Volume 12, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025, 12(4): 243-262 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jani J, Azizi Suhaili M, Lin C, Mandrinos S. Integrating Mitochondrial 12S rRNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics for Halal Authentication: A Review. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025; 12 (4) :243-262

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1358-en.html

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1358-en.html

Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia, Borneo Medical and Health Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia , jaeyres@ums.edu.my

Full-Text [PDF 962 kb]

(120 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (90 Views)

Full-Text: (11 Views)

Integrating Mitochondrial 12S rRNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics for Halal Authentication: A Review

J. Jani 1,2[*]* , M. Azizi Suhaili 3, C.L.S. Lin 4, S. Mandrinos 5

1. Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

2. Borneo Medical and Health Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

3. Department of Public Health Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

4. Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

5. School of Business Swinburne, University of Technology, 93350 Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

HIGHLIGHTS

Table 1: Several justifications highlighting the effectiveness of the 12S rRNA gene from mitochondrial DNA in the context of halal verification

rRNA=Ribosomal RNA

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages of PacBio sequencing platform

Table 5: Polymerase chain reaction species forward and reverse (5’ to 3’) products

Table 6: Bioinformatics tools for metagenomics analysis in halal authentication

J. Jani 1,2[*]*

1. Department of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

2. Borneo Medical and Health Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

3. Department of Public Health Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

4. Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, 88400 Kota Kinabalu Sabah, Malaysia

5. School of Business Swinburne, University of Technology, 93350 Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

- The mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA gene served as a robust molecular marker for precise species identification in halal authentication.

- Integration of next generation sequencing and third generation sequencing enhanced the accuracy and scalability of halal verification.

- This framework promoted transparency, sustainability, and consumer trust in global halal supply chains.

| Article type Review article |

ABSTRACT This study proposed a molecular framework to ensure compliance with Islamic dietary laws, aligning with the rapidly expanding global halal market projected to reach USD 3 trillion by 2027. The approach integrated mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA sequencing with bioinformatics tools using Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Third-Generation Sequencing (TGS) technologies to facilitate accurate species identification, DNA barcoding, and meet origin authentication. The 12S ribosomal RNA gene provides high precision for species verification due to its conserved yet variable sequence regions. A bioinformatics pipeline incorporating Mothur and QIIME2 was developed to analyse sequencing outputs and validate species Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). This pipeline enhanced traceability and ensured compliance with halal regulatory standards. By detecting even trace residues of non-halal substances, the method strengthens food safety, prevents cross-contamination, and increases consumer trust. The significance of these molecular techniques is in ensuring the safety of food and preventing spoilage. By detecting residues of non-halal substances, this approach addressed significant concerns related to cross-contamination and labelling inaccuracies, enhancing transparency and strengthening consumer trust. Analysing halal certification practices as per industry traditions and international regulatory bodies, as well as the thought-provoking shift to align high-end technologies and foreign experts requires careful harmonisation. This study also focused on factors contributing to that harmonisation. To assess the possible future of halal verification, this review presented a prospective, amalgamating modern science with religious justice to achieve a functional balance and preserve the reliability of halal-validated products. These innovations enable higher levels of precision, transparency, and sustainability, which foster consumer trust and reinvigorate the global marketplace. © 2025, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |

||

| Keywords Certification Mitochondria Bioinformatics Sequence Analysis DNA |

|||

| Article history Received: 20 Apr 2025 Revised: 12 Nov 2025 Accepted: 25 Nov 2025 |

|||

| Abbreviations gDNA=genomic DNA mtDNA=mitochondrial DNA NGS=Next Generation Sequencing ONT=Oxford Nanopore Technologies PCR=Polymerase Chain Reaction PE=Paired End ROI=Region of Interest rRNA=ribosomal RNA TGS=Third Generation Sequencing |

To cite: Jani J., Azizi Suhaili M., Lin C.L.S., Mandrinos S. (2025). Integrating mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatics for halal authentication: a review. Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control. 12: 243-262.

Introduction

Introduction

The Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA, 2022) cited a projection that the global halal market will expand from USD 2 trillion in 2021 to USD 3 trillion (approximately RM 13.3 trillion) by 2027, based on a report by Business Wire. This remarkable growth is fuelled by the rising global Muslim population, which accounts for about 24% of the world’s population, or approximately 1.9 billion people as of 2022. Halal food products encompass several major categories, including meat, poultry, processed seafood, dairy products, cereals and grains, oils and fats, confectionery, and processed fruits and vegetables. The largest demand originates from Asia, followed by the Middle East, Africa, Europe, North America, and Latin America (Shaharuddin et al., 2025). With over 300 global food and beverage companies based in Asia, Malaysia has emerged as a leading hub for halal manufacturing and certification, earning widespread international trust and acceptance for its halal-compliant products (MIDA, 2022; Neequaye et al., 2017).

Malaysia’s halal ecosystem is spearheaded by the Jabatan Agama Islam Malaysia (JAKIM) and the Halal Development Corporation Berhad (HDC), which are responsible for regulatory oversight, certification, and policy development. These agencies align their operations with the Halal Industry Masterplan 2030 to strengthen the nation’s infrastructure and human capital in halal management (Nasir et al., 2021). However, despite Malaysia’s leadership in halal certification, one of the key challenges in maintaining halal authenticity lies in the integration of state-of-the-art technologies for verification and traceability (Hassan et al., 2020).

In this context, the convergence of molecular sequencing and halal verification offers a timely and transformative opportunity. The duality between traditional certification systems and cutting-edge genomic technologies creates both potential and paradoxes that require critical exploration (Garinet et al., 2018). As consumer awareness increases and global supply chains become more complex, ensuring transparency and reliability in halal authentication is no longer feasible through manual inspection and document-based verification alone. Traditional techniques, though valuable, are often time-consuming and inadequate in detecting cross-contamination or fraud in the modern food industry (Amer, 2024).

The emergence of bioinformatics has revolutionised biological data analysis, offering high-throughput, data-centric methods for authenticity verification. Bioinformatics provides computational pipelines capable of analysing large volumes of sequencing data, thereby enabling species identification, DNA barcoding, and halal status determination with unparalleled accuracy (Zou et al., 2023). Studies such as Shen et al. (2022) have demonstrated that bioinformatics-based halal integrity systems improve traceability, enhance food safety, and ensure data-driven decision-making across the supply chain. Applications include mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing for species identification, DNA-based quantification of halal components, and detection of non-halal residues in processed food.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop and propose a comprehensive molecular and computational framework for halal authentication using mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequencing integrated with bioinformatics analysis pipelines such as Mothur and QIIME2. This approach aims to establish a scientifically robust, traceable, and high-throughput system capable of verifying species origin, preventing cross-contamination, and supporting regulatory compliance within the halal supply chain. By aligning genomic science with Islamic dietary law, this study seeks to bridge the gap between modern molecular technologies and traditional halal certification practices, ensuring transparency, sustainability, and consumer confidence in the global halal marketplace.

Ultimately, this study contributes to the future of halal verification by harmonising technological innovation with religious and industrial integrity, thereby positioning bioinformatics as a cornerstone of sustainable halal authentication and global trade assurance (Chen et al., 2023).

