe C. (2010). A review of osmodehydration for food industry. African Journal of Food Science. 4: 303–324.

Varavinit S., Shobsngob S., Varanyanond W., Chinachoti P., Naivikul O. (2003). Effect of amylose content on gelatinization, retrogradation and pasting properties of flours from different cultivars of thai rice. Starch. 55: 410–415. [DOI: 10.1002/star.200300185]

Yadav A.K., Singh S.V. (2014). Osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 51: 1654-1673. [DOI: 10.1007/s13197-012-0659-2]

Zhang M., Ma J., Li J., Bian H.,Yan Z., Wang D., Xu W., Zhao Y., Shu L. (2023). Influence of NaCl on lipid oxidation and endogenous pro-oxidants/antioxidants in chicken meat. Food Science of Animal Products. 1: 9240010. [DOI: 10.26599/FSAP.2023.9240010].

Zhang Z., Lyu J., Lou H., Tang C., Zheng H., Chen S., Yu M., Hu W., Jin L., Wang C., Lv H., Lu H. (2021). Effects of elevated sodium chloride on shelf-life and antioxidant ability of grape juice sports drink. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 45: e15049. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.15049]

[*] Corresponding author (S. Samanhudi)

Email: samanhudi@staff.uns.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-8471

Email: samanhudi@staff.uns.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-8471

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Special

Received: 25/02/18 | Accepted: 25/11/25 | Published: 25/12/21

Received: 25/02/18 | Accepted: 25/11/25 | Published: 25/12/21

References

1. Aguilera J.M. (2005). Why food microstructure? Journal of Food Engineering. 67: 3-11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.050] [DOI:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.05.050]

2. Almena A., Goode K.R., Bakalis S., Fryer P.J., Lopez-Quiroga E. (2019). Optimising food dehydration processes: energy-efficient drum-dryer operation. Energy Procedia. 161: 174-181. [DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.078] [DOI:10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.078]

3. Alzamora S.M., Viollaz P.E., Martínez V.Y., Nieto A.B., Salvatori D. (2008). Exploring the linear viscoelastic properties structure relationship in processed fruit tissues. In: Gutiérrez-López, G.F., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Welti-Chanes, J., Parada-Arias, E. (Editors). Food engineering: integrated approaches. Springer, New York, NY, United States. pp: 155-181. [DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-75430-7_9] [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-75430-7_9]

4. Amanto B.S., Samanhudi S., Ariviani S., Prabawa S. (2024). Osmotic dehydration optimization of butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata Duch) using response surface methodology. Food Research. 8: 201-209. [DOI: 10.26656/fr.2017.8(S2).152] [DOI:10.26656/fr.2017.8(S2).152]

5. Aras L., Supratomo S., Salengke S. (2019). Effect of temperature and concentration of sugar solution in the process of osmotic dehydration of papaya (Carica papaya L .). Jurnal AgriTechno. 12: 110-120. [DOI: 10.20956/at.v0i0.219] [DOI:10.20956/at.v0i0.219]

6. Armesto J., Rocchetti,G., Senizza B., Pateiro M., Barba F.J., Domínguez R., Lucini L., Lorenzo J.M. (2020). Nutritional characterization of butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata D.): effect of variety (Ariel vs. Pluto) and farming type (conventional vs. organic). Food Research International. 132: 109052. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109052] [DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109052] [PMID]

7. Aviara N.A., Igbeka J.C., Nwokocha L.M. (2010). Effect of drying temperature on physicochemical properties of cassava starch. International Agrophysics. 24: 219-225.

8. Aydin E., Gocmen D. (2015). The influences of drying method and metabisulfite pre-treatment on the color, functional properties and phenolic acids contents and bioaccessibility of pumpkin flour. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 60:385-392. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.08.025] [DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2014.08.025]

9. Beaudry C, Raghavan G.S.V., Ratti C., Rennie T.J. (2004). Effect of four drying methods on the quality of osmotically dehydrated cranberries. Drying Technology. 22: 521-539. [DOI: 10.1081/DRT-120029999] [DOI:10.1081/DRT-120029999]

10. Chen X.D., Mujumdar A.S. (2008). Drying technologies in food processing. 1st edition. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken, New Jersey, United States. pp: 137-139.

