Volume 12, Issue 4 (December 2025)

J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025, 12(4): 293-300 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: Not applicable

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Putri N, Darmasiwi S. Characterization of Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substances from Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated during Spontaneous Fermentation of Shimeji Mushrooms (Hypsizygus sp.). J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2025; 12 (4) :293-300

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1378-en.html

URL: http://jfqhc.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-1378-en.html

Faculty of Biology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl Teknika Selatan, Sekip Utara Yogyakarta 52281, Indonesia , saridarma@ugm.ac.id

Full-Text [PDF 608 kb]

(90 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (118 Views)

Full-Text: (7 Views)

Characterization of Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substances from Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated during Spontaneous Fermentation of Shimeji Mushrooms (Hypsizygus sp.)

N.A. Putri, S. Darmasiwi *

Faculty of Biology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl Teknika Selatan, Sekip Utara Yogyakarta 52281, Indonesia

HIGHLIGHTS

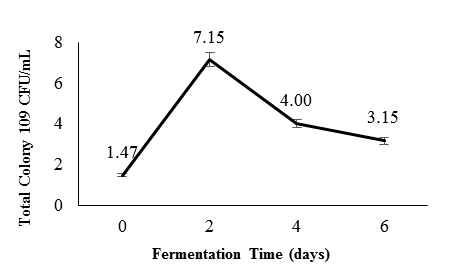

Figure 2: Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) population during the fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

Table 1: Characterization of selected lactic acid bacteria isolates from spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

N.A. Putri, S. Darmasiwi *

Faculty of Biology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl Teknika Selatan, Sekip Utara Yogyakarta 52281, Indonesia

- Hypsizygus sp. fermentation produced bacteriocins-like inhibitory substance from the powerful Lactic Acid Bacteria strains ISL-2A and ISL-4G, which inhibited Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.

- Bacteriocins-like inhibitory substance remained stable at pH 3–7 and up to 80 °C but lost sensitivity to proteolytic enzymes.

- Bacteriocins-like inhibitory substance showed potential as natural antimicrobials for food preservation.

| Article type Original article |

ABSTRACT Background: Spontaneous is an effective method to enhance the bioactivity and stability of foods through the action of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), the dominant microbes in this fermentation which generate antimicrobial metabolites, while also serving as a form of biological preservation. Hypsizygus sp., an edible mushroom valued for its high nutritional value, is highly perisable and benefits from biological preservation strategies. This study investigated LAB isolated from spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp. and characterized their bacteriocin-like inhibitory activity. Methods: Spontaneous fermentation was performed on Hypsizygus sp. using 2% NaCl, 1% sucrose, 3% chili pepper, and 2% garlic then incubated for 6 days at 27±1 °C. LAB were isolated on days 0, 2nd, 4th, and 6th using de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe agar (MRSA) medium, and characterized through colony and cell morphology, catalase activity, carbohydrate fermentation, and tolerance to salt and temperature. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances activity and stability were evaluated for antibacterial activity and stability across temperature, pH, and proteolytic enzyme treatment. Statistical analysis used two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post-hoc test (p<0.05). Results: Four isolates exhibited promising traits, with ISL-2A and ISL-4G—identified as belonging to the genus Lactobacillus—demonstrating the highest antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. The bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances produced were stable across a pH range of 3.0–7.0 and temperatures up to 80 °C, but were inactivated by proteolytic enzyme. Conclusion: These findings underscore the potential of LABs derived from fermented Hypsizygus sp. as natural antimicrobials and biopreservatives for food. © 2025, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences. This is an open access article under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |

|

| Keywords Anti-Bacterial Agents Bacteriocins Fermentation Food Preservation |

||

| Article history Received: 09 Jun 2025 Revised: 01 Dec 2025 Accepted: 02 Dec 2025 |

||

| Abbreviations CFU=Colony Forming Unit LAB=Lactic Acid Bacteria MRSA=de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe Agar rpm=revolutions per minute TPC=Total Plate Count |

To cite: Putri N.A., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Characterization of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from lactic acid bacteria isolated during spontaneous fermentation of shimeji mushrooms (Hypsizygus sp.). Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control. 12: 293-300.

Introduction

Introduction

Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) are widely recognized for their critical roles in food preservation, fermentation, and health. These Gram-positive, non-spore-forming, catalase-negative microorganisms—typically rod- or cocci-shaped—are known for their ability to ferment carbohydrates into lactic acid and produce antimicrobial metabolites, such as organic acids, CO₂, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins.

Among potential fermentation substrates, edible mushrooms like shimeji (Hypsizygus sp.) stand out due to their rich nutritional profile and diverse bioactive compounds. These mushrooms offer antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties, with studies reporting health benefits including reduced blood pressure, lower cholesterol, and protection against certain cancers (Monira et al., 2012; Skrzypczak et al., 2020). Shimeji extracts have shown inhibitory effects against Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli (Chowdury et al., 2015).

Due to their high content of polysaccharides, proteins, vitamins, and phenolic compounds, Hypsizygus sp. also provides a favorable environment for the growth of LAB, which can further enhance preservation and functional value through bacteriocin production. However, the high moisture and enzymatic activity of mushrooms make them prone to rapid spoilage, necessitating effective, natural preservation strategies (Baek et al., 2017).

Bacteriocins, ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by LAB, exhibit selective activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Pérez-Ramos et al., 2021). Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics, they target pathogens without harming beneficial microbiota (Zacharof and Lovitt, 2012). Some, like plantaricin from Lactobacillus spp., disrupt bacterial membranes by forming pores—causing membrane collapse and rapid cell death (Ahmad et al., 2017). Their safety for eukaryotic cells, along with their heat and pH stability, makes them attractive as both food biopreservatives and alternatives to conventional antibiotics (Cotter et al., 2013).

Spontaneous fermentation, which occurs without the addition of starter cultures, relies on the natural microflora present in raw materials and their surrounding environment. This method is thought to be good for isolating LAB strains that are well suited to the specific biochemical conditions of the substrate (Szutowska and Gwiazdowska, 2021). In substrates such as mushrooms, LABs play a central role by outcompeting undesirable microbes and producing antimicrobial metabolites like lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins (Skrzypczak et al., 2020).

Spontaneous fermentation tends to support the development of complex, diverse microbial communities, increasing the chances of discovering novel LAB strains with strong bacteriocin-producing capabilities (Dahunsi et al., 2022). These LABs often exhibit higher metabolic competitiveness and resilience, enhancing their ability to survive and function effectively in dynamic fermentation environments. Additionally, spontaneous fermentation does not require the preparation of specialized inocula, simplifying the process while promoting a natural, adaptive selection of beneficial microorganisms (Soorsesh et al., 2023). This microbial diversity can be a rich source of biopreservative agents with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, especially for perishable substrates like mushrooms.

Despite the promising attributes of LAB, research on bacteriocin production during the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus mushrooms remains limited. The study aimed to isolate and characterize LAB from the spontaneous fermentation of shimeji mushrooms and evaluate the production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances. Since the focus of this study was on preliminary biochemical characterization rather than molecular identification of LAB, and only crude supernatants were examined, the reported activity may reflect the combined effects of bacteriocins and other antimicrobial metabolites, namely bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances. Additionally, efforts should be made to purify the bacteriocins using techniques such as ammonium sulfate precipitation, ultrafiltration, or chromatographic separation to isolate individual bacteriocin.

Materials and methods

Hypsizygus sp. spontaneous fermentation

Fresh Hypsizygus sp. mushrooms and other raw materials were bought from a local market in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. About 150 g of mushrooms were washed in sterile warm water for pre-treatment of spontaneous fermentation. The mushrooms were cut into small pieces, and NaCl (2%, w/v) (GRM853, HiMedia, India) and sucrose (1%, w/v) (M576, HiMedia, India) were added to create osmotic conditions similar to traditional fermentation. The mixture was then left to allow water to be released from the mushrooms through processing osmosis (Jabłońska-Ryś et al., 2019). The mushrooms were then placed in a sterile 300 ml glass jar and incubated at room temperature for six days.

Isolation and selection of LAB

The selection of LAB isolates was carried out by taking a 10 g sample of the submerged fungus, followed by homogenization using a vortex (GEMMY, Taiwan) for 1 min. About 1 ml of the suspension was taken for serial dilution in physiological saline, and then about 100 µl of each dilution was transferred to a Petri dish containing prepared Plate Count Agar (PCA) (M091, HiMedia, India) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to determine the Total Plate Count (TPC). In addition, MRSA (GM641, HiMedia, India) supplemented with CaCO₃ (102066, Merck, Germany) was inoculated by spreading and incubated at 37 ℃for 48 h for LAB isolation. After incubation, colonies were taken and re-inoculated onto sterile MRSA, and the procedure was repeated twice to ensure the purity of the isolates. Purity was further confirmed by consistent colony morphology on repeated subculturing and by phenotypic characterization showing Gram-positive, catalase-negative traits typical of LAB. Although molecular (PCR-based) identification was not performed, these classical microbiological approaches were used for confirming LAB purity in preliminary studies. Isolation of LAB was carried out on day 0, day 2, day 4, and day 6 of fermentation. Each day, 10 isolates were obtained, colonies with typical LAB morphology (small, round, white to cream) were initially selected, and among them, those showing the largest clear zones on MRSA medium were chosen for further analysis (Chen et al., 2006; Skrzypczak et al., 2020).