Mitochondria and the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene

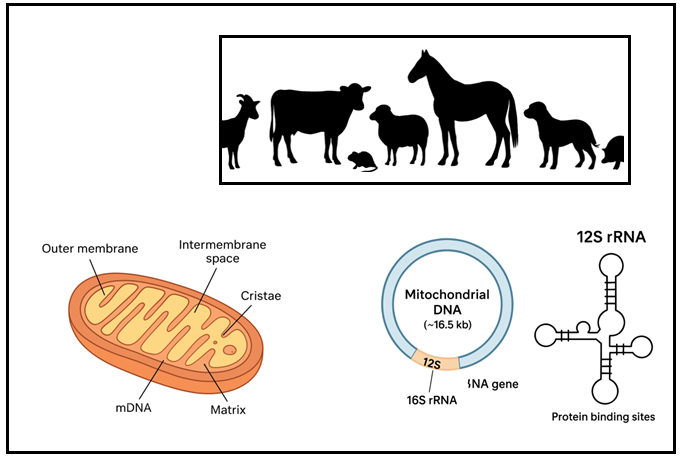

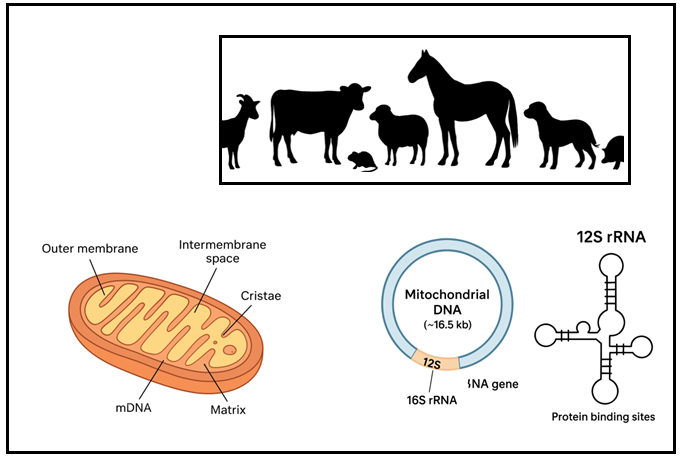

Mitochondria are double-membraned organelles often referred to as the powerhouses of the cell due to their critical role in energy production through oxidative phosphorylation. They possess their own genetic material, known as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is circular and distinct from the nuclear genome (Monzel et al., 2023). mtDNA encodes 13 essential proteins involved in the electron transport chain, along with 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and two rRNAs, namely the 12S and 16S rRNA genes, which are vital for mitochondrial protein synthesis (Figure 1). The unique characteristics of mtDNA, including maternal inheritance, high copy number, lack of recombination, and relatively rapid mutation rate, make it a powerful molecular marker for evolutionary, taxonomic, and forensic studies (Ferreira and Rodriguez, 2024).

Structurally, the mitochondrion comprises an outer membrane that encloses the organelle and an inner membrane folded into cristae, which increases the surface area for ATP synthesis. The space between these membranes is called the intermembrane space, while the innermost compartment, the matrix, contains the mitochondrial genome, ribosomes, and enzymes essential for the citric acid cycle (Absmeier et al., 2023). This semi-autonomous nature allows mitochondria to regulate their own protein synthesis and maintain genetic continuity across generations.

Malaysia’s halal ecosystem is spearheaded by the Jabatan Agama Islam Malaysia (JAKIM) and the Halal Development Corporation Berhad (HDC), which are responsible for regulatory oversight, certification, and policy development. These agencies align their operations with the Halal Industry Masterplan 2030 to strengthen the nation’s infrastructure and human capital in halal management (Nasir et al., 2021). However, despite Malaysia’s leadership in halal certification, one of the key challenges in maintaining halal authenticity lies in the integration of state-of-the-art technologies for verification and traceability (Hassan et al., 2020).

In this context, the convergence of molecular sequencing and halal verification offers a timely and transformative opportunity. The duality between traditional certification systems and cutting-edge genomic technologies creates both potential and paradoxes that require critical exploration (Garinet et al., 2018). As consumer awareness increases and global supply chains become more complex, ensuring transparency and reliability in halal authentication is no longer feasible through manual inspection and document-based verification alone. Traditional techniques, though valuable, are often time-consuming and inadequate in detecting cross-contamination or fraud in the modern food industry (Amer, 2024).

The emergence of bioinformatics has revolutionised biological data analysis, offering high-throughput, data-centric methods for authenticity verification. Bioinformatics provides computational pipelines capable of analysing large volumes of sequencing data, thereby enabling species identification, DNA barcoding, and halal status determination with unparalleled accuracy (Zou et al., 2023). Studies such as Shen et al. (2022) have demonstrated that bioinformatics-based halal integrity systems improve traceability, enhance food safety, and ensure data-driven decision-making across the supply chain. Applications include mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing for species identification, DNA-based quantification of halal components, and detection of non-halal residues in processed food.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop and propose a comprehensive molecular and computational framework for halal authentication using mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequencing integrated with bioinformatics analysis pipelines such as Mothur and QIIME2. This approach aims to establish a scientifically robust, traceable, and high-throughput system capable of verifying species origin, preventing cross-contamination, and supporting regulatory compliance within the halal supply chain. By aligning genomic science with Islamic dietary law, this study seeks to bridge the gap between modern molecular technologies and traditional halal certification practices, ensuring transparency, sustainability, and consumer confidence in the global halal marketplace.

Ultimately, this study contributes to the future of halal verification by harmonising technological innovation with religious and industrial integrity, thereby positioning bioinformatics as a cornerstone of sustainable halal authentication and global trade assurance (Chen et al., 2023).

Mitochondria and the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene

Mitochondria are double-membraned organelles often referred to as the powerhouses of the cell due to their critical role in energy production through oxidative phosphorylation. They possess their own genetic material, known as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is circular and distinct from the nuclear genome (Monzel et al., 2023). mtDNA encodes 13 essential proteins involved in the electron transport chain, along with 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and two rRNAs, namely the 12S and 16S rRNA genes, which are vital for mitochondrial protein synthesis (Figure 1). The unique characteristics of mtDNA, including maternal inheritance, high copy number, lack of recombination, and relatively rapid mutation rate, make it a powerful molecular marker for evolutionary, taxonomic, and forensic studies (Ferreira and Rodriguez, 2024).

Structurally, the mitochondrion comprises an outer membrane that encloses the organelle and an inner membrane folded into cristae, which increases the surface area for ATP synthesis. The space between these membranes is called the intermembrane space, while the innermost compartment, the matrix, contains the mitochondrial genome, ribosomes, and enzymes essential for the citric acid cycle (Absmeier et al., 2023). This semi-autonomous nature allows mitochondria to regulate their own protein synthesis and maintain genetic continuity across generations.

Figure 1: Overview of domestic animal species and mitochondrial DNA structure. Silhouettes depict representative livestock (goat, cattle, horse, sheep, dog, pig, and rat). The lower panels illustrate (left) the mitochondrion and its internal structure, (center) the circular mitochondrial genome (~16.5 kb) showing 12S and 16S rRNA regions, and (right) the secondary structure of 12S rRNA with protein-binding sites.

mDNA=Mitochondrial DNA; rRNA=Ribosomal RNA

mDNA=Mitochondrial DNA; rRNA=Ribosomal RNA

Researchers seldom utilize the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene as a primary marker in molecular studies (Luo et al., 2011). In fact, the normal method of halal validation is based on DNA or protein fragments extracted from specific tissues, such as in the case of meat or food form itself, to ensure they meet Islamic dietary requirements (Ng et al., 2021). The 12S rRNA gene is widely used as a molecular marker for a variety of applications, such as DNA barcoding, phylogenetics, and species identification (Chan et al., 2022). Although DNA-based methods have simple yet useful applications in food authentication and traceability, including halal authentication, they often have limitations in specifically addressing the genetic markers of the species being studied or targeting the presence of forbidden phytochemicals (Muflihah et al., 2023).

With techniques like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), DNA tracking, and real-time PCR, various genetic markers in halal products can be analysed, and authentication for halal status can be granted. These methods have been utilised effectively in determining the source of meat products by assessing some types of mtDNA (Murugaiah et al., 2009). Factors such as the researcher’s aims, and the type of food product being analysed impact on halal authentication technologies and markers (Lubis et al., 2016). Researchers and regulatory authorities typically adopt a combination of scientific approaches and traditional approaches in halal certification methods (Ng et al., 2021).

The 12S rRNA gene, derived from mtDNA, has been identified as an effective target for halal authentication, as shown in Table 1. The specificity of the mitochondrial genome favours species identification, due to maternal inheritance and a higher number of cellular copies than the nuclear DNA (Cahyadi et al., 2020).

With techniques like Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), DNA tracking, and real-time PCR, various genetic markers in halal products can be analysed, and authentication for halal status can be granted. These methods have been utilised effectively in determining the source of meat products by assessing some types of mtDNA (Murugaiah et al., 2009). Factors such as the researcher’s aims, and the type of food product being analysed impact on halal authentication technologies and markers (Lubis et al., 2016). Researchers and regulatory authorities typically adopt a combination of scientific approaches and traditional approaches in halal certification methods (Ng et al., 2021).