11. Chinnasamy G., Dekeba K., Sundramurthy V.B., Dereje B. (2022). Physicochemical properties of tef starch: morphological, thermal, thermogravimetric, and pasting properties. International Journal of Food Properties. 25: 1668-1682. [DOI: 10.1080/ 10942912.2022.2098973]. [DOI:10.1080/10942912.2022.2098973]

12. Chong C.H., Law C.L. (2011). Drying of exotic fruits. In: Jangam S.V., Law C.L., Mujumdar A.S. (Editors). Vegetables and fruits volume 2. Singapore. pp: 3-4.

13. Ciurzyńska A., Lenart A., Kawka P. (2013). Influence of chemical composition and structure on sorption properties of freeze-dried pumpkin. Drying Technology. 31: 655-665. [DOI: 10.1080/07373937.2012.753609] [DOI:10.1080/07373937.2012.753609]

14. Dwivedi S., Kumar V., Singh R., Srivastava A. (2023). Effect of Osmotic dehydration on quality of pumpkin flour. Journal of Agricultural Engineering and Food Technology. 10: 1-5.

15. Fiqtinovri S.M. (2020). Chemical characteristics and amilography of modified cassava flour of singkong gajah (Manihot utilissima). Jurnal Agroindustri Halal. 6: 49-56. [DOI: 10.30997/jah.v6i1.2162] [DOI:10.30997/jah.v6i1.2162]

16. Garcia Loredo A.B., Guerrero S.N., Gomez P.L., Alzamora S.M. (2013). Relationships between rheological properties, texture and structure of apple (Granny Smith var.) affected by blanching and/or osmotic dehydration. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 6: 475-488. [DOI: 10.1007/s11947-011-0701-9] [DOI:10.1007/s11947-011-0701-9]

17. Kartikasari S.N., Sari P., Subagio A. (2016). Characterization of chemical properties, amylograpic profiles (RVA) and granular morphology (SEM) of biologically modified cassava starch. Jurnal Agroteknologi. 10: 12-24.

18. Kim J., Chang Y.H., and Lee Y. (2023). Effects of NaCl on the physical properties of Cornstarch-Methyl Cellulose blend and on its gel prepared with rice flour in a model system. Foods. 12: 4390. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12244390] [DOI:10.3390/foods12244390] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Kose S., Kose Y.E., Ceylan M.M. (2019). Impact of sodium chloride and ascorbic acid on pasting and textural parameters of corn starch-water and milk systems. International Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences. 9-16.

20. Kudra T., Mujumdar A.S. (2009). Advanced drying technologies. 2nd edition. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, United States. pp: 11-16. [DOI:10.1201/9781420073898]

21. Kunzek H., Kabbert R.,Gloyna D. (1999). Aspects of material science in food processing: changes in plant cell walls of fruits and vegetables. European Food Research and Technology. 208: 233-250. [DOI: 10.1007/s002170050410] [DOI:10.1007/s002170050410]

22. Manzoor M., Shukla R.N., Mishra A.A., Fatima A., Nayik G.A. (2017). Osmotic dehydration characteristics of pumpkin slices using ternary osmotic solution of sucrose and sodium chloride. Journal of Food Processing and Technology. 8: 669. [DOI: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000669] [DOI:10.4172/2157-7110.1000669]

23. Monteiro R.L., Link J.V., Tribuzi G., Carciofi B.A.M. Laurindo J.B. (2018). Effect of multi-flash drying and microwave vacuum drying on the microstructure and texture of pumpkin slices. LWT-Foods Science Technology. 96: 612-619. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.023] [DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.023]

24. Muhandri T. (2007). The effects of particle size, solid content, NaCl and Na2CO3 on the amilographic characteristics of corn flour and corn starch. Jurnal Teknologi dan Industri Pangan. 18: 109-117.