Characterization of colony morphology and cell morphology

The characterization of colony morphology was conducted by observing LAB isolates grown on MRSA (GM641, HiMedia, India) medium after incubation for 24–48 h at 30 °C (Goa et al., 2022)

LAB catalase test

The test is conducted by dropping a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution (OneMed, Indonesia) onto a glass slide that has been inoculated with a single colony of bacteria from a 24-h culture (Goa et al., 2022)

LAB growth at various temperatures

Selected isolates were grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth (MV369, HiMedia, India) and incubated at temperatures of 10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, colony growth was observed (Goa et al., 2022).

LAB growth at various NaCl concentrations

The selected isolate was grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth (MV369, HiMedia, India) with the addition of NaCl (GRM853, HiMedia, India) at concentrations of 2%, 4%, and 6.5% and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, colony growth was observed (Goa et al., 2022).

The ability of LABs to produce gas from glucose

Pure isolates of LAB were inoculated into 10 ml of MRS HiVEG™ Broth containing inverted Durham tubes, then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h (Goa et al., 2022).

Production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

The strain was grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, the broth was centrifuged (Hettich, Germany) at 5,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 10 min at 4 °C, and the cells were separated. Cell-free supernatant was used as crude bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Antimicrobial activity test

The antimicrobial activity was tested against Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-negative) using the qualitative agar disc diffusion method. Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates (M173, HiMedia, India) were inoculated with bacterial suspensions standardized to McFarland 0.5 (~1×108 Colony Forming Unit (CFU)) (R092A, HiMedia, India) after incubation in nutrient broth (105450, Merck, Germany) at 37 °C for 18–24 h (Goa et al., 2022). The bacterial suspensions were adjusted using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 600 nm. Antimicrobial discs (MN 827 ATD, 484000, Macherey-Nagel, Germany) were soaked in Hypsizygus sp. bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances extract and placed on the inoculated Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. Inhibition zones (mm) were measured to assess antimicrobial activity.

Temperature stability test of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

Cell-free supernatant was taken in different test tubes and then treated at 4 °C, room temperature, 80 °C, and 121 °C. Room temperature treatment was used as a control. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances samples treated with temperature were tested for their antimicrobial activity (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

pH stability test of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

Cell-free supernatant of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances was taken in a test tube, and the pH value was measured and adjusted to pH 3, pH 7, and pH 10 individually, using dilute NaOH (106498, Merck, Germany) and HCl (109063, Merck, Germany) (0.1 M NaOH and 0.1 M HCl solution) (Veettil and Chitra, 2022). The samples were allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h, and the antimicrobial activity was tested (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances stability test under proteolytic enzymes

Cell-free supernatant was taken in a test tube and added with 1 mg/ml papain enzyme (Shaanxi Fonde Biotek Co., Ltd., China) dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (MB030, HiMedia, India) pH 7. The cell-free supernatant, which has been supplemented with protease enzymes, was subjected to temperature and pH treatments, and its antibacterial activity was re-evaluated (Wu et al., 2022).

Data analysis

Antibacterial activity was recorded, averaged, the standard deviation calculated, and statistically analyzed to compare treatments. Data were analysed using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, followed by two-way ANOVA and Sidak post-hoc comparisons in RStudio. Significance was accepted at p<0.05. Results are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD), and statistically distinct groups are denoted by different letters in the figures.

Results and discussion

Microbial population during spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

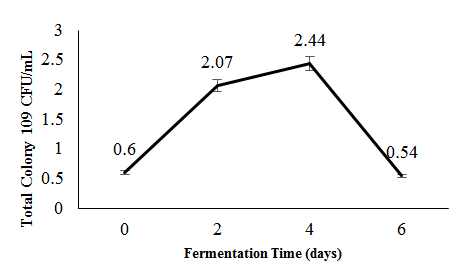

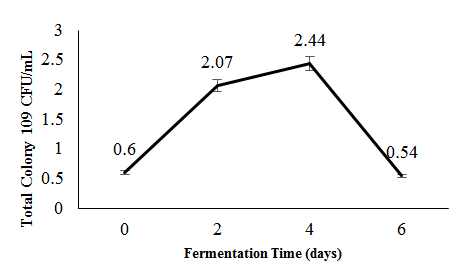

Microbial dynamics during fermentation were monitored using the TPC method, with samples collected on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. As shown in Figure 1, the initial TPC was 0.6×109 CFU/ml on day 0, increasing sharply to 2.07×109 CFU/ml on day 2 and peaking at 2.44×109 CFU/ml on day 4, before declining to 0.54×109 CFU/ml on day 6—likely due to nutrient depletion, accumulation of toxic metabolites, or the onset of the death phase (Tamang et al., 2016).

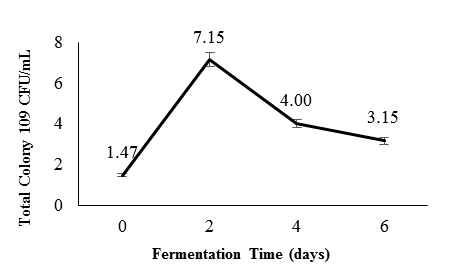

Similarly, Figure 2 shows an initial TPC of 1.47×109 CFU/ml on day 0, which rose to 7.15×109 CFU/ml by day 2, followed by decreases to 4×109 and 3.15×109 CFU/ml on days 4 and 6, respectively. LAB populations typically peak between days 2 and 4, then decline due to competition, nutrient exhaustion, and pH reduction. Species such as Leuconostoc mesenteroides are less acid-tolerant, whereas Lactobacillus plantarum withstands lower pH (McDonald et al., 1990; Zabat et al., 2018). The final decrease in LAB count is attributed to lactic acid accumulation, nutrient depletion, and autolysis (Li et al., 2017; Zimmerman and Ibrahim, 2021), marking the stabilization or completion phase of fermentation.

Among potential fermentation substrates, edible mushrooms like shimeji (Hypsizygus sp.) stand out due to their rich nutritional profile and diverse bioactive compounds. These mushrooms offer antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial properties, with studies reporting health benefits including reduced blood pressure, lower cholesterol, and protection against certain cancers (Monira et al., 2012; Skrzypczak et al., 2020). Shimeji extracts have shown inhibitory effects against Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli (Chowdury et al., 2015).

Due to their high content of polysaccharides, proteins, vitamins, and phenolic compounds, Hypsizygus sp. also provides a favorable environment for the growth of LAB, which can further enhance preservation and functional value through bacteriocin production. However, the high moisture and enzymatic activity of mushrooms make them prone to rapid spoilage, necessitating effective, natural preservation strategies (Baek et al., 2017).

Bacteriocins, ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by LAB, exhibit selective activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Pérez-Ramos et al., 2021). Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics, they target pathogens without harming beneficial microbiota (Zacharof and Lovitt, 2012). Some, like plantaricin from Lactobacillus spp., disrupt bacterial membranes by forming pores—causing membrane collapse and rapid cell death (Ahmad et al., 2017). Their safety for eukaryotic cells, along with their heat and pH stability, makes them attractive as both food biopreservatives and alternatives to conventional antibiotics (Cotter et al., 2013).

Spontaneous fermentation, which occurs without the addition of starter cultures, relies on the natural microflora present in raw materials and their surrounding environment. This method is thought to be good for isolating LAB strains that are well suited to the specific biochemical conditions of the substrate (Szutowska and Gwiazdowska, 2021). In substrates such as mushrooms, LABs play a central role by outcompeting undesirable microbes and producing antimicrobial metabolites like lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins (Skrzypczak et al., 2020).

Spontaneous fermentation tends to support the development of complex, diverse microbial communities, increasing the chances of discovering novel LAB strains with strong bacteriocin-producing capabilities (Dahunsi et al., 2022). These LABs often exhibit higher metabolic competitiveness and resilience, enhancing their ability to survive and function effectively in dynamic fermentation environments. Additionally, spontaneous fermentation does not require the preparation of specialized inocula, simplifying the process while promoting a natural, adaptive selection of beneficial microorganisms (Soorsesh et al., 2023). This microbial diversity can be a rich source of biopreservative agents with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, especially for perishable substrates like mushrooms.

Despite the promising attributes of LAB, research on bacteriocin production during the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus mushrooms remains limited. The study aimed to isolate and characterize LAB from the spontaneous fermentation of shimeji mushrooms and evaluate the production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances. Since the focus of this study was on preliminary biochemical characterization rather than molecular identification of LAB, and only crude supernatants were examined, the reported activity may reflect the combined effects of bacteriocins and other antimicrobial metabolites, namely bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances. Additionally, efforts should be made to purify the bacteriocins using techniques such as ammonium sulfate precipitation, ultrafiltration, or chromatographic separation to isolate individual bacteriocin.

Materials and methods

Hypsizygus sp. spontaneous fermentation

Fresh Hypsizygus sp. mushrooms and other raw materials were bought from a local market in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. About 150 g of mushrooms were washed in sterile warm water for pre-treatment of spontaneous fermentation. The mushrooms were cut into small pieces, and NaCl (2%, w/v) (GRM853, HiMedia, India) and sucrose (1%, w/v) (M576, HiMedia, India) were added to create osmotic conditions similar to traditional fermentation. The mixture was then left to allow water to be released from the mushrooms through processing osmosis (Jabłońska-Ryś et al., 2019). The mushrooms were then placed in a sterile 300 ml glass jar and incubated at room temperature for six days.

Isolation and selection of LAB

The selection of LAB isolates was carried out by taking a 10 g sample of the submerged fungus, followed by homogenization using a vortex (GEMMY, Taiwan) for 1 min. About 1 ml of the suspension was taken for serial dilution in physiological saline, and then about 100 µl of each dilution was transferred to a Petri dish containing prepared Plate Count Agar (PCA) (M091, HiMedia, India) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to determine the Total Plate Count (TPC). In addition, MRSA (GM641, HiMedia, India) supplemented with CaCO₃ (102066, Merck, Germany) was inoculated by spreading and incubated at 37 ℃for 48 h for LAB isolation. After incubation, colonies were taken and re-inoculated onto sterile MRSA, and the procedure was repeated twice to ensure the purity of the isolates. Purity was further confirmed by consistent colony morphology on repeated subculturing and by phenotypic characterization showing Gram-positive, catalase-negative traits typical of LAB. Although molecular (PCR-based) identification was not performed, these classical microbiological approaches were used for confirming LAB purity in preliminary studies. Isolation of LAB was carried out on day 0, day 2, day 4, and day 6 of fermentation. Each day, 10 isolates were obtained, colonies with typical LAB morphology (small, round, white to cream) were initially selected, and among them, those showing the largest clear zones on MRSA medium were chosen for further analysis (Chen et al., 2006; Skrzypczak et al., 2020).

Characterization of colony morphology and cell morphology

The characterization of colony morphology was conducted by observing LAB isolates grown on MRSA (GM641, HiMedia, India) medium after incubation for 24–48 h at 30 °C (Goa et al., 2022)

LAB catalase test

The test is conducted by dropping a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution (OneMed, Indonesia) onto a glass slide that has been inoculated with a single colony of bacteria from a 24-h culture (Goa et al., 2022)

LAB growth at various temperatures

Selected isolates were grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth (MV369, HiMedia, India) and incubated at temperatures of 10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, colony growth was observed (Goa et al., 2022).

LAB growth at various NaCl concentrations

The selected isolate was grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth (MV369, HiMedia, India) with the addition of NaCl (GRM853, HiMedia, India) at concentrations of 2%, 4%, and 6.5% and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, colony growth was observed (Goa et al., 2022).

The ability of LABs to produce gas from glucose

Pure isolates of LAB were inoculated into 10 ml of MRS HiVEG™ Broth containing inverted Durham tubes, then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h (Goa et al., 2022).

Production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

The strain was grown in MRS HiVEG™ Broth at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, the broth was centrifuged (Hettich, Germany) at 5,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 10 min at 4 °C, and the cells were separated. Cell-free supernatant was used as crude bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Antimicrobial activity test

The antimicrobial activity was tested against Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-negative) using the qualitative agar disc diffusion method. Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates (M173, HiMedia, India) were inoculated with bacterial suspensions standardized to McFarland 0.5 (~1×108 Colony Forming Unit (CFU)) (R092A, HiMedia, India) after incubation in nutrient broth (105450, Merck, Germany) at 37 °C for 18–24 h (Goa et al., 2022). The bacterial suspensions were adjusted using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 600 nm. Antimicrobial discs (MN 827 ATD, 484000, Macherey-Nagel, Germany) were soaked in Hypsizygus sp. bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances extract and placed on the inoculated Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. Inhibition zones (mm) were measured to assess antimicrobial activity.

Temperature stability test of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

Cell-free supernatant was taken in different test tubes and then treated at 4 °C, room temperature, 80 °C, and 121 °C. Room temperature treatment was used as a control. Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances samples treated with temperature were tested for their antimicrobial activity (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

pH stability test of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

Cell-free supernatant of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances was taken in a test tube, and the pH value was measured and adjusted to pH 3, pH 7, and pH 10 individually, using dilute NaOH (106498, Merck, Germany) and HCl (109063, Merck, Germany) (0.1 M NaOH and 0.1 M HCl solution) (Veettil and Chitra, 2022). The samples were allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 h, and the antimicrobial activity was tested (Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances stability test under proteolytic enzymes

Cell-free supernatant was taken in a test tube and added with 1 mg/ml papain enzyme (Shaanxi Fonde Biotek Co., Ltd., China) dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (MB030, HiMedia, India) pH 7. The cell-free supernatant, which has been supplemented with protease enzymes, was subjected to temperature and pH treatments, and its antibacterial activity was re-evaluated (Wu et al., 2022).

Data analysis

Antibacterial activity was recorded, averaged, the standard deviation calculated, and statistically analyzed to compare treatments. Data were analysed using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, followed by two-way ANOVA and Sidak post-hoc comparisons in RStudio. Significance was accepted at p<0.05. Results are expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD), and statistically distinct groups are denoted by different letters in the figures.

Results and discussion

Microbial population during spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

Microbial dynamics during fermentation were monitored using the TPC method, with samples collected on days 0, 2, 4, and 6. As shown in Figure 1, the initial TPC was 0.6×109 CFU/ml on day 0, increasing sharply to 2.07×109 CFU/ml on day 2 and peaking at 2.44×109 CFU/ml on day 4, before declining to 0.54×109 CFU/ml on day 6—likely due to nutrient depletion, accumulation of toxic metabolites, or the onset of the death phase (Tamang et al., 2016).

Similarly, Figure 2 shows an initial TPC of 1.47×109 CFU/ml on day 0, which rose to 7.15×109 CFU/ml by day 2, followed by decreases to 4×109 and 3.15×109 CFU/ml on days 4 and 6, respectively. LAB populations typically peak between days 2 and 4, then decline due to competition, nutrient exhaustion, and pH reduction. Species such as Leuconostoc mesenteroides are less acid-tolerant, whereas Lactobacillus plantarum withstands lower pH (McDonald et al., 1990; Zabat et al., 2018). The final decrease in LAB count is attributed to lactic acid accumulation, nutrient depletion, and autolysis (Li et al., 2017; Zimmerman and Ibrahim, 2021), marking the stabilization or completion phase of fermentation.

Figure 1: Total microbial count during the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

This study also showed that spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp. produced more total LABs compared to fermentation with the addition of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Bifidobacterium sp. as starters, which showed around 10 8 CFU/ml in a fermentation period of around 1 week, as we reported previously (Maskuri et al., 2025; Winurati and Darmasiwi, 2025)

This study also showed that spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp. produced more total LABs compared to fermentation with the addition of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Bifidobacterium sp. as starters, which showed around 10 8 CFU/ml in a fermentation period of around 1 week, as we reported previously (Maskuri et al., 2025; Winurati and Darmasiwi, 2025)

Figure 2: Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) population during the fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

Isolation and selection of LAB from fermented Hypsizygus sp.

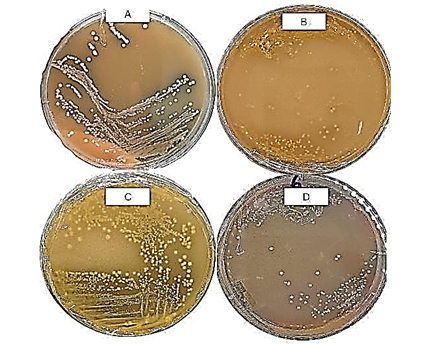

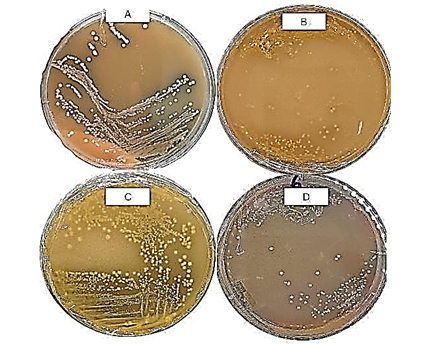

A total of 36 isolates were obtained from the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus (shimeji) mushrooms. All exhibited characteristic LAB morphology—round, convex colonies with smooth or slightly wavy edges and a white to cream color (Leska et al., 2022). The isolates showing the widest clear zones were reselected and labeled using the code “ISL,” followed by a number (fermentation day) and a letter (colony or plate ID). Based on this selection, isolates ISL-0E, ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E were identified as potential bacteriocin-producing LAB and sub cultured for further testing (Figure 3).

A total of 36 isolates were obtained from the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus (shimeji) mushrooms. All exhibited characteristic LAB morphology—round, convex colonies with smooth or slightly wavy edges and a white to cream color (Leska et al., 2022). The isolates showing the widest clear zones were reselected and labeled using the code “ISL,” followed by a number (fermentation day) and a letter (colony or plate ID). Based on this selection, isolates ISL-0E, ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E were identified as potential bacteriocin-producing LAB and sub cultured for further testing (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Isolates (A) ISL-0E (B) ISL-2A (C) ISL-4G (D) ISL-6E

ISL refers to the isolate code; the number indicates the sampling day, and the letter denotes the colony source.

Characterization of selected LAB isolates

Based on Table 1, all four isolates—ISL-0E, ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E—share several biochemical characteristics. All isolates tested negative in the catalase test, indicating the absence of the catalase enzyme. They were also able to grow at a wide range of temperatures, including 10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C, demonstrating adaptability to varying thermal conditions.

ISL refers to the isolate code; the number indicates the sampling day, and the letter denotes the colony source.

Characterization of selected LAB isolates

Based on Table 1, all four isolates—ISL-0E, ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E—share several biochemical characteristics. All isolates tested negative in the catalase test, indicating the absence of the catalase enzyme. They were also able to grow at a wide range of temperatures, including 10 °C, 25 °C, and 37 °C, demonstrating adaptability to varying thermal conditions.

Table 1: Characterization of selected lactic acid bacteria isolates from spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp.

| No | Isolate Codes | CAT | Gas Production | Growth at Various Temperatures | Growth in Various NaCl Concentrations | ||||

| 10 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 2% | 4% | 6.5% | ||||

| 1 | ISL-0E | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | ISL-2A | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | ISL-4G | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | ISL-6E | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

ISL refers to the isolate code; the number indicates the sampling day, and the letter denotes the colony source.

All isolates grew in media containing 2%, 4%, and 6.5% NaCl, indicating moderate halotolerance, though they differed in glucose fermentation ability: ISL-0E and ISL-2A fermented glucose, while ISL-4G and ISL-6E did not. These results show similar salt and temperature tolerance but distinct metabolic traits among isolates.

Isolated on the first fermentation day under aerobic, high-pH conditions, ISL-0E likely represents a Lactococcus strain, consistent with early-phase LAB dominance (Hou et al., 2023).

ISL-2A produced gas during glucose fermentation, suggesting heterofermentative metabolism typical of Lactobacillus brevis or Lactobacillus fermentum, which grow at 10–37 °C and tolerate up to 6.5% NaCl (Baek et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2025). In contrast, ISL-4G and ISL-6E, both rod-shaped, Gram-positive, and non–gas-producing, align with L. plantarum, a homo- or facultatively heterofermentative species known for salt tolerance and environmental adaptability (Holzapfel and Wood, 2014).

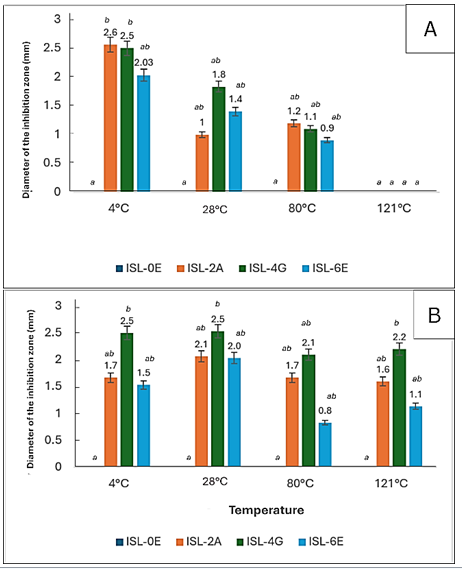

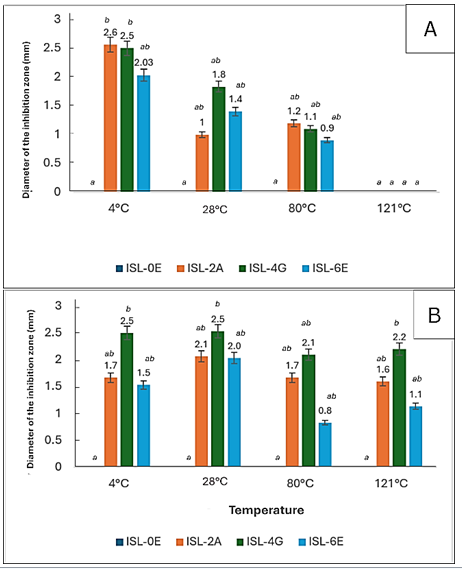

Characterization of the temperature stability of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

substances against E. coli decreased with increasing temperature. At 4 °C, ISL-2A and ISL-4G exhibited the highest activity, significantly greater than ISL-0E, while ISL-6E showed moderate but comparable inhibition. At 28 °C, inhibition zones of ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E decreased but remained higher than ISL-0E. Activity persisted at 80 °C (0.9–1.2 mm zones) but was completely lost at 121 °C, likely due to bacteriocin.

Figure 4A, exhibits the antibacterial activity of bacteriocin-like inhibitory denaturation (Mokoena, 2017). Overall, ISL-2A and ISL-4G were the most consistently active, especially at low temperatures.

Against S. aureus (Figure 4B), all isolates retained antibacterial activity even at 121 °C, indicating good thermal stability. ISL-4G consistently showed the strongest inhibition, followed by moderate activity from ISL-2A and ISL-6E, while ISL-0E remained inactive. Temperature had no significant effect on the overall antibacterial pattern of each isolate.

Figure 4: (A) Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from isolated lactic acid bacteria against Escherichia coli under varying temperatures (B) and against Staphylococcus aureus

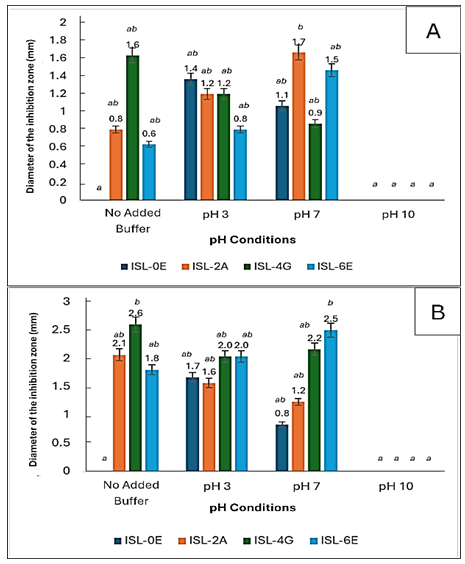

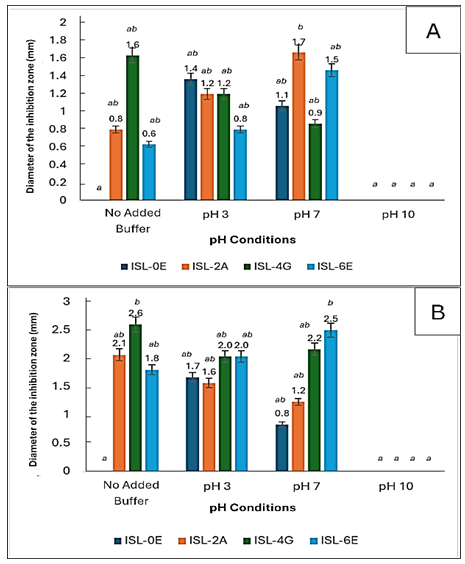

Characterization of the pH stability of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

As shown in Figure 5A, neutral pH (7) yielded the highest antibacterial activity for most isolates. ISL-0E was active at pH 3 and 7 but inactive at pH 9 and without buffer, indicating preference for acidic to neutral conditions. ISL-2A showed the greatest inhibition at pH 7 and remained moderately active at pH 3 and without buffer, while ISL-4G was most active without buffer but less effective at pH 3 and 7. ISL-6E showed similar patterns, with optimal activity at pH 7 and loss of activity at pH 9. Overall, bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances were most stable and active under neutral conditions, with reduced effectiveness in alkaline environments.

Figure 5: (A) Antimicrobial activity of the bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from isolated lactic acid bacteria against Escherichia coli under varying pH and against (B) Staphylococcus aureus under varying pH

Similarly, against S. aureus (Figure 5B), the highest activity occurred at pH 7, particularly for ISL-4G and ISL-6E. In contrast, at pH 10, inhibition was minimal or absent, likely due to denaturation of bacteriocin-like substances under strong alkaline conditions, confirming that neutral to slightly acidic pH favors bacteriocin stability and activity (Malik et al., 2016).

Table 2: Inhibition zone of the selected lactic acid bacteria bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances with the addition of protease enzyme

All isolates grew in media containing 2%, 4%, and 6.5% NaCl, indicating moderate halotolerance, though they differed in glucose fermentation ability: ISL-0E and ISL-2A fermented glucose, while ISL-4G and ISL-6E did not. These results show similar salt and temperature tolerance but distinct metabolic traits among isolates.

Isolated on the first fermentation day under aerobic, high-pH conditions, ISL-0E likely represents a Lactococcus strain, consistent with early-phase LAB dominance (Hou et al., 2023).

ISL-2A produced gas during glucose fermentation, suggesting heterofermentative metabolism typical of Lactobacillus brevis or Lactobacillus fermentum, which grow at 10–37 °C and tolerate up to 6.5% NaCl (Baek et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2025). In contrast, ISL-4G and ISL-6E, both rod-shaped, Gram-positive, and non–gas-producing, align with L. plantarum, a homo- or facultatively heterofermentative species known for salt tolerance and environmental adaptability (Holzapfel and Wood, 2014).

Characterization of the temperature stability of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

substances against E. coli decreased with increasing temperature. At 4 °C, ISL-2A and ISL-4G exhibited the highest activity, significantly greater than ISL-0E, while ISL-6E showed moderate but comparable inhibition. At 28 °C, inhibition zones of ISL-2A, ISL-4G, and ISL-6E decreased but remained higher than ISL-0E. Activity persisted at 80 °C (0.9–1.2 mm zones) but was completely lost at 121 °C, likely due to bacteriocin.

Figure 4A, exhibits the antibacterial activity of bacteriocin-like inhibitory denaturation (Mokoena, 2017). Overall, ISL-2A and ISL-4G were the most consistently active, especially at low temperatures.

Against S. aureus (Figure 4B), all isolates retained antibacterial activity even at 121 °C, indicating good thermal stability. ISL-4G consistently showed the strongest inhibition, followed by moderate activity from ISL-2A and ISL-6E, while ISL-0E remained inactive. Temperature had no significant effect on the overall antibacterial pattern of each isolate.

Figure 4: (A) Antimicrobial activity of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from isolated lactic acid bacteria against Escherichia coli under varying temperatures (B) and against Staphylococcus aureus

Characterization of the pH stability of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances

As shown in Figure 5A, neutral pH (7) yielded the highest antibacterial activity for most isolates. ISL-0E was active at pH 3 and 7 but inactive at pH 9 and without buffer, indicating preference for acidic to neutral conditions. ISL-2A showed the greatest inhibition at pH 7 and remained moderately active at pH 3 and without buffer, while ISL-4G was most active without buffer but less effective at pH 3 and 7. ISL-6E showed similar patterns, with optimal activity at pH 7 and loss of activity at pH 9. Overall, bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances were most stable and active under neutral conditions, with reduced effectiveness in alkaline environments.

Figure 5: (A) Antimicrobial activity of the bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances from isolated lactic acid bacteria against Escherichia coli under varying pH and against (B) Staphylococcus aureus under varying pH

Similarly, against S. aureus (Figure 5B), the highest activity occurred at pH 7, particularly for ISL-4G and ISL-6E. In contrast, at pH 10, inhibition was minimal or absent, likely due to denaturation of bacteriocin-like substances under strong alkaline conditions, confirming that neutral to slightly acidic pH favors bacteriocin stability and activity (Malik et al., 2016).

Table 2: Inhibition zone of the selected lactic acid bacteria bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances with the addition of protease enzyme

| Bacteriocin | Temperature Variations + Protease (Papain) | pH Variations + Protease (Papain) |

||||||

| 4 °C | 28 °C | 80 °C | 121 °C | No Added Buffer | pH 3 | pH 7 | pH 10 | |

| ISL-0E | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ISL-2A | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ISL-4G | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ISL-6E | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

ISL refers to the isolate code; the number indicates the sampling day, and the letter denotes the colony source.

(-) = No clear zones appeared.

Characterization of the bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances stability under proteolytic enzymes

Based on Table 2, no inhibition zones were observed after protease treatment, indicating that antibacterial activity was lost and the active compounds were proteinaceous, as they were degraded by proteolytic enzymes (Mótyán et al., 2013; Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Biochemical characterization showed a correlation between bacterial traits and bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance properties. ISL-0E, a catalase-negative, homofermentative strain tolerant to 6.5% NaCl and 10–37 °C, exhibited Lactococcus characteristics and likely produced class II bacteriocins (Ahmad et al., 2017). Although thermolabile, its enzyme sensitivity and pH-dependent activity align with class II traits. This agrees with Lactococcus spp. producing heat-sensitive bacteriocins such as lactococcin A and B, which lose activity above 70–80 °C (Héchard and Sahl, 2002; Sharma et al., 2022).

ISL-2A, a heterofermentative isolate tolerant to heat and salinity, likely belongs to L. brevis or L. fermentum and produces thermostable class II bacteriocins such as brevocin or fermenticin (Mokoena, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2017). ISL-4G and ISL-6E, rod-shaped and salt-tolerant with homo- or facultative heterofermentative metabolism, correspond to L. plantarum, known for producing plantaricin-type class II bacteriocins (Mokoena, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2017). All isolates lost antibacterial activity after protease treatment, confirming their proteinaceous nature (Mótyán et al., 2013).

Class II bacteriocins are generally thermostable, remaining active up to 121 °C, and stable within pH 4–8 (Cotter et al., 2013). The LAB isolates from this study tolerated high temperatures (up to 80 °C) and acidic pH, traits important for probiotic survival through the digestive tract (Zielińska et al., 2018). These bacteriocin-like substances show potential as natural preservatives against pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli, and Salmonella spp., and as starter cultures in traditional fermentation, enhancing product safety and functional value (Sharma et al., 2022).

However, the inhibitory zones observed were relatively unstable and enzyme-sensitive, indicating the need for optimization. Bacteriocin production is influenced by growth phase, medium composition, and pH regulation (Sidooski et al., 2019). Optimal production typically occurs during the exponential phase and can be enhanced by supplementing carbon and nitrogen sources. Glucose supports higher bacteriocin yields, though excess can inhibit growth, while pH control prevents excessive acid accumulation (Guerra et al., 2014; Sidooski et al., 2019). Agitation during fermentation also enhances production by improving nutrient distribution and pH stability (Guerra, 2014).

To improve stability against proteases, encapsulation techniques—such as using liposomes, alginate beads, or biodegradable polymers—can protect bacteriocins and allow controlled release. Encapsulated nisin, for example, maintained activity across temperature and pH variations (Eghbal et al., 2022). This approach enhances bacteriocin effectiveness for food preservation and potential probiotic applications. However, the present study did not analyze the molecular weight or amino acid composition of the active compounds. Future research should include these analyses, along with membrane-disruption or mode-of-action studies, to achieve a more complete characterization of the bacteriocins. Furthermore, future studies should include molecular identification using 16S rRNA sequencing to confirm the taxonomic position of the isolates at the species level and establish a stronger link between isolate identity and bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance production.

Conclusion

Isolate ISL-0E (Lactococcus spp.) produced a thermolabile class II bacteriocin stable under acidic to neutral pH but sensitive to proteolytic enzymes. Isolate ISL-2A, likely L. brevis or L. fermentum, produced a thermostable class II bacteriocin with similar pH tolerance and enzyme sensitivity. Isolates ISL-4G and ISL-6E, also presumed Lactobacillus species, produced highly thermostable bacteriocins that retained activity even after autoclaving at 121 °C, consistent with class II characteristics. The bacteriocin obtained from the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp. mushrooms was stable at acidic to neutral pH and at temperatures up to 80 °C but was degraded by proteases, suggesting limited structural protection. Nevertheless, this study did not determine the molecular weight or amino acid composition of the active compounds; future studies should include these analyses and explore their mechanisms of action for more complete characterization.

Author contributions

N.A.P. collected and analyzed data and wrote the first manuscript draft; S.D. developed the research concept, provided resource support for the collection of data, wrote the manuscript draft, and provided critical comments on the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to Wannisa Raksamat (Kanchanabhishek Institute of Medical and Public Health Technology Thailand) for her input on this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

References

Ahmad V., Khan M.S., Jamal Q.M.S., Alzohairy M.A., Al Karaawi M.A., Siddiqui M.U. (2017). Antimicrobial potential of bacteriocins: in therapy, agriculture and food preservation. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 49: 1–11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.08.016]

Baek Y.C., Kim M.S., Reddy K.E., Oh Y.K., Jung Y.H., Yeo J.M., Choi H. (2017). Rumen fermentation and digestibility of spent mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) substrate inoculated with Lactobacillus brevis for Hanwoo steers. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias. 30: 267–277. [DOI: 10.17533/udea.rccp.v30n4a02].

Chen Y.S., Yanagida F., Hsu J.S. (2006). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from dochi (fermented black beans), a traditional fermented food in Taiwan. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 43: 229–235. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01922.x]

Chowdhury M., Kubra K., Ahmed S. (2015). Screening of antimicrobial, antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds of some edible mushrooms cultivated in Bangladesh. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 14: 8. [DOI: 10.1186/s12941-015-0073-7]

Cotter P.D., Ross R.P., Hill C. (2013). Bacteriocins: a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 11: 95–105. [DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2937]

Dahunsi A.T., Dahunsi S.O., Ajayeoba T.A. (2022). Co-occurrence of Lactobacillus species during fermentation of African indigenous foods: impact on food safety and shelf life extension. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 684730. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.684730]

Eghbal N., Liao W., Dumas E., Azabou S., Dantigny P., Gharsallaoui A. (2022). Microencapsulation of natural food antimicrobials: methods and applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 12: 83837. [DOI: 10.3390/app12083837]

Goa T., Beyene G., Mekonnen M., Gorems K. (2022). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from fermented milk produced in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia, and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against selected pathogenic bacteria. International Journal of Food Science. 2022: 2076021. [DOI: 10.1155/2022/2076021]

Guerra N.P. (2014). Modeling the batch bacteriocin production system by lactic acid bacteria by using modified three-dimensional Lotka–Volterra equations. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 88: 115–130. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bej.2014.04.010]

Héchard Y., Sahl H.G. (2002). Mode of action of modified and unmodified bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimie. 84: 545–557. [DOI: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01400-1]

Hou M., Wang Z., Sun L., Jia Y., Wang S., Cai Y. (2023). Characteristics of lactic acid bacteria, microbial community and fermentation dynamics of native grass silage prepared in Inner Mongolian Plateau. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1072140. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1072140]

Jabłońska-Ryś E., Skrzypczak K., Sławińska A., Radzki W., Gustaw W. (2019). Lactic acid fermentation of edible mushrooms: tradition, technology, current state of research: a review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 18: 655–669. [DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12437]

Leska A., Nowak A., Motyl I. (2022). Isolation and some basic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) environment—a preliminary study. Agriculture. 12: 1562. [DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12101562]

Li Q., Kang J., Ma Z., Li X., Liu L., Hu X. (2017). Microbial succession and metabolite changes during traditional serofluid dish fermentation. LWT—Food Science and Technology. 84: 771–779. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.06.046]

Malik E., Dennison S.R., Harris F., Phoenix D.A. (2016). pH dependent antimicrobial peptides and proteins, their mechanisms of action and potential as therapeutic agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 9: 67. [DOI: 10.3390/ph9040067]

Maskuri H.A., Aramsirirujiwet Y., Kimkong I., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Biopreservation potential of shimeji (Hypsizygus sp.) mushroom fermented with Bifidobacterium sp. InaCC B723. Biosaintifika: Journal of Biology and Biology Education. 17: 169–178. [DOI: 10.15294/biosaintifika.v17i1.4964]

McDonald L.C., Fleming H.P., Hassan, H.M. (1990). Acid tolerance of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 56: 2120-2124. [DOI: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990]

Mokoena M.P. (2017). Lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins: classification, biosynthesis, and applications against uropathogens: a minireview. Molecules. 22: 1255. [DOI: 10.3390/molecules22081255]

Monira S., Haque A., Muhit M., Sarker N.C., Alam A., Rahman A., Khondkar P. (2012). Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of Hypsizygus tessulatus cultivated in Bangladesh. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants. 6: 300–308. [DOI: 10.3923/rjmp.2012.300.308]

Mótyán J., Tóth F., Tőzsér J. (2013). Research applications of proteolytic enzymes in molecular biology. Biomolecules. 3: 923–942. [DOI: 10.3390/biom3040923]

Pérez-Ramos A., Madi-Moussa D., Coucheney F., Drider D. (2021). Current knowledge of the mode of action and immunity mechanisms of LAB bacteriocins. Microorganisms. 9: 2107. [DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms9102107]

Sharma B.R., Halami P.M., Tamang J.P. (2022). Novel pathways in bacteriocin synthesis by lactic acid bacteria with special reference to ethnic fermented foods. Food Science and Biotechnology. 31: 1–16. [DOI: 10.1007/s10068-021-00986-w]

Sidooski T., Brandelli A., Bertoli S.L., Souza C.K. de, Carvalho L.F. de. (2019). Physical and nutritional conditions for optimized production of bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria—a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59: 2839–2849. [DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1474852]

Soorsesh M., Willing B.P., Bourrie B.C. (2023). Opportunities and challenges of understanding community assembly in spontaneous food fermentation. Foods. 12: 673. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12030673]

Skrzypczak K., Gustaw K., Jabłońska E., Sławińska A., Gustaw W., Winiarczyk S. (2020). Spontaneously fermented fruiting bodies of Agaricus bisporus as a valuable source of new isolates of lactic acid bacteria with functional potential. Foods. 9: 1631. [DOI: 10.3390/foods9111569]

Szutowska J., Gwiazdowska D. (2021). Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria obtained from fermented curly kale juice. Archives of Microbiology. 203: 975–988. [DOI: 10.1007/s00203-020-02063-3]

Tamang J.P., Shin D.H., Jung S.J., Chae S.W. (2016). Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods. Food Microbiology. 57: 578–590. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.001]

Udhayashree N., Senbagam D., Senthilkumar B., Nithya K., Gurusamy R. (2012). Production of bacteriocins and their application in food products. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2: S406–S410. [DOI: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60215-3]

Veettil V.N., Chitra V. (2022). Optimization of bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus plantarum using response surface methodology. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 68: 105–110. [DOI: 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.6.16]

Winurati A.K., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Microbiological and chemical profiling of lactofermented shimeji mushroom (Hypsizygus sp.) pickle juice using Lactobacillus bulgaricus as a starter culture. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 14: 11136. [DOI: 10.55251/jmbfs.11136]

Wu D., Dai M., Shi Y., Zhou Q., Li P., Gu Q. (2022). Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by a strain of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ZFM216. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1041369. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1050807]

Zacharof M.P., Lovitt R.W. (2012). Bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria: a review article. APCBEE Procedia. 2: 50–56. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1041369]

Wei G., Wang D., Wang T., Wang G., Chai Y., Li Y., Mei M., Wang H., Huang A. (2025). Probiotic potential and safety properties of Limosilactobacillus fermentum A51 with high exopolysaccharide production. Frontiers in Microbiology. 16: 1498352. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1498352]

Zabat M.A., Sano W.H., Wurster J.I., Cabral D.J., Belenky P. (2018). Microbial community analysis of sauerkraut fermentation reveals a stable and rapidly established community. Foods. 7: 77. [DOI: 10.3390/foods7050077]

Zielińska D., Kolozyn-Krajewska D., Laranjo M. (2018). Food-origin lactic acid bacteria may exhibit probiotic properties: a review. BioMed Research International. 2018: 5063185. [DOI: 10.1155/2018/5063185]

Zimmerman T., Ibrahim S.A. (2021). Autolysis and cell death is affected by pH in Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 20016 cells. Foods. 10: 1026. [DOI: 10.3390/foods10051026]

(-) = No clear zones appeared.

Characterization of the bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances stability under proteolytic enzymes

Based on Table 2, no inhibition zones were observed after protease treatment, indicating that antibacterial activity was lost and the active compounds were proteinaceous, as they were degraded by proteolytic enzymes (Mótyán et al., 2013; Udhayashree et al., 2012).

Biochemical characterization showed a correlation between bacterial traits and bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance properties. ISL-0E, a catalase-negative, homofermentative strain tolerant to 6.5% NaCl and 10–37 °C, exhibited Lactococcus characteristics and likely produced class II bacteriocins (Ahmad et al., 2017). Although thermolabile, its enzyme sensitivity and pH-dependent activity align with class II traits. This agrees with Lactococcus spp. producing heat-sensitive bacteriocins such as lactococcin A and B, which lose activity above 70–80 °C (Héchard and Sahl, 2002; Sharma et al., 2022).

ISL-2A, a heterofermentative isolate tolerant to heat and salinity, likely belongs to L. brevis or L. fermentum and produces thermostable class II bacteriocins such as brevocin or fermenticin (Mokoena, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2017). ISL-4G and ISL-6E, rod-shaped and salt-tolerant with homo- or facultative heterofermentative metabolism, correspond to L. plantarum, known for producing plantaricin-type class II bacteriocins (Mokoena, 2017; Ahmad et al., 2017). All isolates lost antibacterial activity after protease treatment, confirming their proteinaceous nature (Mótyán et al., 2013).

Class II bacteriocins are generally thermostable, remaining active up to 121 °C, and stable within pH 4–8 (Cotter et al., 2013). The LAB isolates from this study tolerated high temperatures (up to 80 °C) and acidic pH, traits important for probiotic survival through the digestive tract (Zielińska et al., 2018). These bacteriocin-like substances show potential as natural preservatives against pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli, and Salmonella spp., and as starter cultures in traditional fermentation, enhancing product safety and functional value (Sharma et al., 2022).

However, the inhibitory zones observed were relatively unstable and enzyme-sensitive, indicating the need for optimization. Bacteriocin production is influenced by growth phase, medium composition, and pH regulation (Sidooski et al., 2019). Optimal production typically occurs during the exponential phase and can be enhanced by supplementing carbon and nitrogen sources. Glucose supports higher bacteriocin yields, though excess can inhibit growth, while pH control prevents excessive acid accumulation (Guerra et al., 2014; Sidooski et al., 2019). Agitation during fermentation also enhances production by improving nutrient distribution and pH stability (Guerra, 2014).

To improve stability against proteases, encapsulation techniques—such as using liposomes, alginate beads, or biodegradable polymers—can protect bacteriocins and allow controlled release. Encapsulated nisin, for example, maintained activity across temperature and pH variations (Eghbal et al., 2022). This approach enhances bacteriocin effectiveness for food preservation and potential probiotic applications. However, the present study did not analyze the molecular weight or amino acid composition of the active compounds. Future research should include these analyses, along with membrane-disruption or mode-of-action studies, to achieve a more complete characterization of the bacteriocins. Furthermore, future studies should include molecular identification using 16S rRNA sequencing to confirm the taxonomic position of the isolates at the species level and establish a stronger link between isolate identity and bacteriocin-like inhibitory substance production.

Conclusion

Isolate ISL-0E (Lactococcus spp.) produced a thermolabile class II bacteriocin stable under acidic to neutral pH but sensitive to proteolytic enzymes. Isolate ISL-2A, likely L. brevis or L. fermentum, produced a thermostable class II bacteriocin with similar pH tolerance and enzyme sensitivity. Isolates ISL-4G and ISL-6E, also presumed Lactobacillus species, produced highly thermostable bacteriocins that retained activity even after autoclaving at 121 °C, consistent with class II characteristics. The bacteriocin obtained from the spontaneous fermentation of Hypsizygus sp. mushrooms was stable at acidic to neutral pH and at temperatures up to 80 °C but was degraded by proteases, suggesting limited structural protection. Nevertheless, this study did not determine the molecular weight or amino acid composition of the active compounds; future studies should include these analyses and explore their mechanisms of action for more complete characterization.

Author contributions

N.A.P. collected and analyzed data and wrote the first manuscript draft; S.D. developed the research concept, provided resource support for the collection of data, wrote the manuscript draft, and provided critical comments on the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to Wannisa Raksamat (Kanchanabhishek Institute of Medical and Public Health Technology Thailand) for her input on this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

References

Ahmad V., Khan M.S., Jamal Q.M.S., Alzohairy M.A., Al Karaawi M.A., Siddiqui M.U. (2017). Antimicrobial potential of bacteriocins: in therapy, agriculture and food preservation. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 49: 1–11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.08.016]

Baek Y.C., Kim M.S., Reddy K.E., Oh Y.K., Jung Y.H., Yeo J.M., Choi H. (2017). Rumen fermentation and digestibility of spent mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) substrate inoculated with Lactobacillus brevis for Hanwoo steers. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias. 30: 267–277. [DOI: 10.17533/udea.rccp.v30n4a02].

Chen Y.S., Yanagida F., Hsu J.S. (2006). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from dochi (fermented black beans), a traditional fermented food in Taiwan. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 43: 229–235. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01922.x]

Chowdhury M., Kubra K., Ahmed S. (2015). Screening of antimicrobial, antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds of some edible mushrooms cultivated in Bangladesh. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 14: 8. [DOI: 10.1186/s12941-015-0073-7]

Cotter P.D., Ross R.P., Hill C. (2013). Bacteriocins: a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 11: 95–105. [DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2937]

Dahunsi A.T., Dahunsi S.O., Ajayeoba T.A. (2022). Co-occurrence of Lactobacillus species during fermentation of African indigenous foods: impact on food safety and shelf life extension. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 684730. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.684730]

Eghbal N., Liao W., Dumas E., Azabou S., Dantigny P., Gharsallaoui A. (2022). Microencapsulation of natural food antimicrobials: methods and applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 12: 83837. [DOI: 10.3390/app12083837]

Goa T., Beyene G., Mekonnen M., Gorems K. (2022). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from fermented milk produced in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia, and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against selected pathogenic bacteria. International Journal of Food Science. 2022: 2076021. [DOI: 10.1155/2022/2076021]

Guerra N.P. (2014). Modeling the batch bacteriocin production system by lactic acid bacteria by using modified three-dimensional Lotka–Volterra equations. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 88: 115–130. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bej.2014.04.010]

Héchard Y., Sahl H.G. (2002). Mode of action of modified and unmodified bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimie. 84: 545–557. [DOI: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01400-1]

Hou M., Wang Z., Sun L., Jia Y., Wang S., Cai Y. (2023). Characteristics of lactic acid bacteria, microbial community and fermentation dynamics of native grass silage prepared in Inner Mongolian Plateau. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1072140. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1072140]

Jabłońska-Ryś E., Skrzypczak K., Sławińska A., Radzki W., Gustaw W. (2019). Lactic acid fermentation of edible mushrooms: tradition, technology, current state of research: a review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 18: 655–669. [DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12437]

Leska A., Nowak A., Motyl I. (2022). Isolation and some basic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) environment—a preliminary study. Agriculture. 12: 1562. [DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12101562]

Li Q., Kang J., Ma Z., Li X., Liu L., Hu X. (2017). Microbial succession and metabolite changes during traditional serofluid dish fermentation. LWT—Food Science and Technology. 84: 771–779. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.06.046]

Malik E., Dennison S.R., Harris F., Phoenix D.A. (2016). pH dependent antimicrobial peptides and proteins, their mechanisms of action and potential as therapeutic agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 9: 67. [DOI: 10.3390/ph9040067]

Maskuri H.A., Aramsirirujiwet Y., Kimkong I., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Biopreservation potential of shimeji (Hypsizygus sp.) mushroom fermented with Bifidobacterium sp. InaCC B723. Biosaintifika: Journal of Biology and Biology Education. 17: 169–178. [DOI: 10.15294/biosaintifika.v17i1.4964]

McDonald L.C., Fleming H.P., Hassan, H.M. (1990). Acid tolerance of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 56: 2120-2124. [DOI: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990]

Mokoena M.P. (2017). Lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins: classification, biosynthesis, and applications against uropathogens: a minireview. Molecules. 22: 1255. [DOI: 10.3390/molecules22081255]

Monira S., Haque A., Muhit M., Sarker N.C., Alam A., Rahman A., Khondkar P. (2012). Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of Hypsizygus tessulatus cultivated in Bangladesh. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants. 6: 300–308. [DOI: 10.3923/rjmp.2012.300.308]

Mótyán J., Tóth F., Tőzsér J. (2013). Research applications of proteolytic enzymes in molecular biology. Biomolecules. 3: 923–942. [DOI: 10.3390/biom3040923]

Pérez-Ramos A., Madi-Moussa D., Coucheney F., Drider D. (2021). Current knowledge of the mode of action and immunity mechanisms of LAB bacteriocins. Microorganisms. 9: 2107. [DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms9102107]

Sharma B.R., Halami P.M., Tamang J.P. (2022). Novel pathways in bacteriocin synthesis by lactic acid bacteria with special reference to ethnic fermented foods. Food Science and Biotechnology. 31: 1–16. [DOI: 10.1007/s10068-021-00986-w]

Sidooski T., Brandelli A., Bertoli S.L., Souza C.K. de, Carvalho L.F. de. (2019). Physical and nutritional conditions for optimized production of bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria—a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59: 2839–2849. [DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1474852]

Soorsesh M., Willing B.P., Bourrie B.C. (2023). Opportunities and challenges of understanding community assembly in spontaneous food fermentation. Foods. 12: 673. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12030673]

Skrzypczak K., Gustaw K., Jabłońska E., Sławińska A., Gustaw W., Winiarczyk S. (2020). Spontaneously fermented fruiting bodies of Agaricus bisporus as a valuable source of new isolates of lactic acid bacteria with functional potential. Foods. 9: 1631. [DOI: 10.3390/foods9111569]

Szutowska J., Gwiazdowska D. (2021). Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria obtained from fermented curly kale juice. Archives of Microbiology. 203: 975–988. [DOI: 10.1007/s00203-020-02063-3]

Tamang J.P., Shin D.H., Jung S.J., Chae S.W. (2016). Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods. Food Microbiology. 57: 578–590. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.001]

Udhayashree N., Senbagam D., Senthilkumar B., Nithya K., Gurusamy R. (2012). Production of bacteriocins and their application in food products. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2: S406–S410. [DOI: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60215-3]

Veettil V.N., Chitra V. (2022). Optimization of bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus plantarum using response surface methodology. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 68: 105–110. [DOI: 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.6.16]

Winurati A.K., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Microbiological and chemical profiling of lactofermented shimeji mushroom (Hypsizygus sp.) pickle juice using Lactobacillus bulgaricus as a starter culture. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 14: 11136. [DOI: 10.55251/jmbfs.11136]

Wu D., Dai M., Shi Y., Zhou Q., Li P., Gu Q. (2022). Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by a strain of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ZFM216. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1041369. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1050807]

Zacharof M.P., Lovitt R.W. (2012). Bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria: a review article. APCBEE Procedia. 2: 50–56. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1041369]

Wei G., Wang D., Wang T., Wang G., Chai Y., Li Y., Mei M., Wang H., Huang A. (2025). Probiotic potential and safety properties of Limosilactobacillus fermentum A51 with high exopolysaccharide production. Frontiers in Microbiology. 16: 1498352. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1498352]

Zabat M.A., Sano W.H., Wurster J.I., Cabral D.J., Belenky P. (2018). Microbial community analysis of sauerkraut fermentation reveals a stable and rapidly established community. Foods. 7: 77. [DOI: 10.3390/foods7050077]

Zielińska D., Kolozyn-Krajewska D., Laranjo M. (2018). Food-origin lactic acid bacteria may exhibit probiotic properties: a review. BioMed Research International. 2018: 5063185. [DOI: 10.1155/2018/5063185]

Zimmerman T., Ibrahim S.A. (2021). Autolysis and cell death is affected by pH in Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 20016 cells. Foods. 10: 1026. [DOI: 10.3390/foods10051026]

[*] Corresponding author (S. Darmasiwi)

Email: saridarma@ugm.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6179-5500

Email: saridarma@ugm.ac.id

Orchid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6179-5500

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Special

Received: 25/06/09 | Accepted: 25/12/02 | Published: 25/12/21

Received: 25/06/09 | Accepted: 25/12/02 | Published: 25/12/21

References

1. Ahmad V., Khan M.S., Jamal Q.M.S., Alzohairy M.A., Al Karaawi M.A., Siddiqui M.U. (2017). Antimicrobial potential of bacteriocins: in therapy, agriculture and food preservation. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 49: 1-11. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.08.016] [DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.08.016] [PMID]

2. Baek Y.C., Kim M.S., Reddy K.E., Oh Y.K., Jung Y.H., Yeo J.M., Choi H. (2017). Rumen fermentation and digestibility of spent mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) substrate inoculated with Lactobacillus brevis for Hanwoo steers. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias. 30: 267-277. [DOI: 10.17533/udea.rccp.v30n4a02]. [DOI:10.17533/udea.rccp.v30n4a02]

3. Chen Y.S., Yanagida F., Hsu J.S. (2006). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from dochi (fermented black beans), a traditional fermented food in Taiwan. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 43: 229-235. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01922.x] [DOI:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01922.x] [PMID]

4. Chowdhury M., Kubra K., Ahmed S. (2015). Screening of antimicrobial, antioxidant properties and bioactive compounds of some edible mushrooms cultivated in Bangladesh. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 14: 8. [DOI: 10.1186/s12941-015-0073-7] [DOI:10.1186/s12941-015-0067-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

5. Cotter P.D., Ross R.P., Hill C. (2013). Bacteriocins: a viable alternative to antibiotics? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 11: 95-105. [DOI: 10.1038/nrmicro2937] [DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2937] [PMID]

6. Dahunsi A.T., Dahunsi S.O., Ajayeoba T.A. (2022). Co-occurrence of Lactobacillus species during fermentation of African indigenous foods: impact on food safety and shelf life extension. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 684730. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.684730] [DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.684730] [PMID] [PMCID]

7. Eghbal N., Liao W., Dumas E., Azabou S., Dantigny P., Gharsallaoui A. (2022). Microencapsulation of natural food antimicrobials: methods and applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland). 12: 83837. [DOI: 10.3390/app12083837] [DOI:10.3390/app12083837]

8. Goa T., Beyene G., Mekonnen M., Gorems K. (2022). Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from fermented milk produced in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia, and evaluation of their antimicrobial activity against selected pathogenic bacteria. International Journal of Food Science. 2022: 2076021. [DOI: 10.1155/2022/2076021] [DOI:10.1155/2022/2076021] [PMID] [PMCID]

9. Guerra N.P. (2014). Modeling the batch bacteriocin production system by lactic acid bacteria by using modified three-dimensional Lotka-Volterra equations. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 88: 115-130. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bej.2014.04.010] [DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2014.04.010]

10. Héchard Y., Sahl H.G. (2002). Mode of action of modified and unmodified bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimie. 84: 545-557. [DOI: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01400-1] [DOI:10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01400-1] [PMID]

11. Hou M., Wang Z., Sun L., Jia Y., Wang S., Cai Y. (2023). Characteristics of lactic acid bacteria, microbial community and fermentation dynamics of native grass silage prepared in Inner Mongolian Plateau. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1072140. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1072140] [DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.1072140] [PMID] [PMCID]

12. Jabłońska-Ryś E., Skrzypczak K., Sławińska A., Radzki W., Gustaw W. (2019). Lactic acid fermentation of edible mushrooms: tradition, technology, current state of research: a review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 18: 655-669. [DOI: 10.1111/1541-4337.12437] [DOI:10.1111/1541-4337.12437] [PMID]

13. Leska A., Nowak A., Motyl I. (2022). Isolation and some basic characteristics of lactic acid bacteria from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) environment-a preliminary study. Agriculture. 12: 1562. [DOI: 10.3390/agriculture12101562] [DOI:10.3390/agriculture12101562]

14. Li Q., Kang J., Ma Z., Li X., Liu L., Hu X. (2017). Microbial succession and metabolite changes during traditional serofluid dish fermentation. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 84: 771-779. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.06.046] [DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2017.06.046]

15. Malik E., Dennison S.R., Harris F., Phoenix D.A. (2016). pH dependent antimicrobial peptides and proteins, their mechanisms of action and potential as therapeutic agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 9: 67. [DOI: 10.3390/ph9040067] [DOI:10.3390/ph9040067] [PMID] [PMCID]

16. Maskuri H.A., Aramsirirujiwet Y., Kimkong I., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Biopreservation potential of shimeji (Hypsizygus sp.) mushroom fermented with Bifidobacterium sp. InaCC B723. Biosaintifika: Journal of Biology and Biology Education. 17: 169-178. [DOI: 10.15294/biosaintifika.v17i1.4964] [DOI:10.15294/biosaintifika.v17i1.4964]

17. McDonald L.C., Fleming H.P., Hassan, H.M. (1990). Acid tolerance of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 56: 2120-2124. [DOI: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990] [DOI:10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990] [PMID] [PMCID]

18. Mokoena M.P. (2017). Lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins: classification, biosynthesis, and applications against uropathogens: a minireview. Molecules. 22: 1255. [DOI: 10.3390/molecules22081255] [DOI:10.3390/molecules22081255] [PMID] [PMCID]

19. Monira S., Haque A., Muhit M., Sarker N.C., Alam A., Rahman A., Khondkar P. (2012). Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic properties of Hypsizygus tessulatus cultivated in Bangladesh. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants. 6: 300-308. [DOI: 10.3923/rjmp.2012.300.308] [DOI:10.3923/rjmp.2012.300.308]

20. Mótyán J., Tóth F., Tőzsér J. (2013). Research applications of proteolytic enzymes in molecular biology. Biomolecules. 3: 923-942. [DOI: 10.3390/biom3040923] [DOI:10.3390/biom3040923] [PMID] [PMCID]

21. Pérez-Ramos A., Madi-Moussa D., Coucheney F., Drider D. (2021). Current knowledge of the mode of action and immunity mechanisms of LAB bacteriocins. Microorganisms. 9: 2107. [DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms9102107] [DOI:10.3390/microorganisms9102107] [PMID] [PMCID]

22. Sharma B.R., Halami P.M., Tamang J.P. (2022). Novel pathways in bacteriocin synthesis by lactic acid bacteria with special reference to ethnic fermented foods. Food Science and Biotechnology. 31: 1-16. [DOI: 10.1007/s10068-021-00986-w] [DOI:10.1007/s10068-021-00986-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

23. Sidooski T., Brandelli A., Bertoli S.L., Souza C.K. de, Carvalho L.F. de. (2019). Physical and nutritional conditions for optimized production of bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria-a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 59: 2839-2849. [DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1474852] [DOI:10.1080/10408398.2018.1474852] [PMID]

24. Soorsesh M., Willing B.P., Bourrie B.C. (2023). Opportunities and challenges of understanding community assembly in spontaneous food fermentation. Foods. 12: 673. [DOI: 10.3390/foods12030673] [DOI:10.3390/foods12030673] [PMID] [PMCID]

25. Skrzypczak K., Gustaw K., Jabłońska E., Sławińska A., Gustaw W., Winiarczyk S. (2020). Spontaneously fermented fruiting bodies of Agaricus bisporus as a valuable source of new isolates of lactic acid bacteria with functional potential. Foods. 9: 1631. [DOI: 10.3390/foods9111569] [DOI:10.3390/foods9111569] [PMID] [PMCID]

26. Szutowska J., Gwiazdowska D. (2021). Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria obtained from fermented curly kale juice. Archives of Microbiology. 203: 975-988. [DOI: 10.1007/s00203-020-02063-3] [DOI:10.1007/s00203-020-02095-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

27. Tamang J.P., Shin D.H., Jung S.J., Chae S.W. (2016). Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods. Food Microbiology. 57: 578-590. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.001] [DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2016.02.001] [PMID]

28. Udhayashree N., Senbagam D., Senthilkumar B., Nithya K., Gurusamy R. (2012). Production of bacteriocins and their application in food products. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2: S406-S410. [DOI: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60215-3] [DOI:10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60197-X]

29. Veettil V.N., Chitra V. (2022). Optimization of bacteriocin production by Lactobacillus plantarum using response surface methodology. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 68: 105-110. [DOI: 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.6.16] [DOI:10.14715/cmb/2022.68.6.16] [PMID]

30. Winurati A.K., Darmasiwi S. (2025). Microbiological and chemical profiling of lactofermented shimeji mushroom (Hypsizygus sp.) pickle juice using Lactobacillus bulgaricus as a starter culture. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 14: 11136. [DOI: 10.55251/jmbfs.11136] [DOI:10.55251/jmbfs.11136]

31. Wu D., Dai M., Shi Y., Zhou Q., Li P., Gu Q. (2022). Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by a strain of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus ZFM216. Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 1041369. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1050807] [DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.1050807] [PMID] [PMCID]

32. Zacharof M.P., Lovitt R.W. (2012). Bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria: a review article. APCBEE Procedia. 2: 50-56. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1041369] [DOI:10.1016/j.apcbee.2012.06.010]

33. Wei G., Wang D., Wang T., Wang G., Chai Y., Li Y., Mei M., Wang H., Huang A. (2025). Probiotic potential and safety properties of Limosilactobacillus fermentum A51 with high exopolysaccharide production. Frontiers in Microbiology. 16: 1498352. [DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1498352] [DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2025.1498352] [PMID] [PMCID]

34. Zabat M.A., Sano W.H., Wurster J.I., Cabral D.J., Belenky P. (2018). Microbial community analysis of sauerkraut fermentation reveals a stable and rapidly established community. Foods. 7: 77. [DOI: 10.3390/foods7050077] [DOI:10.3390/foods7050077] [PMID] [PMCID]