The 12S rRNA gene, derived from mtDNA, has been identified as an effective target for halal authentication, as shown in Table 1. The specificity of the mitochondrial genome favours species identification, due to maternal inheritance and a higher number of cellular copies than the nuclear DNA (Cahyadi et al., 2020).

Table 1: Several justifications highlighting the effectiveness of the 12S rRNA gene from mitochondrial DNA in the context of halal verification

| Justifications | Details | References |

| Species Identification | The 12S rRNA gene was examined using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, enabling precise determination of the animal species from which the meat originates. This is crucial for ensuring that the meat is sourced from animals that are halal. | (Zhang et al., 2020) |

| DNA Barcoding | The 12S rRNA gene was used as a DNA barcode for Halal authentication. A reference library of verified 12S rRNA sequences was created from recognised halal species to enable the comparison and confirmation of sample tests. | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) |

| Sequence Variability | Examine variations in the 12S rRNA gene sequence to differentiate between species that are closely related. This can be particularly important in cases where different species might have similar morphological characteristics. | (Chan et al., 2022) |

| Quantitative Analysis |

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) or other methods were used to quantify the amount of mitochondrial DNA, specifically the 12S rRNA gene, in each sample collected. This quantitative approach can provide insights into the composition of meat mixtures. | (Rohman et al., 2022) |

| Authentication of Meat Origin | The authenticity of the declared meat origin was confirmed by comparing the obtained 12S rRNA sequences with reference sequences of known halal animals. This aids in detecting potential adulteration or labelling errors. | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) |

| High-Throughput Screening | The high-throughput capabilities of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Third Generation Sequencing (TGS) were leveraged to process large numbers of samples simultaneously. This is particularly useful for screening meat products in industrial settings or at different points along the supply chain. | (Liu et al., 2021) |

| Validation with Regulatory Standards | The 12S rRNA gene was used to validate halal authentication against established regulatory standards and guidelines. Collaboration with relevant regulatory bodies is necessary to ensure acceptance and recognition of the method. | (Noor et al., 2023) |

| Integration into Existing Certification Processes | The analysis of the 12S rRNA gene was integrated into existing halal certification processes to enhance the accuracy and reliability of halal verification. This ensures alignment with industry practices and standards. | (Van et al., 2012) |

| Cross-validation with Other Molecular Markers | The 12S rRNA gene obtained was cross validated with other molecular markers or methods commonly used in halal certification to strengthen the overall authenticity testing approach. | (Galal-Khallaf, 2021) |

Molecular characterisation of halal authenticity has focused on representative profiles of the meat fraction, with a relative upper trifling ratio found through the latter target (the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene). However, the mitochondrial target of interest has also been the subject of investigation in other studies. The availability of this molecular strategy for sensitive halal authentication in the food industries will be beneficial for researchers and stakeholders who wish to apply it across different thermal processing techniques (Kaveh et al., 2023; Rahman et al., 2023). In addition, the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene serves as a unique molecular marker utilised in sequencing technologies, providing a high-throughput quantitative tool for species identification (Woo et al., 2023), DNA barcoding (Lücking et al., 2020), and meat authentication studies concerning halal certification and compliance with Islamic dietary laws (Aziz et al., 2023). This progress paves the way for a practical and science-based route to authenticating the genuineness and integrity of halal products within the food supply system (Jaswir et al., 2016).

Revolutionising halal verification with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Third Generation Sequencing (TGS) technologies

In recent years, the emergence of high-throughput sequencing platforms such as and TGS has revolutionised the field of genomics. These technologies have enabled the rapid, large-scale acquisition of genetic data, thereby transforming research in areas such as biodiversity, medicine, agriculture, and food authentication. Companies including Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) have played a pivotal role in advancing these platforms, providing comprehensive tools for genome analysis and molecular characterisation across a wide range of species (Liu et al., 2023).

NGS represents a major advancement over conventional Sanger sequencing due to its ability to generate millions of short reads simultaneously, reducing both time and cost. This high-throughput capacity allows for extensive genetic profiling, species identification, and DNA barcoding at an unprecedented resolution. In the context of halal authentication, NGS facilitates the detection of trace DNA sequences from mixed or processed food products, which traditional methods might fail to identify. This makes NGS particularly valuable in verifying the presence or absence of non-halal components, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of halal certification (Aini et al., 2023).

The application of NGS in halal verification offers several advantages. First, it enables species-level identification through targeted sequencing of mitochondrial genes such as 12S rRNA, which are conserved across species but exhibit sufficient variability for precise differentiation. Second, it provides a digital, traceable record of genetic data, thereby increasing transparency and accountability throughout the halal supply chain. Third, when coupled with advanced bioinformatics tools like Mothur and QIIME2, NGS data can be processed, classified, and validated against comprehensive genetic databases to confirm species origin and authenticity with high confidence.

Beyond its technical merits, NGS plays an essential role in strengthening the integrity of halal verification systems by integrating scientific objectivity with religious compliance. By detecting even minute levels of DNA contamination, NGS safeguards against cross-contamination during food processing and enhances consumer trust in certified halal products. Moreover, as the halal market continues to expand globally, NGS provides the scalability and efficiency required to support industrial-scale testing and regulatory enforcement.

In addition to NGS, TGS technologies such as PacBio’s Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore’s nanopore-based platforms further extend analytical capabilities by producing long-read sequences that enable comprehensive genome assembly and structural variant detection. The integration of NGS and TGS technologies offers a hybrid approach, combining the accuracy of short reads with the continuity of long reads to achieve superior precision in species identification and genomic interpretation (Aini et al., 2023). Therefore, the adoption of NGS and TGS technologies in halal verification represents a paradigm shift from conventional biochemical testing towards a molecular, data-driven framework. This scientific evolution not only enhances the credibility and traceability of halal authentication but also aligns Malaysia’s halal certification system with global standards of food safety and technological innovation.

It is important to note that the field of sequencing technologies is constantly evolving, and new advancements may have emerged since the author’s recent update. Also, when selecting a sequencing platform, the specific needs and resources pertinent to the halal industry should be carefully considered.

PacBio sequencing

PacBio, which stands for Pacific Biosciences sequencing, is a TGS method recognised for its long-read capabilities (Rhoads and Au, 2015). This technology has both advantages and disadvantages aspects (Table 2) that are worth considering across various industries, including those related to halal products. The PacBio sequencing platform offers benefits such as high accuracy, extended read lengths, and the ability to characterise complex genomic regions. However, it is essential to consider the associated costs, limitations in throughput, and sample prerequisites in relation to the specific needs and available resources of the halal industry.

Revolutionising halal verification with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Third Generation Sequencing (TGS) technologies

In recent years, the emergence of high-throughput sequencing platforms such as and TGS has revolutionised the field of genomics. These technologies have enabled the rapid, large-scale acquisition of genetic data, thereby transforming research in areas such as biodiversity, medicine, agriculture, and food authentication. Companies including Illumina, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) have played a pivotal role in advancing these platforms, providing comprehensive tools for genome analysis and molecular characterisation across a wide range of species (Liu et al., 2023).

NGS represents a major advancement over conventional Sanger sequencing due to its ability to generate millions of short reads simultaneously, reducing both time and cost. This high-throughput capacity allows for extensive genetic profiling, species identification, and DNA barcoding at an unprecedented resolution. In the context of halal authentication, NGS facilitates the detection of trace DNA sequences from mixed or processed food products, which traditional methods might fail to identify. This makes NGS particularly valuable in verifying the presence or absence of non-halal components, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of halal certification (Aini et al., 2023).

The application of NGS in halal verification offers several advantages. First, it enables species-level identification through targeted sequencing of mitochondrial genes such as 12S rRNA, which are conserved across species but exhibit sufficient variability for precise differentiation. Second, it provides a digital, traceable record of genetic data, thereby increasing transparency and accountability throughout the halal supply chain. Third, when coupled with advanced bioinformatics tools like Mothur and QIIME2, NGS data can be processed, classified, and validated against comprehensive genetic databases to confirm species origin and authenticity with high confidence.

Beyond its technical merits, NGS plays an essential role in strengthening the integrity of halal verification systems by integrating scientific objectivity with religious compliance. By detecting even minute levels of DNA contamination, NGS safeguards against cross-contamination during food processing and enhances consumer trust in certified halal products. Moreover, as the halal market continues to expand globally, NGS provides the scalability and efficiency required to support industrial-scale testing and regulatory enforcement.

In addition to NGS, TGS technologies such as PacBio’s Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore’s nanopore-based platforms further extend analytical capabilities by producing long-read sequences that enable comprehensive genome assembly and structural variant detection. The integration of NGS and TGS technologies offers a hybrid approach, combining the accuracy of short reads with the continuity of long reads to achieve superior precision in species identification and genomic interpretation (Aini et al., 2023). Therefore, the adoption of NGS and TGS technologies in halal verification represents a paradigm shift from conventional biochemical testing towards a molecular, data-driven framework. This scientific evolution not only enhances the credibility and traceability of halal authentication but also aligns Malaysia’s halal certification system with global standards of food safety and technological innovation.

It is important to note that the field of sequencing technologies is constantly evolving, and new advancements may have emerged since the author’s recent update. Also, when selecting a sequencing platform, the specific needs and resources pertinent to the halal industry should be carefully considered.

PacBio sequencing

PacBio, which stands for Pacific Biosciences sequencing, is a TGS method recognised for its long-read capabilities (Rhoads and Au, 2015). This technology has both advantages and disadvantages aspects (Table 2) that are worth considering across various industries, including those related to halal products. The PacBio sequencing platform offers benefits such as high accuracy, extended read lengths, and the ability to characterise complex genomic regions. However, it is essential to consider the associated costs, limitations in throughput, and sample prerequisites in relation to the specific needs and available resources of the halal industry.

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages of PacBio sequencing platform

| Advantages and Disadvantage |

Details | References |

| Accuracy in Genome Sequencing | PacBio sequencing provides high accuracy in genome sequencing, which is crucial for identifying and verifying the genetic makeup of organisms relevant to the halal industry. | (Rhoads and Au, 2015) |

| Long Read Lengths | PacBio sequencing produces long reads, enabling the sequencing of entire genes or even entire genomes without the need for assembly from short reads. This is beneficial for accurately identifying and characterising specific genes or regions of interest. | (Hook and Timp, 2023) |

| Detection of Genetic Variations | The long-read lengths facilitate the detection of genetic variations, such as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variations. This is important in ensuring the authenticity and genetic integrity of halal products. | (Bannor et al., 2023; Sajali et al., 2020) |

| Characterisation of Complex Genomic Regions | PacBio sequencing is well-suited for characterising complex genomic regions, including repetitive elements and structural variations, which can be challenging for other sequencing technologies. This is valuable for a comprehensive understanding of genetic traits in halal-relevant organisms. | (Rhoads and Au, 2015) |

| Cost | PacBio sequencing is more expensive compared to other sequencing technologies. This can be a limiting factor, especially for large-scale genomic studies in the halal industry. | (Teng et al., 2017) |

| Throughput | While PacBio sequencing provides long reads, its throughput can be lower compared to other sequencing platforms. This limitation may impact the speed at which large-scale genomic data can be generated. | (Amarasinghe et al., 2020) |

| Error Rate | Although PacBio sequencing has made progress in accuracy, it may still show a greater incidence of errors when compared with some short-read sequencing technologies. This can be a concern when precise genetic information is crucial for halal certification. | (Oehler et al., 2023; Sedlazeck et al., 2018) |

| Sample Requirements | PacBio sequencing may have specific sample conditions, and the challenge of sourcing high-quality DNA from certain types of samples may restrict its applicability in the halal industry. | (De Coster et al., 2021; Haynes et al., 2019) |

ONT sequencing

The concept of “MinION sequencing” likely refers to sequencing performed using the MinION sequencer from ONT. ONT offers a portable DNA and RNA sequencing platform that utilises nanopore technology for real-time analysis. There are several advantages and disadvantages of ONT sequencing, as shown in Table 3.

The concept of “MinION sequencing” likely refers to sequencing performed using the MinION sequencer from ONT. ONT offers a portable DNA and RNA sequencing platform that utilises nanopore technology for real-time analysis. There are several advantages and disadvantages of ONT sequencing, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Advantages and disadvantages of ONT sequencing platform

ONT=Oxford Nanopore Technologies

| Advantages and Disadvantages | Details | References |

| Real-Time Sequencing | The ONT sequencing provides real-time data, allowing for rapid analysis and decision-making. This can be beneficial in the halal industry for quick verification of the genetic makeup of organisms or products. | (Tyler et al., 2018) |

| Portability | The ONT sequencer is portable and relatively small, making it suitable for field applications. This can be advantageous in situations where on-site sequencing is needed, such as in remote areas or at production facilities in the halal industry. | (Wasswa et al., 2022) |

| Long Read Lengths | Similar to PacBio sequencing, ONT sequencing also offers long read lengths. This is advantageous for accurately characterising genes and genomic regions relevant to the halal industry without the need for assembly. | (Udaondo et al., 2021) |

| Ease of Use | The ONT sequencer is known for its user-friendly interface and simplified workflow. This can be advantageous in settings where technical expertise may be limited, such as in small-scale halal production facilities. | (King et et al., 2020; Wasswa et al., 2022) |

| Cost-Effective for Small-Scale Projects | The ONT sequencer has relatively low upfront costs compared to some other sequencing technologies. This makes it potentially cost-effective for small-scale projects or applications in the halal industry with limited budgets. | (Chang et al., 2020; Wasswa et al., 2022) |

| Error Rates | Nanopore sequencing technologies, including ONT, have historically had higher error rates compared to some other sequencing platforms. While error rates have improved over time, accuracy may still be a concern, especially for applications requiring precise genetic information. | (Sun et al., 2022) |

| Throughput | While ONT sequencing is suitable for small-scale projects, it may have limitations in terms of throughput for large-scale genomic studies. High-throughput sequencing technologies may be more appropriate for large-scale applications in the halal industry. | (Haynes et al., 2019; Wasswa et al., 2022) |

| Sample Contamination | Nanopore sequencing is sensitive to sample quality, and contamination can affect the accuracy of results. Ensuring high-quality DNA is essential for reliable sequencing, which may be a consideration in the halal industry where sample quality can vary. | (Haynes et al., 2019; Noakes et al., 2019) |

| Data Storage and Analysis | The real-time nature of ONT sequencing generates large amounts of data, and handling and analysing this data may require advanced computational resources. This can be a consideration for facilities with limited bioinformatics capabilities in the halal industry. | (Cao et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016) |

Illumina sequencing

Illumina sequencing represents a leading technology in NGS that has established itself as a standard in genomics research. Table 4 outlines some potential advantages and disadvantages of applying Illumina sequencing within the halal industry.

Given its high accuracy, particularly when combined with other applications, along with its high throughput and versatility, Illumina sequencing holds undeniable promise for many applications in the halal sector, particularly those that require fast and reliable analysis (Meyer and Kircher, 2010). Still, the limited read lengths, size of the instrument, and associated costs must all be weighed according to the specific requirements of genomic assays.

The ultimate decision is and should be application-based, with sequencing technology selected based on the unmet needs and the unique requirements of the halal industry. Considering that PacBio sequencing is capable of generating long reads, it is particularly useful for characterising complex genomic regions and variations (Karst et al., 2021) making it a valuable tool for complete genomic characterisation. Conversely, if the application involves real-time data analytics or requires mobility, ONT sequencing is a more compact and portable option. However, it is important to note that this approach has a lower output and a higher error rate. With its combination of accuracy, throughput, and cost, Illumina sequencing has become particularly beneficial, enabling a wide array of high-throughput applications and providing researchers with a wide versatility of applications to serve their needs.

Given the variety of options available, the prevailing view among researchers is that a hybrid approach, using multiple sequencing technologies can leverage the strengths of each platform for a more holistic analysis (Jovic et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the sequence data itself, along with financial and logistical planning for specific projects, will ultimately determine the best sequencing method to accommodate the specific needs of halal authenticity testing.

Illumina sequencing represents a leading technology in NGS that has established itself as a standard in genomics research. Table 4 outlines some potential advantages and disadvantages of applying Illumina sequencing within the halal industry.

Given its high accuracy, particularly when combined with other applications, along with its high throughput and versatility, Illumina sequencing holds undeniable promise for many applications in the halal sector, particularly those that require fast and reliable analysis (Meyer and Kircher, 2010). Still, the limited read lengths, size of the instrument, and associated costs must all be weighed according to the specific requirements of genomic assays.

The ultimate decision is and should be application-based, with sequencing technology selected based on the unmet needs and the unique requirements of the halal industry. Considering that PacBio sequencing is capable of generating long reads, it is particularly useful for characterising complex genomic regions and variations (Karst et al., 2021) making it a valuable tool for complete genomic characterisation. Conversely, if the application involves real-time data analytics or requires mobility, ONT sequencing is a more compact and portable option. However, it is important to note that this approach has a lower output and a higher error rate. With its combination of accuracy, throughput, and cost, Illumina sequencing has become particularly beneficial, enabling a wide array of high-throughput applications and providing researchers with a wide versatility of applications to serve their needs.

Given the variety of options available, the prevailing view among researchers is that a hybrid approach, using multiple sequencing technologies can leverage the strengths of each platform for a more holistic analysis (Jovic et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the sequence data itself, along with financial and logistical planning for specific projects, will ultimately determine the best sequencing method to accommodate the specific needs of halal authenticity testing.

Table 4: Advantages and disadvantages of Illumina sequencing platform

| Advantages and Disadvantages | Details | References |

| High Accuracy | Illumina sequencing is known for its high accuracy, which is crucial for obtaining reliable genetic information. This accuracy is important in halal industry applications, such as the identification and verification of specific genetic traits in organisms. | (Haynes et al., 2019; Muflihah et al., 2023) |

| High Throughput | The Illumina platforms typically offer high throughput, allowing for the simultaneous sequencing of multiple samples. This is advantageous for large-scale genomic studies in the halal industry, where the analysis of a significant number of samples may be required. | (Reuter et al., 2015) |

| Cost-Effective for High-Throughput Applications | Illumina sequencing is often considered cost-effective for high-throughput projects. The cost per base pair is relatively low, making it suitable for projects in the halal industry that require extensive genomic coverage. | (Satam et al., 2023) |

| Wide Range of Applications | Illumina sequencing platforms are versatile and can be used for various applications, including whole-genome sequencing, RNA sequencing, and targeted sequencing. This flexibility allows researchers in the halal industry to choose the most suitable approach for their specific needs. | (Haynes et al., 2019) |

| Established Protocols and Workflows | Illumina sequencing has been widely adopted in the scientific community, and there are well-established protocols and workflows. This can simplify the sequencing process and make it more accessible, even in settings with limited expertise in genomics. | (Satam et al., 2023) |

| Short Read Lengths | One limitation of Illumina sequencing is the relatively short read lengths compared to some other sequencing technologies. This may pose challenges when trying to sequence through repetitive or complex genomic regions in the halal industry. | (Bianconi et al., 2023) |

| Instrument Size | Some Illumina sequencers may be larger and less portable compared to certain portable sequencing technologies. If on-site or field sequencing is required in the halal industry, the size and portability of the sequencer could be a consideration. | (Guptaand Verma, 2019; Slatko et al., 2018) |

| Error Rate in Homopolymeric Regions | Illumina sequencing can have difficulties accurately sequencing homopolymeric regions (repeated sequences of the same nucleotide). This may be a concern in applications where these regions are relevant, such as in the analysis of certain genes in the halal industry. | (Moorthie et al., 2011) |

| Complex Library Preparation | The library preparation for Illumina sequencing can be more complex compared to some other sequencing platforms. This may add an extra step and potentially increase the chances of errors or contamination in the halal industry workflow. | (Yang et al., 2014) |

| Instrument Costs | While Illumina sequencing can be cost-effective for high-throughput applications, the upfront costs of purchasing the sequencing instruments can be relatively high. This may be a consideration for facilities with limited budgets in the halal industry. | (Dunham and Friesen, 2013) |

Design of specialised primers intended for the identification of the 12S rRNA gene

The PCR technique is typically carried out to selectively amplify the 12S rRNA genes from the extracted DNA. Several primers can be proposed for use in a multiplex setup of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene, as shown in Table 5. Within these primers, there exists a universal sequence that targets the Region of Interest (ROI).

The PCR technique is typically carried out to selectively amplify the 12S rRNA genes from the extracted DNA. Several primers can be proposed for use in a multiplex setup of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene, as shown in Table 5. Within these primers, there exists a universal sequence that targets the Region of Interest (ROI).

Table 5: Polymerase chain reaction species forward and reverse (5’ to 3’) products

| Animals | Sequences | Base pair (bp) | References |

| Goat | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-CTCGACAAATGTGAGTTACAGAGGGA-3’ |

157 | (Matsunaga et al., 1999) |

| Chicken | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-AAGATACAGATGAAGAAGAATGAGGCG-3’ |

227 | (Matsunaga et al., 1999) |

| F 5’-TTCTTCGGACACCCCGAAG-3’ R 5’-CTAGGCCCAGGAAATGTT-3’ |

596 | (Boyrusbianto et al., 2023) | |

| Cattle | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-CTAGAAAAGTGTAAGACCCGTAATATAAG-3’ |

274 | (Matsunaga et al., 1999) |

| Sheep | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-CTATGAATGCTGTGGCTATTGTCGCA-3’ |

331 | (Matsunaga et al., 1999) |

| Horse | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-CTCAGATTCACTCGACGAGGGTAGTA-3’ |

439 | (Matsunaga et al., 1999) |

| Rat | F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-GAATGGGATTTTGTCTGCGTTGGAGTTT-3’ |

603 | (Matsunaga et al.,1999; Nuraini et al., 2012) |

| F 5’-ACCGCGGTCATACGATTAAC-3’ R 5’-TCTGGGAAAAGAAAATGTAGCC-3’ |

491 | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) | |

| Bovine | F 5’-ACCGCGGTCATACGATTAAC-3’ R 5’-AGTGCGTCGGCTATTGTAGG-3’ |

155 | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) |

| F 5’-TTCTTCGGACACCCCGAAG-3’ R 5’-CGGTTGGAATAGCAATAA-3’ |

263 | (Boyrusbianto et al., 2023) | |

| Dog | F 5’-ACCGCGGTCATACGATTAAC-3’ R 5’-TCCTCTGGCGAATTATTTTGTTG-3’ |

244 | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) |

| Pig | F 5’-ACCGCGGTCATACGATTAAC-3’ R 5’-GAATTGGCAAGGGTTGGTAA-3’ |

357 | (Cahyadi et al., 2020) |

| F 5’-TTCTTCGGACACCCCGAAG-3’ R 5’-TGGTGAGCCCATACGATA-3’ |

168 | (Boyrusbianto et al., 2023) | |

| F 5’-GACCTCCCAGCTCCATCAAACATCTCATCTTGATGAAA-3’ R 5’-CTGATAGTAGATTTGTGATGACCGTA-3’ |

398 |

(Matsunaga et al., 1999) | |

| F 5’-AACCCTATGTACGTCGTGCAT-3’ R 5’-ACCATTGACTGAATAGCACCT-3’ |

531 | (Monteil-Sosa et al., 2000; Sahilah et al 2011) | |

| Primers universal | F 5’- AAACTGGGATTAGATACCCCACTA -3’ R 5’-GAGGGTGACGGGCGGTGTGT-3’ |

456 | (Pandey et al., 2007; Sahilah et al., 2011) |

Table 5 summarises the forward and reverse primer sequences used for PCR-based species identification, specifically targeting various animal species relevant to halal authentication. The table lists the primers, expected PCR product sizes (in base pairs, bp), and corresponding references, demonstrating the diversity of genetic markers used across different studies.

The table includes primers for multiple commonly consumed animals such as goat, chicken, cattle, sheep, horse, rat, dog, and pig. These species are frequently tested in halal verification to ensure the absence of non-halal ingredients or cross-contamination in food products. In addition, universal primers are included, which target conserved regions of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene and can amplify DNA across multiple vertebrate species.

Each primer set is associated with an expected amplicon size, which ranges from 155 bp (bovine) to 603 bp (rat), depending on the species and the genetic region targeted. Shorter amplicons are often preferred for processed food products, where DNA may be partially degraded. Longer amplicons may provide higher specificity in differentiating closely related species. For instance, the chicken primers produce amplicons of 227 bp and 596 bp, allowing flexibility depending on the sample type and quality.

The type of sample analysed using these primers can include raw meat, processed food, mixed meat products, or highly processed ingredients, all of which are relevant in halal authentication. The number of samples tested in each study may vary, but PCR amplification with these primers provides a rapid, sensitive, and species-specific method for detecting halal or non-halal components. For example, primers designed for pig DNA (non-halal) are critical for identifying contamination in food products labelled as halal.

References in Table 5 highlight the original sources where these primers were developed or validated, such as Matsunaga et al. (1999), Cahyadi et al. (2020), and Boyrusbianto et al. (2023). These studies demonstrated the reliability and reproducibility of these primers for molecular authentication. By integrating these primers into a PCR or sequencing workflow, halal verification can be performed accurately and efficiently, enabling both regulatory compliance and consumer confidence.

Overall, Table 5 illustrates the comprehensive set of primers available for PCR-based species identification, supporting the use of mtDNA markers such as 12S rRNA for halal authentication across a wide range of food products.

Optimising PCR amplification for high-quality sequencing across Illumina, PacBio, and ONT platforms

PCR amplification is a major process to enhance sequencing outputs for platforms such as Illumina, PacBio, and ONT. This step measures that the target ROI, like the 12S rRNA gene from genomic DNA (gDNA) input, is present in the proper quantity and quality, as both are essential for fetching high and reliable sequencing results (Kayama et al., 2021). Specific primers can be used to improve the selective amplification of target sequence, concentrating sequencing activity in the ROI and achieving high coverage, even for low-abundance regions (Ye et al., 2012).

The first steps of such a workflow typically involve the use of DNA extraction kits and protocols that protect DNA integrity (Dubois et al., 2022). From here, high-quality gDNA is used as an input for PCR amplification (Schloss et al., 2011). Next, primers are designed for the target ROI. For example, in the case of the 12S rRNA gene, primers are strategically chosen to bind conserved sequences flanking the target region, thereby clinching specificity (Woo et al., 2023). On the Illumina platform, primers are designed to amplify shorter DNA fragments (ranging from 250 to 300 bp) to ensure compatibility with the minimum read length required for Paired End (PE) sequencing (Kozich et al., 2013). On the other hand, large amplicon sequencing technologies (hundreds to a few kilobases), such as PacBio and ONT use primers designed to amplify the large amplicons, taking advantage of their long-read capabilities (Liu et al., 2020).

The cycle of denaturation, annealing, and extension is then repeated to achieve exponential amplification of the target genetic sequence (Nichols and Quince, 2016). The number of cycles is optimised based on the starting gDNA quantity and the desired amplicon length. Then, the amplified PCR products are purified to remove unincorporated primers, nucleotides, and other contaminants that might adversely affect sequencing. With long-read technologies, size selection is also applicable to ensure that the amplicons are of optimal size for sequencing. Depending on the platform, the next step of library preparation differs. For Illumina sequencing, the putative amplicons are ligated with platform-specific adapters, which ultimately form a sequencing library to be sequenced via PE or single-end (SE) strategies (Callahan et al., 2016). In a different approach, the PacBio and ONT libraries apply the ligation of adapters onto the amplified amplicons to prime them for long-read sequencing. Long-read platforms excel at resolving challenging areas, such as repeat elements and whole-gene analysis, including the 12S rRNA.

Once the sequencing libraries are ready, data generation begins. The second approach employed by Illumina is high-throughput, short-read sequencing, which delivers highly accurate data but often needs overlapping PE reads to cover the entire area of interest (Callahan et al., 2016). PacBio and ONT, on the other hand, use long-read sequencing methods that allow them to capture entire regions in a single pass, leading to easier assembly and more accurate mapping of challenging genomic regions. While gDNA serves the same fundamental role across all sequencing platforms, differences exist in the specific amplification and sequencing processes used (Woltyńska et al., 2023). PCR amplification enriches the signal of the desired sequence to achieve sufficient flow-cell coverage necessary for quality sequencing. Optimising workflows for respective platforms maximises sequencing potential, particularly in regions such as the 12S rRNA gene (Cahyadi et al., 2020). This includes Illumina short-read sequencing technology, which provides high throughput over small DNA fragments (Callahan et al., 2016). Meanwhile, long-read sequencing through PacBio and ONT offers better identification of structural variants and improved resolution of complex genomic segments (Ahsan et al., 2023).

To summarise, PCR amplification is an enabling step in sequencing workflows, enabling technologies, such as Illumina, PacBio, and ONT for a variety of applications. Non-Long Terminal Repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons could certainly interfere with PCR amplification and reduce sequencing yields, though PCR remains essential for enriching target regions as well as ensuring a reliable sequence of interest. By implementing a bespoke amplification process, sequencing platforms have expanded their applications in species identification, phylogenetics, and mitochondrial genome studies (Schloss et al., 2011).

Short-read versus long-read sequencing: a comprehensive approach to 12S rRNA analysis for bioinformatics

It is widely known that Illumina sequencing technology boasts high throughput and outstanding accuracy, thus making it an optimal platform for producing short reads to cover target sequences, even when they do not exceed 500 bp (Kozich et al., 2013). Two-read analysis on mitochondrial 12S rRNA using Illumina’s PE sequencing format for 250 PE or 300 PE reads has been performed (Prakrongrak et al., 2023). However, the short-read property of Illumina sequencing makes it difficult to merge overlaps from PE reads simply, hence it typically needs to be preceded by tools like FLASH, PEAR, or BBMerge. These tools perform synchronisation and merging of the complementary reads to reconstruct the sequence of the entire target in question while ensuring that everything is covered correctly with minimal or no gaps or assembly variants. Such methods improve downstream bioinformatics analyses by providing better sequence resolution, even in moderately complex regions (Borodinov et al., 2022).

Illumina's short-read sequencing excels in its accuracy, with Phred quality scores (Q-scores) commonly above Q30 along most of the read length (indicating an error rate of approximately <1%) (Jani et al., 2023; Thomas and Hahn, 2019). The PE strategy provides complementary reads at the two ends of the target DNA fragment, enabling error correction during PE base-calling and mitigating uncertainties. Additionally, the high sequencing depth of the platform guarantees significant read redundancy, which aids in detecting low-frequency variants and enables accurate allele identification. The confidence gained from such an analysis is largely due to the strength of the signal generated by the target gene, such as 12S rRNA, making it particularly sound for targeted sequencing applications (Woo et al., 2023). While read length has an inherent limit due to the chemistry of Illumina’s sequencing method, Illumina provides a great compromise of accuracy, throughput, and low-end cost that together positions its technology as highly suitable for use in 12S rRNA sequencing workflows (Woo et al., 2023).

Due to the acquisition of whole gene-spanning reads in a single sequence, long-read sequencing technologies like PacBio and ONT have significant advantages for analysing 12S rRNA genes (Cahyadi et al., 2020). Because of this extensive coverage, time-consuming assembly steps like merging overlapping reads, a necessity in Illumina workflows, are off the table. In particular, long-read sequencing is well suited for resolving structural variants or guanine-cytosine-rich (GC-rich) or repetitive regions of the 12S rRNA gene, as many short-read platforms often struggle to achieve adequate mapping in these regions (Wenger et al., 2019). In addition, long read sequencing can mitigate the biases in library preparation steps (for example, shearing and PCR amplification) that are commonly encountered in Illumina workflows (Bohmann et al., 2022). Historically, long-read technologies like ONT exhibit greater base-calling errors when compared to Illumina (Ma et al., 2019; Wick et al., 2023) though emerging technologies such as PacBio HiFi sequencing have brought this gap to a narrow. The long reads provided by PacBio HiFi now match the high-quality Phred scores of Illumina’s short reads, in addition to greater read length and accuracy.

The benefits of long-read sequencing in 12S rRNA sequencing are unequivocal for applications that require full-gene resolution (Zhou et al., 2023), such as species identification, genealogical analysis, or mitochondrial heteroplasmy detection. Long-read technologies afford full coverage of the target region and therefore contribute to the reduction of ambiguity and increase confidence in downstream analyses. Although short-read platforms are a cost-effective solution for high-throughput and targeted applications, long-read sequencing is indispensable for acquiring nuanced and complete sequence information for the 12S rRNA gene.

Both short- and long-read sequencing technologies have unique advantages for 12S rRNA sequencing. Illumina is the best option with respect to accuracy, cost efficiency, and high throughput capability, making it the best option for monogenic assays and identifying single variant genes. On the flip side, long-read technologies such as PacBio and ONT are needed for complete analyses requiring full-gene resolution and structural information and thus represent an evolution of meta-analysis capabilities within bioinformatics data analysis.

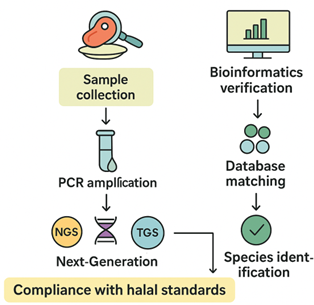

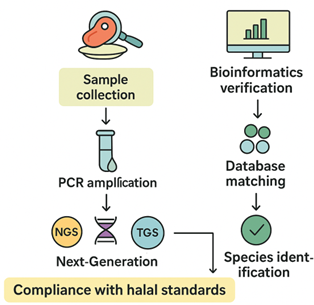

Figure 2: The streamlined workflow for molecular halal verification through mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

NGS=Next Generation Sequencing; PCR=Polymerase Chain Reaction; TGS=Third Generation Sequencing

Figure 2 illustrates the streamlined workflow for molecular halal verification through mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. The process begins with sample collection followed by PCR amplification of the 12S rRNA gene. The amplified DNA is then subjected to either NGS or TGS platforms to obtain high-resolution sequence data. The resulting sequences are processed through bioinformatics verification, where reads are matched against reference databases to achieve species identification. This molecular approach ensures accurate and reliable compliance with halal standards, enhancing transparency and traceability within the halal authentication process.

Streamlined sequencing for precision and reliability: advancing mitochondrial 12S rRNA analysis in industrial halal authentication

Next, because Illumina sequencing generates hundreds of short reads, the PE reads must be merged and undergo quality checks before being used in most downstream analytical tools, such as QIIME2 or Mothur (Meyer and Kircher, 2010). Thus, there is a step where overlapping read pairs are merged using special algorithms, followed by a quality-filtering step that removes low-quality bases and reads with performing errors. These operations provide a clean and reliable data source for the analyses that follow.

On the other hand, long-read sequencing systems, such as PacBio and ONT, directly sequence the amplified target region and generate long, continuous reads that cover the entire ROI (Wenger et al., 2019). Since these single reads span the entire targeted sequence, quality checking in long-read sequencing requires little verification. This streamlined pipeline reduces data preparation concerns, speeding up analytical operations and minimises the need for additional sequence processing.

The analysis of mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequencing consists of multiple interrelated steps and is facilitated by modern computational tools to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of results within a commercial halal authenticity testing pipeline (Yang et al., 2014). First, the pre-processing of data: Illumina sequenced data are trimmed and filtered to remove low-quality reads and adapter sequences. Bioinformatics pipelines typically apply tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt at this point to clean the data and retain only high-quality reads for downstream analysis (Chen et al., 2018).

However, PacBio and ONT follow a similar systematic workflow, enabled by their long-read sequencing technologies. The ability to sequence the whole target region in one read, without the need for a read assembly, enhances the accuracy of variant detection (Uliano-Silva et al. 2023). Usually, after the quality check of Illumina, PacBio, and ONT platform data, the next step is to run software for downstream analysis such as QIIME2 or Mothur (Hernández and Guzmán, 2023). These tools help in taxonomic classification, sequence alignment, and variant detection. These are specific to Illumina's workflows and may range from different merging and quality-filtering of PE reads so as to get higher-quality short reads for further processing (Bolger et al., 2014). In contrast, both PacBio and ONT are capable of sequencing the entire 12S rRNA gene in a single read, which simplifies the pipeline and reduces the complexity of data interpretation (Roy et al., 2022). These platforms excel at resolving complex or repetitive regions, which can be quite challenging for short-read technologies.

All three technologies (Illumina, PacBio, ONT) have their own set of strengths. The continuous long fragments produced by PacBio and ONT improve the specificity and efficiency of 12S rRNA mitochondrial sequencing even though Illumina generates highly accurate short reads (El-Nabi et al., 2021). This means that the convergence of these technologies is especially well suited for the large-scale application of halal authenticity testing as it provides a comprehensive olive branch to large-scale sequencing capabilities.

Then reports are produced, making it very clear what the actual findings are, including what species have been detected, at what level of confidence, and where the halal profile appears to differ from the expected halal profile. They consist of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) associated with each sample alongside descriptive data such as phylogenetic trees and relevant metadata (Venkatas and Adeleke, 2019). This increases the transparency and potential impact for stakeholders to utilise in making data-driven decisions from the analysis.

One of the first sequence data selected in a bioinformatics pipeline using the interspecies variability and intraspecies conservativeness of the 12S rRNA gene, a widely used mitochondrial marker provided strong resolution for distinguishing between species (Woo et al., 2023). This high-throughput approach, combining advanced sequencing technologies in a connected computational framework, offers assurances of precision and reproducibility.

Many pipelines are available to help run through the stages of the analysis. This has been carried out for quality control (Aksamentov et al., 2021), sequence alignment (Katoh et al., 2017), taxonomic classification (Menzel et al., 2016), Operational Taxonomic Unit (out) assignment (Wang et al., 2011) and final reporting (Taber, 2017). All pipelines were purpose-built to interface compatibly with the sequencing platform utilised (Wang et al., 2023) to enable data processing from initial sequencing reads to actionable results (Pillay et al., 2022). Other bioinformatics tools are also summarised in Table 6, which have been used for halal authentication analysis.

The table includes primers for multiple commonly consumed animals such as goat, chicken, cattle, sheep, horse, rat, dog, and pig. These species are frequently tested in halal verification to ensure the absence of non-halal ingredients or cross-contamination in food products. In addition, universal primers are included, which target conserved regions of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene and can amplify DNA across multiple vertebrate species.

Each primer set is associated with an expected amplicon size, which ranges from 155 bp (bovine) to 603 bp (rat), depending on the species and the genetic region targeted. Shorter amplicons are often preferred for processed food products, where DNA may be partially degraded. Longer amplicons may provide higher specificity in differentiating closely related species. For instance, the chicken primers produce amplicons of 227 bp and 596 bp, allowing flexibility depending on the sample type and quality.

The type of sample analysed using these primers can include raw meat, processed food, mixed meat products, or highly processed ingredients, all of which are relevant in halal authentication. The number of samples tested in each study may vary, but PCR amplification with these primers provides a rapid, sensitive, and species-specific method for detecting halal or non-halal components. For example, primers designed for pig DNA (non-halal) are critical for identifying contamination in food products labelled as halal.

References in Table 5 highlight the original sources where these primers were developed or validated, such as Matsunaga et al. (1999), Cahyadi et al. (2020), and Boyrusbianto et al. (2023). These studies demonstrated the reliability and reproducibility of these primers for molecular authentication. By integrating these primers into a PCR or sequencing workflow, halal verification can be performed accurately and efficiently, enabling both regulatory compliance and consumer confidence.

Overall, Table 5 illustrates the comprehensive set of primers available for PCR-based species identification, supporting the use of mtDNA markers such as 12S rRNA for halal authentication across a wide range of food products.

Optimising PCR amplification for high-quality sequencing across Illumina, PacBio, and ONT platforms

PCR amplification is a major process to enhance sequencing outputs for platforms such as Illumina, PacBio, and ONT. This step measures that the target ROI, like the 12S rRNA gene from genomic DNA (gDNA) input, is present in the proper quantity and quality, as both are essential for fetching high and reliable sequencing results (Kayama et al., 2021). Specific primers can be used to improve the selective amplification of target sequence, concentrating sequencing activity in the ROI and achieving high coverage, even for low-abundance regions (Ye et al., 2012).

The first steps of such a workflow typically involve the use of DNA extraction kits and protocols that protect DNA integrity (Dubois et al., 2022). From here, high-quality gDNA is used as an input for PCR amplification (Schloss et al., 2011). Next, primers are designed for the target ROI. For example, in the case of the 12S rRNA gene, primers are strategically chosen to bind conserved sequences flanking the target region, thereby clinching specificity (Woo et al., 2023). On the Illumina platform, primers are designed to amplify shorter DNA fragments (ranging from 250 to 300 bp) to ensure compatibility with the minimum read length required for Paired End (PE) sequencing (Kozich et al., 2013). On the other hand, large amplicon sequencing technologies (hundreds to a few kilobases), such as PacBio and ONT use primers designed to amplify the large amplicons, taking advantage of their long-read capabilities (Liu et al., 2020).

The cycle of denaturation, annealing, and extension is then repeated to achieve exponential amplification of the target genetic sequence (Nichols and Quince, 2016). The number of cycles is optimised based on the starting gDNA quantity and the desired amplicon length. Then, the amplified PCR products are purified to remove unincorporated primers, nucleotides, and other contaminants that might adversely affect sequencing. With long-read technologies, size selection is also applicable to ensure that the amplicons are of optimal size for sequencing. Depending on the platform, the next step of library preparation differs. For Illumina sequencing, the putative amplicons are ligated with platform-specific adapters, which ultimately form a sequencing library to be sequenced via PE or single-end (SE) strategies (Callahan et al., 2016). In a different approach, the PacBio and ONT libraries apply the ligation of adapters onto the amplified amplicons to prime them for long-read sequencing. Long-read platforms excel at resolving challenging areas, such as repeat elements and whole-gene analysis, including the 12S rRNA.

Once the sequencing libraries are ready, data generation begins. The second approach employed by Illumina is high-throughput, short-read sequencing, which delivers highly accurate data but often needs overlapping PE reads to cover the entire area of interest (Callahan et al., 2016). PacBio and ONT, on the other hand, use long-read sequencing methods that allow them to capture entire regions in a single pass, leading to easier assembly and more accurate mapping of challenging genomic regions. While gDNA serves the same fundamental role across all sequencing platforms, differences exist in the specific amplification and sequencing processes used (Woltyńska et al., 2023). PCR amplification enriches the signal of the desired sequence to achieve sufficient flow-cell coverage necessary for quality sequencing. Optimising workflows for respective platforms maximises sequencing potential, particularly in regions such as the 12S rRNA gene (Cahyadi et al., 2020). This includes Illumina short-read sequencing technology, which provides high throughput over small DNA fragments (Callahan et al., 2016). Meanwhile, long-read sequencing through PacBio and ONT offers better identification of structural variants and improved resolution of complex genomic segments (Ahsan et al., 2023).

To summarise, PCR amplification is an enabling step in sequencing workflows, enabling technologies, such as Illumina, PacBio, and ONT for a variety of applications. Non-Long Terminal Repeat (non-LTR) retrotransposons could certainly interfere with PCR amplification and reduce sequencing yields, though PCR remains essential for enriching target regions as well as ensuring a reliable sequence of interest. By implementing a bespoke amplification process, sequencing platforms have expanded their applications in species identification, phylogenetics, and mitochondrial genome studies (Schloss et al., 2011).

Short-read versus long-read sequencing: a comprehensive approach to 12S rRNA analysis for bioinformatics

It is widely known that Illumina sequencing technology boasts high throughput and outstanding accuracy, thus making it an optimal platform for producing short reads to cover target sequences, even when they do not exceed 500 bp (Kozich et al., 2013). Two-read analysis on mitochondrial 12S rRNA using Illumina’s PE sequencing format for 250 PE or 300 PE reads has been performed (Prakrongrak et al., 2023). However, the short-read property of Illumina sequencing makes it difficult to merge overlaps from PE reads simply, hence it typically needs to be preceded by tools like FLASH, PEAR, or BBMerge. These tools perform synchronisation and merging of the complementary reads to reconstruct the sequence of the entire target in question while ensuring that everything is covered correctly with minimal or no gaps or assembly variants. Such methods improve downstream bioinformatics analyses by providing better sequence resolution, even in moderately complex regions (Borodinov et al., 2022).

Illumina's short-read sequencing excels in its accuracy, with Phred quality scores (Q-scores) commonly above Q30 along most of the read length (indicating an error rate of approximately <1%) (Jani et al., 2023; Thomas and Hahn, 2019). The PE strategy provides complementary reads at the two ends of the target DNA fragment, enabling error correction during PE base-calling and mitigating uncertainties. Additionally, the high sequencing depth of the platform guarantees significant read redundancy, which aids in detecting low-frequency variants and enables accurate allele identification. The confidence gained from such an analysis is largely due to the strength of the signal generated by the target gene, such as 12S rRNA, making it particularly sound for targeted sequencing applications (Woo et al., 2023). While read length has an inherent limit due to the chemistry of Illumina’s sequencing method, Illumina provides a great compromise of accuracy, throughput, and low-end cost that together positions its technology as highly suitable for use in 12S rRNA sequencing workflows (Woo et al., 2023).

Due to the acquisition of whole gene-spanning reads in a single sequence, long-read sequencing technologies like PacBio and ONT have significant advantages for analysing 12S rRNA genes (Cahyadi et al., 2020). Because of this extensive coverage, time-consuming assembly steps like merging overlapping reads, a necessity in Illumina workflows, are off the table. In particular, long-read sequencing is well suited for resolving structural variants or guanine-cytosine-rich (GC-rich) or repetitive regions of the 12S rRNA gene, as many short-read platforms often struggle to achieve adequate mapping in these regions (Wenger et al., 2019). In addition, long read sequencing can mitigate the biases in library preparation steps (for example, shearing and PCR amplification) that are commonly encountered in Illumina workflows (Bohmann et al., 2022). Historically, long-read technologies like ONT exhibit greater base-calling errors when compared to Illumina (Ma et al., 2019; Wick et al., 2023) though emerging technologies such as PacBio HiFi sequencing have brought this gap to a narrow. The long reads provided by PacBio HiFi now match the high-quality Phred scores of Illumina’s short reads, in addition to greater read length and accuracy.

The benefits of long-read sequencing in 12S rRNA sequencing are unequivocal for applications that require full-gene resolution (Zhou et al., 2023), such as species identification, genealogical analysis, or mitochondrial heteroplasmy detection. Long-read technologies afford full coverage of the target region and therefore contribute to the reduction of ambiguity and increase confidence in downstream analyses. Although short-read platforms are a cost-effective solution for high-throughput and targeted applications, long-read sequencing is indispensable for acquiring nuanced and complete sequence information for the 12S rRNA gene.

Both short- and long-read sequencing technologies have unique advantages for 12S rRNA sequencing. Illumina is the best option with respect to accuracy, cost efficiency, and high throughput capability, making it the best option for monogenic assays and identifying single variant genes. On the flip side, long-read technologies such as PacBio and ONT are needed for complete analyses requiring full-gene resolution and structural information and thus represent an evolution of meta-analysis capabilities within bioinformatics data analysis.

Figure 2: The streamlined workflow for molecular halal verification through mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

NGS=Next Generation Sequencing; PCR=Polymerase Chain Reaction; TGS=Third Generation Sequencing