25. Paradkar V., Sahu G. (2018). Studies on drying of osmotically dehydrated apple slices. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 7: 633-642. [DOI: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.711.077] [DOI:10.20546/ijcmas.2018.711.077]

26. Que F., Mao L., Fang X., Wu T. (2008). Comparison of hot air-drying and freeze-drying on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) flours. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 43: 1195-1201. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01590.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01590.x]

27. Rahman M.M., Gu Y.T., Karim M.A. (2018). Development of realistic food microstructure considering the structural heterogeneity of cells and intercellular space. Food Structure. 15: 9-16. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2018.01.002] [DOI:10.1016/j.foostr.2018.01.002]

28. Ramya V., Jain N.K. (2017). A review on osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: an integrated approach. Journal of Food Process Engineering. 40: 1-22. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpe.12440]. [DOI:10.1111/jfpe.12440]

29. Rodrigues S., Fernandes F.A.N. (2007). Image analysis of osmotically dehydrated fruits: melons dehydration in a ternary system. European Food Research and Technology. 225: 685-691. [DOI: 10.1007/s00217-006-0466-y] [DOI:10.1007/s00217-006-0466-y]

30. Roongruangsri W., Bronlund J.E. (2015). A review of drying processes in the production of pumpkin powder. International Journal of Food Engineering. 11: 789-799. [DOI: 10.1515/ijfe-2015-0168] [DOI:10.1515/ijfe-2015-0168]

31. Silva K.S., Fernandes M.A., Mauro M.A. (2014). Effect of calcium on the osmotic dehydration kinetics and quality of pineapple. Journal of Food Engineering. 134: 37-44. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.02.020] [DOI:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.02.020]

32. Singh J., Singh N. (2003). Studies on the morphological and rheological properties of granular cold water soluble corn and potato starches. Food Hydrocolloids. 17: 63-72. [DOI: 10.1016/S0268-005X(02)00036-X] [DOI:10.1016/S0268-005X(02)00036-X]

33. Tan H.L., Tan T.C., Easa A.M. (2020). Effects of sodium chloride or salt substitutes on rheological properties and water-holding capacity of flour and hardness of noodles. Food Structure. 26: 100154. [DOI: 10.1016/j.foostr.2020.100154] [DOI:10.1016/j.foostr.2020.100154]

34. Tortoe C. (2010). A review of osmodehydration for food industry. African Journal of Food Science. 4: 303-324.

35. Varavinit S., Shobsngob S., Varanyanond W., Chinachoti P., Naivikul O. (2003). Effect of amylose content on gelatinization, retrogradation and pasting properties of flours from different cultivars of thai rice. Starch. 55: 410-415. [DOI: 10.1002/star.200300185] [DOI:10.1002/star.200300185]

36. Yadav A.K., Singh S.V. (2014). Osmotic dehydration of fruits and vegetables: a review. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 51: 1654-1673. [DOI: 10.1007/s13197-012-0659-2] [DOI:10.1007/s13197-012-0659-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

37. Zhang M., Ma J., Li J., Bian H.,Yan Z., Wang D., Xu W., Zhao Y., Shu L. (2023). Influence of NaCl on lipid oxidation and endogenous pro-oxidants/antioxidants in chicken meat. Food Science of Animal Products. 1: 9240010. [DOI: 10.26599/FSAP.2023.9240010]. [DOI:10.26599/FSAP.2023.9240010]

38. Zhang Z., Lyu J., Lou H., Tang C., Zheng H., Chen S., Yu M., Hu W., Jin L., Wang C., Lv H., Lu H. (2021). Effects of elevated sodium chloride on shelf-life and antioxidant ability of grape juice sports drink. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 45: e15049. [DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.15049] [DOI:10.1111/jfpp.15049]

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |